Suffolk County’s cybersecurity chief suspected that county employees were bitcoin mining in 2017 — nearly four years before authorities uncovered an illegal mining operation that officials say helped open up the county’s computer network to a devastating ransomware attack, according to an employee’s sworn statement filed in the court case.

Other county employees discussed seeing bitcoin mining devices in the county data center in the county clerk’s office, and a county systems analyst took photos of 10 bitcoin mining devices he saw in the data center and showed them to his boss, recently released court records show.

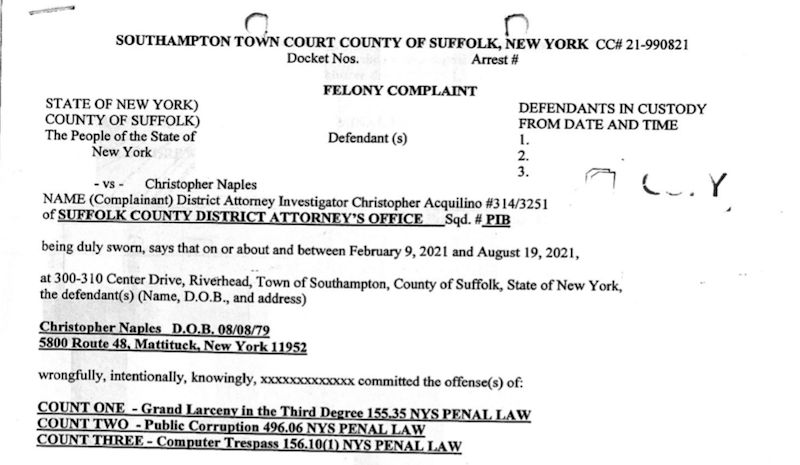

But it wasn’t until July 2021 that a county official notified the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office, which immediately opened an investigation. That resulted in the Sept. 8, 2021, arrest of Christopher Naples, 43, assistant manager of information technology in the clerk’s office, for allegedly running the illegal operation.

The district attorney's investigation relied on computer-savvy detectives and old-school police work, including hidden-camera surveillance.

WHAT TO KNOW

- Cybersecurity experts said that the bitcoin mining might have contributed to a ransomware attack in Suffolk County.

- Investigators found 46 bitcoin miners.

- Bitcoin is a form of cryptocurrency.

Naples, who admitted to detectives that he installed the bitcoin mining devices to make money, was charged with grand larceny in the third degree, public corruption and computer trespass.

A forensic auditor calculated that Naples stole at least $6,477 in electricity from Suffolk County to run the bitcoin mining equipment, court records show.

Launched in 2009, bitcoin doesn't exist as physical bills or coins, but as blocks of data that feature a digital signature each time they are moved from one owner to another. Its value has varied significantly in the last few years. Bitcoin mining involves running complex calculations to encrypt blocks of data.

Naples, of Mattituck, has been suspended with pay. He earned $149,721 last year, according to payroll records. He has not responded to interview requests. His attorney, William Keahon, said he expected the case to be resolved soon. Naples has another court date in May.

The court records show for the first time that county IT professionals working in County Executive Steve Bellone's administration were aware of the illegal bitcoin mining. The Suffolk clerk is an independently elected office, but its data center is under the purview of the county's Department of Information Technology.

The question for management, said John Bandler, who teaches cybersecurity at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan, is, “How did it allow this to happen essentially in the open and for so long?”

Suffolk officials, including Chief Deputy County Executive Lisa Black and IT Commissioner Scott Mastellon, did not respond to numerous requests for interviews. Deputy County Executive Vanessa Baird-Streeter said: "We will not comment on a pending criminal matter being prosecuted by the district attorney's office."

Cybersecurity experts interviewed by Newsday said the bitcoin mining might have contributed to opening up the county’s system to the ransomware attack. Bellone last year released a report on the cyberattack that found it started in the county clerk's office as early December 2021; took advantage of a common security flaw in computer systems; and spread throughout the computer network, halting the county's websites and servers. In the months after Naples' arrest, the county clerk's office sought a security upgrade, but a steering committee — chaired by the county IT commissioner — rebuffed it, according to emails obtained by Newsday.

"The issue is that there are so many other attacks on municipalities around the country that are going through this. So, are they related? Possibly. Probably. Certainly, I think there’s a huge chance it was,” said Michael Nizich, director of the Entrepreneurship and Technology and Innovation Center at New York Institute of Technology.

Will Cong, Cornell University Rudd Family professor of management, said the bitcoin mining may have indirectly increased the county’s exposure to a ransomware attack, just as browsing certain websites does.

Attorney William Keahon is representing Christopher Naples, the Suffolk County employee who allegedly ran an illegal bitcoin mining operation. Credit: James Carbone

Bellone suggested in a December news conference that Naples, “the architect of the clerk’s IT environment,” for years delayed a key security upgrade that could have blocked the ransomware attack because he didn’t want outsiders discovering his illegal mining operation.

Keahon disputed that.

“He’ll do everything he can to shift the blame,” he said of Bellone.

In response to Keahon, Baird-Streeter, the deputy county executive, said: "No official forensic examination has been released nor has the Legislature conducted their review, obviously."

The full court file lays out the suspicions of county IT employees and their unease with the unusual devices they saw not just in the data center but around Naples’ desk. The file also paints a picture of an increasingly brazen Naples, who kept bringing in more bitcoin mining devices, even after a subordinate asked about them. There were so many devices — 46 in all — that they raised the temperature in the data center by 20 degrees and set off alarms.

Nonetheless, the court file shows, IT employees were reluctant to remove them, despite the damage the high heat could do to other equipment, or even to confront Naples.

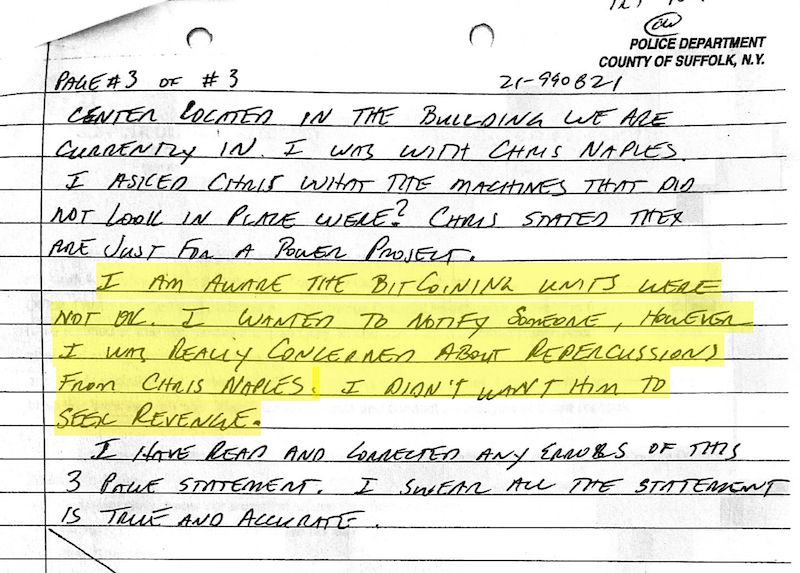

One systems analyst, Christopher Rizopoulos, who worked for Naples, told detectives in a statement: “I am aware the bitcoining units were not OK. I wanted to notify someone. However, I was really concerned about repercussions from Chris Naples. I didn’t want him to seek revenge.”

Naples started working at the clerk’s office in 2000 at the age of 21 under then-Clerk Ed Romaine, who is now the Brookhaven' Town supervisor. Naples’ father, builder Jim Naples Sr., has contributed money to Romaine's political campaigns, giving at least $7,650, state records show.

Jim Naples Sr. also contributed at least $2,300 to Judy Pascale, who followed Romaine as clerk.

Rizopoulos also told detectives that in 2017, Brian Bartholomew, the county’s information security coordinator, said, “These guys are bitmining.”

The Suffolk County Clerk's office, where employees reported seeing bitcoin mining devices. Credit: Chris Ware

Bartholomew’s attorney, Ray Doyle, declined to comment. Rizopoulos did not respond to requests for an interview.

Another systems analyst, Matthew Ballantine, became alarmed when he noticed the excessive heat in the data center.

“I know that heat is not good for the equipment, so I looked for the source of the heat,” he said in a statement to investigators. “That’s what caused me to find several devices that appeared to be hidden inside the server racks.”

At first, Ballantine wasn’t sure what they were and thought there might be a legitimate reason for them. Later in the day, he realized that they might be bitcoin miners. But because he wasn’t authorized to remove the equipment, he instead told Vincent Cordiale, assistant manager of IT operations. Ballantine offered to photograph the equipment the next time he was in the data center. He took the photos of 10 bitcoin miners on Feb. 9, 2021, and showed them to Cordiale.

Ballantine and Cordiale did not respond to requests for interviews.

Around July 16, 2021, Ballantine returned to the data center with several other systems analysts to work on some network problems. One analyst, Anthony Oliveto, noticed the excessive heat. Ballantine pointed out the devices and saw additional ones sitting atop server racks, according to his statement.

“None of us had any more conversations about the equipment, but I believe everyone had an understanding that they were miners that probably did not belong in the data center,” Ballantine said in his statement.

An IT employee who is not named in court records told his superiors, who notified the Suffolk district attorney, according to a statement by district attorney investigator Christopher Acquilino, who led the investigation.

What followed was an investigation marked both by technical complexity and cloak-and-dagger technique, such as entering the building in the middle of the night to install covert video equipment.

On July 29, 2021, special investigator John Primiano and systems analyst Mark Enoch visited the data center after employees left, about 6:45 p.m. They immediately noticed the high heat — it was 89 degrees — and saw an LCD display flashing a red warning light as a high-temperature alarm, despite several large fans in the room. The ideal temperature is just under 70 degrees.

Several branch circuits were nearing overload, as the miners were connected to county power strips. They also noticed that someone had put duct tape over the miners’ identification labels, according to Primiano’s statement.

They counted 21 bitcoin miners.

About five hours later at 12:15 a.m., investigators installed a video camera system in the public corridor next to the data center, according to Primiano’s statement. They finished by 2 a.m. and left the building.

Their nighttime work paid off. They saw Naples installing one of the devices in the data center, according to Acquilino’s statement.

District attorney investigators executed a search warrant on Aug. 19, 2021. This time, they found 46 machines.

“SCDAO investigators found devices in server racks, on top of server racks, on Naples’ desk, under removable floorboards in the data center and in an unused electrical wall panel,” according to Acquilino’s statement.

Equipment used in the illegal bitcoin mining operation that Suffolk authorities displayed in 2021. Credit: John Roca

Naples showed up at 11:30 a.m. District attorney investigators searched the data center and Naples agreed to answer questions, according to Primiano’s statement. Naples acknowledged that he installed the miners to earn money and “indicated that he bought the servers from eBay and 'they were six for $90.' "

Two hours after investigators removed the machines, the temperature in the data center dropped 20 degrees.

Just how much Naples earned in cryptocurrency is not revealed in the court file. But at the time he was mining, a single bitcoin was worth $30,000 to $40,000, Cong said.

A bitcoin is now worth about $28,000.

Bitcoin is a form of cryptocurrency. It is based on what is known as the blockchain, which is a series of data points linked together. The blockchain serves as a public ledger that anyone can see. Each block in the chain is encrypted through a highly complex and secure algorithm. Because no one has been able to break the code, it is extremely valuable, Nizich said.

Adding a block to the chain requires that somebody make sure that the encryption was done right. That’s called “proof of work,” which is the same as bitcoin mining. That’s done through a complex mathematical process. When someone successfully completes a proof of work, the reward is a bitcoin. Because people all over the world are trying to solve the same mathematical problems, there’s intense competition, Nizich said.

“So you have to have a really good algorithm and a really powerful device — not just a single computer or PC — you have to have a very special device, using what is called an ASIC processor, or you have to have some sort of distributing process level. It wouldn’t be something you’d have usually in your home office,” he said.

Naples’ operation was “extremely sophisticated,” he said.

Because these devices use enormous amounts of energy, it’s not practical to do it at home. A single device uses the same amount it takes to run a house for 24 hours in just 45 minutes, Nizich said.

A conservative estimate of the cost of the electricity used by Naples' machines was $6,477 from Feb. 10, 2021, though Aug. 10, 2021, according to the court file.

The machines also used so much county bandwidth that employees working on the weekend couldn’t access the internet, Bellone said in December.

HOW BITCOIN WORKS

Bitcoin, the most widely recognized form of cryptocurrency, is based on what is known as a blockchain, a shared database that serves as a public ledger for cryptocurrency. Each block in the chain is encrypted through a highly complex algorithm. That encryption makes the block immutable and valuable.

Adding a block to the chain requires that somebody — a bitcoin miner — makes sure that the encryption was done correctly. That “proof of work” is the essence of bitcoin mining, done through complex computational mathematics that is costly in electricity and computing power. When someone successfully completes a proof of work, the reward is a bitcoin. Because people all over the world are trying to solve the same mathematical problems, there’s intense competition.

Gaetz withdraws as Trump's AG pick ... Sands Meadowbrook proposal ... Bethpage FCU changes name ... Cost of Bethpage cleanup