This is a modal window.

Horses are dying at Belmont Park at rates greater than the national average.

The iconic venue has 65 barns and houses about 2,000 horses.

It’s home to the Belmont Stakes, the third and most difficult leg of the Triple Crown.

The race attracts 50,000 fans each year.

But even on the park’s most exciting day last year …

… tragedy struck as 4-year-old Excursionniste went down during the final race.

He was one of

horses who died at Belmont Park in the past five years.

Racehorses at Belmont Park are dying at higher rates

Excursionniste sprinted out of the gate in the final race on Belmont Stakes day a year ago. He led the field of a dozen at the first turn and was second at the half-mile mark.

As the sun set over the racetrack in Elmont, Excursionniste never crossed the finish line. When the 4-year-old dark bay thoroughbred approached the final straightaway, he suffered a catastrophic injury to his left front leg. State records detail a shattered sesamoid bone and ruptured cartilage and ligaments.

Racetrack veterinarians euthanized the horse on the track. A makeshift wall was pulled in to prevent those who remained from the nearly 50,000 there for one of racing’s biggest days from witnessing a horse’s death.

Many other horses have met a similar fate at Belmont. Excursionniste was one of 221 that died from racing or training injuries or other medical conditions in five years, state records show.

A yearlong Newsday investigation into horse deaths at Belmont involving the review of death certificates, necropsies, state investigative documents and more than a dozen interviews found that thoroughbreds have died at higher rates there than at other racetracks despite state and racing officials’ multipronged efforts for more than a decade to reduce racing deaths.

Horses died from injuries while racing at Belmont last year at a greater rate than the national average for the third straight year, according to The Jockey Club, a horse racing advocacy group based in New York City. The track’s racing fatality rate has risen in seven of the last eight years, a Newsday analysis of state records shows. Meanwhile, more than twice as many horses died from injuries sustained during training than racing at Belmont, and an average of 15 horses die each year from non-racing injuries, illnesses or medical conditions, state records show.

State and national racing officials say the deaths at Belmont are no worse than elsewhere because the uptick represents a small percentage of the horses that race. They say the deaths should be presented against the many thousands of horses that run and train annually. Belmont has 2,200 stables, among the most of any racetrack nationwide, they noted.

“It’s a rare event,” said Dr. Scott Palmer, who as the state Gaming Commission’s equine medical director is responsible for the safety of racehorses. “Now, it's a horrific event … But, it's a rare event.”

Many outside the industry say the deaths are still too frequent.

“If it is so rare, why do we hear about it all the time?” said equine veterinarian Dr. Kraig Kulikowski, of upstate Ballston Spa. “It's not rare enough.”

This is a modal window.

Thoroughbred horse racing, a multibillion-dollar industry, has experienced deaths at high-profile moments. In 2023, horses died at each of the Triple Crown racetracks hours removed from the nationally televised races that serve as a celebration for the sport’s rich history.

Those deaths, along with clusters of fatalities at Kentucky’s Churchill Downs and Saratoga, reignited existential questions about the humanity of horse racing.

Horse racing has temporarily stopped at Belmont for two years as construction is underway on $555 million in improvements. The New York Racing Association is funding $100 million in new racetrack surfaces, including a synthetic track studies have shown reduces horse fatalities by half.

“NYRA is constructing a new Belmont Park that will set the gold standard for equine health and safety,” NYRA spokesman Pat McKenna said. Saturday's Belmont Stakes was moved to Saratoga.

Amid construction, about 2,000 horses remain stabled at the Elmont facility and continue to train on Belmont’s training track. They are shipped back and forth to Aqueduct for races. Aqueduct, located west of Kennedy Airport in Queens, will permanently close when the new Belmont reopens.

But horse deaths continue. This year, 14 horses have died at Belmont — eight from injuries sustained during training and six from non-racing injuries such as illnesses or medical conditions, records show. The horses ranged in age from 2 to 9.

Workout at sunrise in Belmont Park in Elmont on June 28, 2021. Credit: Newsday/J. Conrad Williams Jr.

Palmer said he spends his days as the state's equine medical director looking for ways to make racing safer for the horses to preserve a sport that he said has “a broad base of appeal.”

“Any sport that has fatalities has a problem, absolutely,” Palmer said. “Because there are fatalities, it’s our responsibility as the steward of the horse to minimize the risk for that.”

Death records reveal injuries

Newsday reviewed more than a thousand pages of medical records and state investigative documents about the horses that died at Belmont between 2020 and 2023. The records were obtained through Freedom of Information Law requests to the state Gaming Commission, which regulates horse racing.

For a horse, a leg fracture can be catastrophic.

Excursionniste's owner, Little Blue Bird Stables, posted on Facebook about the horse's death at Belmont Park on June 10, 2023. Credit: Little Blue Bird Stables

Bone breaks and ligament tears need time and rest to heal, a luxury that 1,100-pound horses don’t have because they stand on all four legs all the time, including when they are sleeping.

In the case of Excursionniste, the horse that died on Belmont Stakes day last year, his trainer, Mark Hennig, told the state Gaming Commission that the horse had been in “excellent” physical condition before the race at Belmont. But state records show the horse had health issues.

In a questionnaire provided to state investigators following Excursionniste’s death, Hennig said X-rays on the horse’s other front leg “had no significant findings.” He provided no reason why a veterinarian wanted a closer look at that leg’s fetlock, or ankle, which equine experts say is the joint that most commonly leads to a horse’s death on the track.

The horse received an injection of an anti-inflammatory drug and joint fluid replacement eight months before the Belmont race, Hennig wrote. He added that the horse received a different anti-inflammatory drug 72 hours before the race and additional joint medications 48 hours prior.

Hennig and the horse’s owner, Little Blue Bird Stables LLC, of Austin, Texas, did not return messages seeking comment.

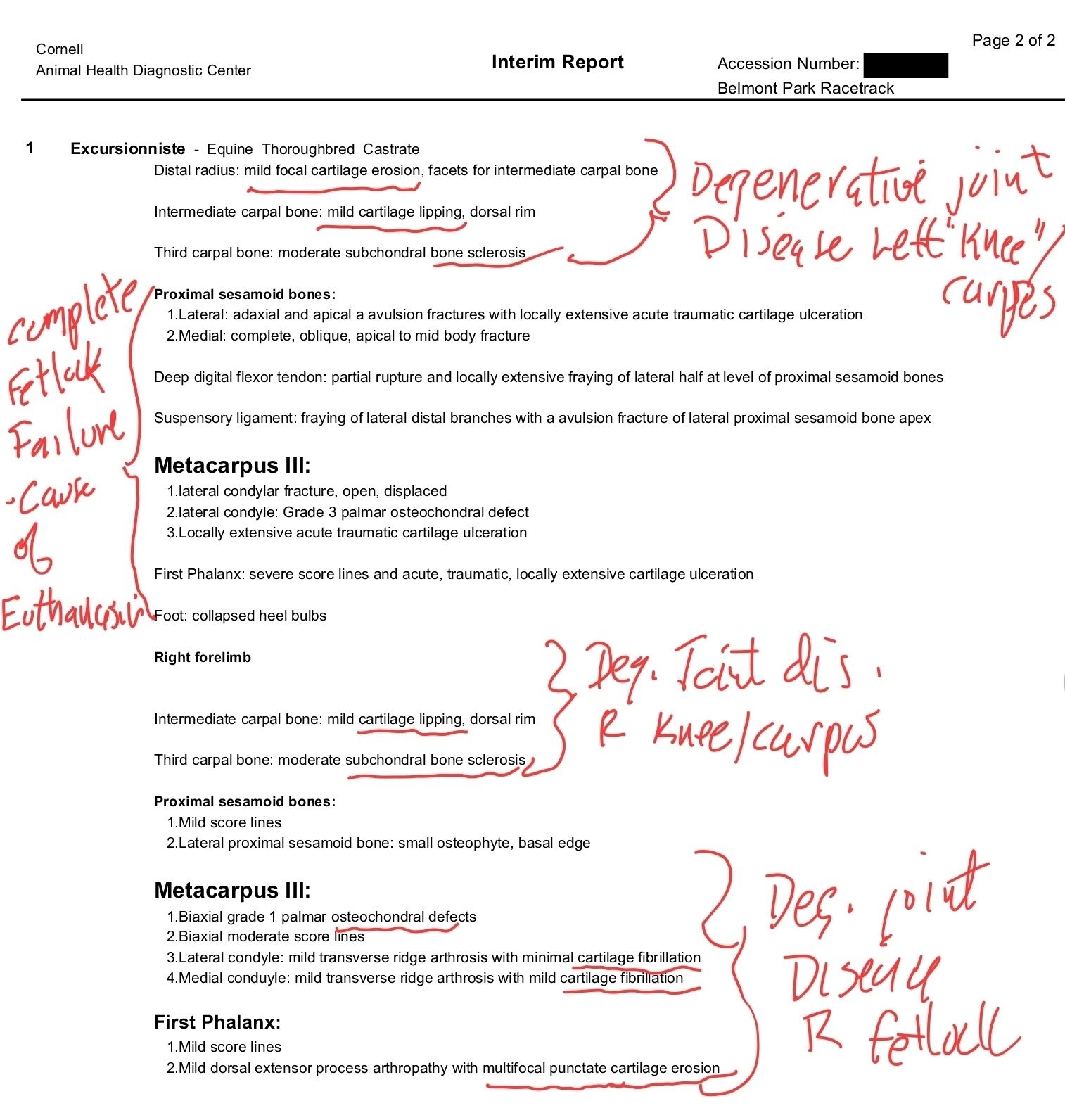

Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine examined the horse after it was euthanized and produced a two-page necropsy report detailing degrees of disease found in the horse’s body.

Kulikowski, the equine veterinarian, reviewed the report for Newsday. He said the pathologists found varying degrees of degenerative joint disease in every joint it examined — especially abnormal for a 4-year-old horse.

“If it didn’t die from this fetlock failure, it was going to spend the next 24 years dealing with all this other degenerative joint disease, all this other pain and suffering,” Kulikowski said. “And, I think to me, that’s really the understated problem.”

The necropsy of Excursionniste showed degenerative joint disease in every joint that was examined, equine veterinarian Kraig Kulikowski said.

See full reportPalmer, the state's equine medical director, said identifying pre-existing injuries in horses is a challenge. Trainers, he said, long have been fearful of reporting injuries “because they are afraid that I will take the horse away from their income stream, and I get that, OK.”

Palmer hopes advancements in wearable artificial intelligence units that indicate changes in a horse’s gait and speed will help provide objective data to indicate when a horse is ailing.

Asked about the findings of degenerative joint disease in necropsies, he said, “Am I surprised that there's arthritis in athletes that are competing at high speeds for long periods of time? No, I'm not. That’s to be expected.”

In a 17-race career beginning in 2021, Excursionniste placed in the top three seven times: one win, two seconds and four third-place finishes. He earned $139,470, an average of $8,204 per start, according to Equibase, the industry’s record keeper.

Excursionniste completed seven timed workouts in 2023, all at Belmont, the last taking place on May 2. He raced for the first time that year on May 14, also at Belmont, and finished fourth. He did not complete another timed training run before his fatal race at Belmont on June 10.

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, an outspoken critic of horse racing, asked the state Gaming Commission to investigate Excursionniste’s owner and trainer following his death. PETA cited emails it said it obtained from a whistleblower that say Hennig sidelined Excursionniste from training before his fatal race because of an injured right ankle.

The state Gaming Commission’s “review of the facts and circumstances … found no evidence” that Excursionniste and another horse trained by Hennig that died at Belmont the next day were unfit to race, spokesman Lee Park said this week.

PETA said it received the same message on Tuesday, nearly a year after it asked for an investigation. “The usual response,” said Kathy Guillermo, PETA senior vice president. “Two dead horses who were injured or sore not long before the races in which they died, but it’s all good.”

Belmont's numbers rising

A screen is put up as Helwan, which ran in the fourth race before the Belmont Stakes, was put down at Belmont Park on June 6, 2015. Photo by John Roca. Credit: John Roca

New York has been working on reducing horse deaths since then-Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo convened a task force in 2012 following 21 fatalities at Aqueduct in four months.

The task force, chaired by Palmer, produced a 209-page report with a series of recommendations. They included mandating necropsies after all racehorse deaths to identify causes and preexisting conditions; employing staff to investigate each death by interviewing trainers, jockeys and veterinarians; adopting rules to strengthen drug testing, and improving the consistency of the track surfaces.

The report also recommended hiring an equine medical director. The state Gaming Commission hired Palmer in 2014 as the equine medical director. He earned $273,737 in 2022, state records show.

Not all recommendations stuck. Palmer initially wanted a mortality review board to discuss each fatality with the horse’s trainer following an investigation. He said it was too difficult to schedule.

Still, the task force claimed success when horse deaths from racing dropped in half almost immediately across the state.

Belmont’s racing death rate dropped even further, to 0.8 horse deaths per every 1,000 horses that started a race in 2013, down from 2.2 in 2012, according to a Newsday analysis of state records.

But Belmont's death rate has risen in recent years, from a low of 0.7 in 2015 to 2.1 last year.

Although Palmer celebrated the initial decline in deaths, he said in an interview in April that it's not appropriate to reach any conclusions about the subsequent rise in the racing fatality rate at Belmont. There are too many variables out of their control that lead to deaths, he said.

“We’re seeing a little bit of a rise — it’s never flat, it goes up, it goes down, it goes up, it goes down — and it does that because of variability in the data,” Palmer said. “Again, it’s rare events, so if you have one fatality difference in a year out of 1,000 starts, that will bump you up.”

Belmont under construction

Construction at Belmont Park on May 17, 2024. Credit: Newsday/J. Conrad Williams Jr.

New York state officials, meanwhile, are betting on horse racing as part of “a world-class sports and entertainment destination” at the state-owned 400-plus-acre Belmont property that already houses the Islanders’ 3-year-old 17,255-seat arena.

The upgrades also include a synthetic track designed to cut horse fatalities, a new infield accessible to fans, tunnels and overall layout. A $455 million state loan is financing a new 7,500-seat grandstand with modern dining and suites. State legislators approved the loan as part of the 2024 state budget.

NYRA officials say the modernized Belmont track surface and drainage system will improve horse safety.

NYRA is replacing Belmont’s nearly 60-year-old clay track with a limestone base topped with a clay pad that they say “responds exceedingly well to extreme rainfall” and “offers a more forgiving surface.” NYRA said it installed the same surface at the Saratoga training track and noted how it led to a reduction in catastrophic injuries.

The new Belmont facility, set to open in 2026, will lead to $155 million in annual economic output and $10 million in new tax revenue, Gov. Kathy Hochul said. The renovation will “provide an enhanced experience for customers attending the iconic Belmont Stakes for generations to come,” she said.

Animal welfare activists opposed the state loan and filed a lawsuit alleging the loan was unconstitutional because public money was used to benefit a private corporation. State Supreme Court Justice Peter Lynch of Albany County dismissed the lawsuit; the activists – Jannette Patterson of Manhattan and John Di Leonardo of Moriches – are appealing.

New York needs to let this cruel industry either stand on its own or die.

“New York needs to let this cruel industry either stand on its own or die, like the more than 30 horses who were killed at Belmont just last year alone,” said Di Leonardo, executive director of Humane Long Island, an animal advocacy organization.

Gambling fuels people’s interest. In May, bettors wagered more than $320 million on the Kentucky Derby's daylong race program, which the racetrack said was a record. NBC announced 16.7 million viewers tuned in, the most since 1989.

A surprising find

Dr. Scott Palmer, equine medical director for the New York State Gaming Commission, at Aqueduct Racetrack in Queens. Palmer is responsible for equine health and safety at New York racetracks. Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

When the issue turns to animal welfare groups and activists referring to New York racetracks as killing grounds, Palmer’s face turns red, his voice reaches a lower pitch and the pace of his storytelling slows.

Palmer’s life work has been caring for horses, having graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine in 1976. He worked as a staff clinician at the New Jersey Equine Clinic and became the hospital’s director in 1997. He also teaches at Cornell and has published dozens of peer-reviewed research papers about horse pathology.

Interested in disproving horse racing’s critics, Palmer searched national statistics on horse mortality, not just at racetracks. What he found surprised him, he said.

Horses die no more often at racetracks than anywhere else in the country, Palmer said. He announced his findings in a speech before state Gaming Commission members in October, two months after 14 horses died during Saratoga’s summer meet, leading to an investigation by the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority. Congress created HISA in 2020 to regulate the industry.

He said the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Animal Health Monitoring System surveys private farm owners across the country about how many horses, mules and donkeys are on their grounds and how many died in the past year.

The most recent survey, from 2015, listed a fatality rate of 1.4%, which is similar to the rate at New York’s racetracks, he said.

“These statistics indicate that horses that race in New York are as safe if not more so than those that live on farms in non-racing capacities,” he told the Gaming Commission.

In an interview with Newsday in April, Palmer added: “There are people who would make you believe that the racetrack is a killing ground. And I object to that.”

Dr. Kraig Kulikowski, equine veterinarian at his stables in Balston Spa, New York. Kulikowski spoke out in 2019 against horseracing, citing horse deaths and lifelong injuries. Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

Kulikowski, the Ballston Spa equine veterinarian, said Palmer’s statistical comparison is “very misleading.” That's because Palmer compares the death rate of racehorses most commonly between the ages of 2 and 8 with horses of all ages. Horses can live more than 30 years, Kulikowski said.

"Those horses are dying from basically natural causes. And somehow that's the same as running until their limb snaps off?" Kulikowski said. That's "just so disingenuous."

He added, “It’s the same junk science that the thoroughbred industry typically uses to try to make their point.”

When Kulikowski’s comments were sent by email to Palmer, a spokesman for the state Gaming Commission wrote: “Dr. Palmer acknowledged that the causes of death were different and the age distribution is also different, but it does not change the fact that the comparison is of an overall average mortality rate for both groups. That means all deaths — no matter the cause, no matter the age.”

National oversight of sport

Tapit Shoes works out during Belmont Stakes week in Elmont on June 7, 2023. Credit: Newsday/J. Conrad Williams Jr.

HISA, the agency created by Congress under the Federal Trade Commission, is responsible for regulating horse racing nationwide, particularly focused on horse safety. The agency began enforcing a nationwide standardized anti-doping program last year, just before the Belmont Stakes.

The program came after an FBI investigation into racehorse doping that led to federal criminal charges against 27 people, including trainers Jorge Navarro and Jason Servis. Both pleaded guilty to roles in their horses using either unapproved or misbranded drugs. Navarro was ordered to pay $26.9 million in restitution and is serving a 5-year sentence; Servis is serving a 4-year sentence.

When the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York announced the indictments in March 2020, Palmer said people told him, “Oh my God, what a horrible thing.” Palmer said he quickly corrected them. “I said, ‘This is the greatest thing. Finally we're going to be able to really make some headway here.’ ”

Palmer hopes the deterrence of the FBI’s involvement combined with HISA’s drug testing program helps horse racing tackle a doping issue, the depths of which may not be fully understood yet.

HISA chief executive Lisa Lazarus, a longtime sports attorney who spent nine years working for the National Football League, cited horse racing's place as one of America’s oldest sports as a primary reason why the sport remains an important part of American culture.

Asked if the sport has a problem with horse deaths, Lazarus said, “It’s completely unacceptable for horses to get injured or die in the racetrack. I also know that horse racing has never been safer than it is today. And that it’s going to keep getting safer.”

HISA says it strives to improve horse racing’s transparency and accountability, two issues that have dogged the sport. In April, HISA released its first fatality report, reporting that 1.23 horses died in 2023 for every 1,000 horses that started a race at HISA-regulated tracks.

Belmont’s racing death rate in 2023 was 2.12 per 1,000 race-starts, up from 1.94 in 2022, according to The Jockey Club, the horse racing advocacy group.

Critics say the metric HISA used to count racehorse deaths is flawed because it includes only horses that died from racing within 72 hours of a race, while not taking into account horses that die from training or other medical reasons.

HISA spokeswoman Mandy Minger said the organization followed the same fatality reporting measures by The Jockey Club for its first report only “so that the industry could compare fatality numbers under HISA to previous years.”

She said HISA “did not have the sufficient mechanisms in place to reliably count training fatalities” at the start of 2023. That’s been fixed, she said, and those deaths will be reported in next year’s report.

The Jockey Club has published racing-death counts by track since 2009. It has not published training deaths because the information it receives voluntarily from racetracks nationwide “is often incomplete,” spokeswoman Shannon Luce said.

HISA also commissioned investigations into the cluster of deaths at Churchill Downs and Saratoga, and posted reports on its website that were long on words and short on answers. The investigations concluded no one reason existed for the deaths.

Instead, they cited a confluence of explanations, such as track surface, heavy rain and pre-existing injuries.

“When you talk about a horse getting injured and we say it's multifactorial, it’s not a copout,” Lazarus said. “It’s just that’s an honest explanation: There’s more than one factor. It’s not that we don’t know why; there's seven or eight reasons that maybe contributed.”

Among the reasons HISA cites: a horse’s pre-existing injuries, turf conditions after heavy rainfalls and the difficulty in surgically repairing a horse’s leg.

Gut punch to 'whole community'

Dr. Sarah Hinchliffe, the director of Veterinary Department of the New York Racing Association, says it's very difficult dealing with a fatal injury to any of the horses. Credit: Newsday

NYRA regulatory veterinarian Dr. Sarah Hinchliffe often is the last person to see a horse before it dies on a New York racetrack, including Belmont.

She examines horses on the morning of races to clear them to run, then views them one last time before they enter the starting gate. She has the authority to scratch a horse from racing against the will of the trainer.

Most trainers are agreeable when Hinchliffe scratches a horse hours before a scheduled race, but it’s a tougher decision for a once-in-a-lifetime race like the Belmont Stakes, she said.

When a horse breaks down on the track, she races to the scene. In an interview at Belmont in May, tears trickled down her face as she answered a question about being on the track to euthanize Excursionniste at the Belmont Stakes last year.

“It is incredibly difficult for us,” Hinchliffe said. “It's not that we don't care. It's not that. I mean, we put aside feelings when we're out there because we have to do what’s best for the horse. But it takes a toll on us mentally as well.”

“When you see a horse go down, that's a gut punch to our whole community,” said Joe Appelbaum, of Manhattan, a longtime owner and breeder.

Added Glen Kozak, NYRA’s executive vice president in charge of the track maintenance: “If it doesn't impact you and bother you, you shouldn’t be doing this.”

It’s tough to convince people of that, trainers said, because of how they financially benefit from a horse’s success.

“Every time we run a horse, I say a prayer,” said trainer Jena Antonucci, whose horse Arcangelo won the Belmont Stakes last year, making her the first female trainer to win in the race’s 155 years. “Every time."

Unenviable position

Palmer, the state’s equine medical director, often faces criticism from both animal rights activists and horse racing trainers.

“I am a scientist, and I am a voice of calm in a world of drama and contention,” Palmer said. “A world of drama for sure, that’s horse racing.”

To Kulikowski, Palmer protects the horse racing industry.

To Palmer, some trainers view regulations, drug testing, and perhaps even his presence, as a risk to their primary business interest: preparing a racehorse to be at its optimal state on race day.

Palmer said he is trying to change a culture. For example, he said when he started, whenever a horse died, the trainer almost always blamed it on “a bad step.”

There is no such thing as a bad step.

“There is no such thing as a bad step,” he said. “You know, that doesn’t make any sense.”

Kulikowski agrees.

“It’s very much an oversimplification of the problems that they’re having, and they want to make it seem like this is a one-off thing and it's not going to happen again,” he said.

In a decade on the job, Palmer said he believes he has changed people’s thinking about horse racing deaths, citing questions trainers are asked following each fatality.

The 20-question document asks about past injuries, illnesses, medications, even the trainer’s impression of the track surface that day. Palmer said he reviews the answers and looks for trends.

There’s also a line that asks, “What do you think caused this injury? Any special circumstances?”

Hennig, the trainer for Excursionniste, the horse that died on Belmont Stakes day last year, answered with three words.

“Very unfortunate step.”

With Anastasia Valeeva

Reporter: Jim Baumbach

Additional reporting: Anastasia Valeeva

Editors: Keith Herbert, Rochell Bishop Sleets, Don Hudson

Photo editor: John Keating

Video editor: Jeffrey Basinger

Videographers and photographers: Thomas A. Ferrara, Steve Pfost, James Escher, J. Conrad Williams Jr., John Roca, Jeffrey Basinger, Howard Schnapp

Video producers: Jim Baumbach, Robert Cassidy and John Keating

Multimedia Journalist: Jamie Stuart

Digital design: James Stewart, Jen Brown, Mark Levitas

Digital development: TC McCarthy

Project manager: Tara Conry

Assistant project manager: Nicholas Klopsis

Copy editing: Estelle Lander

Additional research: Caroline Curtin, Laura Mann

Social media: Priscilla Korb

Quality Assurance: Sumeet Kaur

Print design: Jessica Asbury

This is a modal window.

LI quality of life poll ... LI Volunteers: Stony Brook Hospital ... Get the latest news and more great videos at NewsdayTV

This is a modal window.

LI quality of life poll ... LI Volunteers: Stony Brook Hospital ... Get the latest news and more great videos at NewsdayTV

Most Popular