A spellbound Pat Mazza Jr. watched toy dinosaurs emerge from Dinoland’s Mold-A-Rama machine at the 1964 World’s Fair in Queens, and when he got one, he chomped off the still-warm head.

He was only 2, but the Dinoland exhibit started his “craze” for monsters and the good times turned him into a 1964 World’s Fair collector. He now has 12 toy dinosaurs, each purchased for under $50, and just holding them evokes the image of his first one and that unique smell of hot wax.

Pat Mazza Jr. plays with the various Dinoland Mold-A-Rama dinosaurs his father bought him in 1966. Credit: Pat Mazza

“People think that going back in time is impossible,” says Mazza, 62, a retired police officer from Massapequa. “That’s about the furthest thing from the truth.”

Collectors have kept alive the 1964 showcase of American technology and cultures of the world, spread on 646 acres at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens in Queens 60 years ago. Items have gone from trash to treasure, including first-day tickets and posters publicizing the fair. Anything created by someone famous commands big prices, such as $48,750 for Walt Disney’s table and chair set in General Electric exhibit, Progressland, showcasing the story of electricity.

Many souvenirs still survive with the 1964 World’s Fair brand. Its mascots — a boy and girl outfitted in the blue and orange colors of the fair — and its iconic symbol of the earth, the Unisphere, were on everything. Rain ponchos. Vinyl purses. Gold medallions. Pocket knives. Food picks. Charm bracelets.

Collector Tim Tomasini, 72, says his favorite find may be two ashtrays because they show the Unisphere with its fountains in color.

He displays many of his 25 or so items and 40 brochures around his Bayport home, a collection that was also featured at the Bayport-Blue Point Public Library about three years ago. Among his treasures are two glass banks from the Esso gas company, now known as Exxon; a wall plaque that shows scenes of New York City; and a figurine of a Vatican guard from the papal pavilion.

Tim Tomasini has two 1964 Wold's Fair ash trays showing the Unisphere. Credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

His parents, with seven kids in tow at the fair, could not afford to buy souvenirs, so Tomasini hunts for collectibles at auctions, estate sales and antique shops. “I’m actually preserving them from maybe ending up in a dumpster,” the collector says. “When we preserve artifacts from our past, we are preserving our nation’s heritage.”

I can escape back to 1964, when there were promises of undersea hotels and colonies on the moon and all these wonderful things.

-Bill Cotter, collector

For many, the memorabilia hark back to a time of space exploration, technological progress and a call for peace between nations.

“It’s a memory of a simpler time, when there was unbridled optimism,” says collector Bill Cotter, 72, a California retiree who was a Baldwin kid recycling soda bottles to pay for fair tickets. “The world we have today is real depressing in so many ways. I can escape back to 1964, when there were promises of undersea hotels and colonies on the moon and all these wonderful things.”

Tim Tomasini saved a World's Fair edition of Newsday. Credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

He began collecting after revisiting the old fairgrounds during a New York business trip, then advertising in newspapers his desire to buy 1964 memorabilia.

Cotter now runs World’s Fair info websites from his home in Granada Hills, California. He has badges, buttons and other free items from his childhood visits, along with 30,000 photos and a favorite find, the “Ave of Progress” sign that hung outside the General Electric pavilion.

But he got his most meaningful souvenir from the Egyptian pavilion as the fair was about to close in 1965: a wad of cotton.

He was 13, talking with an employee who looked downcast because she would be returning to Egypt, where women did not have many rights. When he wished her well, she pulled off some cotton from a wall display and gave it to him.

Cotter collects because the fair changed his life in several ways, he says. “You start realizing that people outside your little sphere of influence live in totally different worlds than you do.”

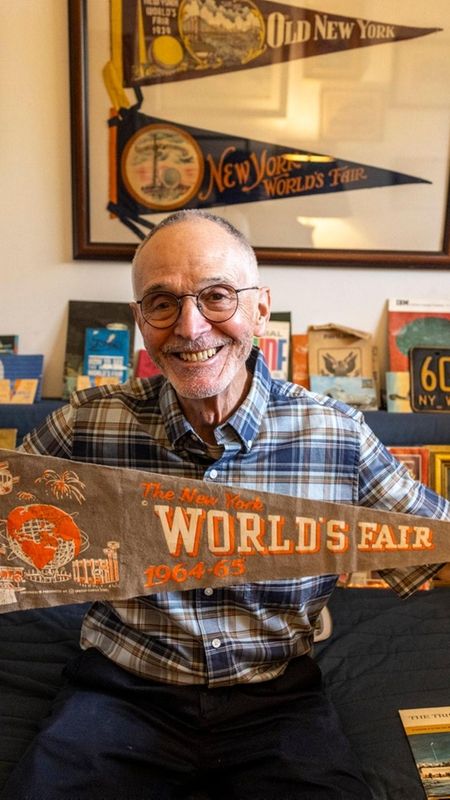

Retired police officer Pat Mazza Jr. shows off his collection from the 1964 Worlds Fair at his Massapequa home on May 2. Credit: Newsday/J. Conrad Williams Jr.

PROJECTED DEMAND

Phil Weiss, who has auctioned off many World’s Fair collections over the decades, sees the demand for 1964 collectibles falling as the years pass.

“You don’t have a lot of people who remember those fairs,” says the owner of Weiss Auctions in Lynbrook.

Pat Mazza Jr. has a collection of items from the 1964 World's Fair at his Massapequa home. Credit: J. Conrad Williams Jr.

Mazza hopes to sell the Philippines Pavilion’s leftover stock that he bought for a few hundred dollars from a friend whose parents ran the pavilion. He has embroidered cloth purses in their plastic wrap, dozens of World’s Fair purses and several gold necklace medallions.

But he’ll never part with his file of Dinoland photos and ephemera, which belonged to the exhibit sponsor, the Sinclair Oil company, whose logo is a dinosaur.

Not only is it the rarest item in his collection — he paid $175 for it 25 years ago but values it closer to $1,200 now — Dinoland is part of his childhood, when his father was still alive. Life then was about toys and cartoons for him.

“It was a time in life for me with no responsibilities,” Mazza says. “What I wouldn’t do to go back to the ’64-'65 World’s Fair.”