Long Island public school districts persuaded more than 100 tenured educators accused of misconduct — including sexual and physical — in the past decade to resign by continuing to pay their salaries and concealing the reasons for their exits, a Newsday investigation found.

School districts withheld their names from the public and approved "confidential" settlements that provided limited or no details. Two deals bolstered pension benefits by keeping the teachers on the payroll for years while banning them from contacting students and barring them from school grounds.

Besides compelling 103 educators to resign, school districts also negotiated lesser penalties, such as unpaid suspensions, paid leaves, counseling, fines and reprimands with another 114 who faced misconduct allegations.

In a first-ever investigation into teacher discipline on Long Island, Newsday spent more than three years reviewing more than 5,000 pages of school and state disciplinary records spanning more than a decade, all obtained through hundreds of Freedom of Information Law requests.

Newsday found school districts:

- Shielded most details about alleged teacher wrongdoing. Districts provided Newsday detailed records only in a few dozen cases, in which a state-appointed hearing officer decided the discipline.

- Omitted the alleged misconduct from agreements that led to the educator’s departure. Once the district secures a teacher’s resignation, experts said school officials lose motivation to detail what behavior compelled them to seek discipline.

- Paid teachers to leave. The payouts represented salary teachers would have received while awaiting a state disciplinary hearing, on top of contractually obligated payments for unused sick and personal time.

Teacher discipline has been at the forefront on Long Island since an hourslong Babylon Board of Education meeting in November 2021, when former students accused a dozen teachers of sexual misconduct and blamed the school district for mishandling the allegations. The state attorney general launched an investigation that is ongoing.

Babylon in January filed state disciplinary charges against two teachers who had been on paid leave since that meeting, formally beginning the state-mandated process to potentially terminate a tenured educator. Babylon declined to identify the teachers.

They are protecting the teacher more than they are protecting the student.

— Darcy Bennet, Babylon alumna

Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

“They’re protecting the teacher more than they are protecting the student,” said Darcy Bennet, referring to Long Island schools' use of the teacher discipline system. Bennet, 32, a Babylon Junior-Senior High School alumna, recently learned of confidential agreements involving a teacher she said she reported for trying to kiss her when she was a ninth-grader.

Long Island districts insist they discipline teachers appropriately. They said they prefer negotiating a teacher’s resignation instead of taking the case to a state-appointed hearing officer because it's quicker and saves taxpayers money.

“People may not believe it, but this whole process is taken very seriously — by superintendents, by boards, by principals,” said attorney John Gross, of Hauppauge-based Ingerman Smith, which represents 43 Long Island districts. “It’s not done lightly.”

When a school district seeks to discipline a tenured educator, state law calls for districts to file charges with the state Education Department to seek penalties ranging from fines and reprimands to suspensions and termination determined by an impartial hearing officer.

The Brentwood district reached a settlement in November in which longtime high school biology teacher Christopher Amato resigned, compelling the district to abandon its case to terminate him. No reason is given in the paperwork for his departure.

Amato's resignation came after a former student alleged he inappropriately touched her in his classroom a decade ago. The ex-student said she worked with the school district's lawyers on their case seeking his termination. Amato's attorney called the allegations "a complete fabrication."

"Your ultimate goal is obviously to remove the teacher from ever being in front of kids, which we did," Brentwood Superintendent Richard Loeschner said.

Editor's note

In a first-of-its kind investigation on Long Island, Newsday has uncovered details about how public school districts and the state of New York impose discipline upon educators. Newsday found that Island districts persuaded at least 103 tenured educators accused of misconduct in the past decade to resign by continuing to pay their salaries for months and concealing the reasons for their exit. Using confidential agreements, districts withheld the names of the educators from the public and approved the settlements while providing limited or few details about what sparked the resignations.

Reporters Jim Baumbach and Joie Tyrrell have been investigating teacher discipline since 2018. They found records detailing teacher misconduct ranging from physical contact with students to theft of money to sexual harassment to showing inappropriate material to students in class.

Teacher discipline jumped to the forefront in November 2021 in Babylon, when former students accused a dozen teachers of misconduct and blamed the district for mishandling the allegations. The New York State Attorney General's Office began an investigation.

WATCH: Confidential agreements made by LI school districts

Teacher firings are rare

Districts across Long Island award tenure to hundreds of fourth-year teachers and administrators each year, rewarding them with job protections that employment experts call the strongest of nearly any public-sector occupation. Among the advantages: School districts looking to discipline or dismiss a tenured teacher must follow a process laid out in state law that places a premium on confidentiality by protecting the educator’s reputation and shielding the alleged conduct.

For the Island's 35,000 public school teachers, terminations are rare. Long Island’s 124 districts have combined to fire an average of three tenured educators a year through the state's disciplinary process — commonly referred to in education circles as a "3020-a" — over the past decade.

The Process

3020-a: A public school district seeking to discipline or terminate a tenured teacher follows rules in state law commonly referred to as “3020-a,” its section title. First, districts confidentially file charges against the teacher with the state Department of Education. A hearing officer decides whether the district’s case meets the burden of proof, then determines the appropriate penalty.

Settlement Agreements: Often districts and the teacher negotiate discipline instead of going through a 3020-a proceeding. In these scenarios, school administrators and their lawyers meet with the teacher, their union representative and their attorney and reach an agreement on the discipline. The terms of these agreements typically are approved by boards of education. School districts are not required to detail the misconduct in the agreement.

Districts avoided bringing most cases to a state-appointed hearing officer because of the expense and having no control over the discipline. Schools paid law firms an average of about $108,300, according to a Newsday analysis of 20 such cases completed through the state's disciplinary process between 2018 and 2022.

School districts instead negotiated discipline and resignations directly with the teacher, their union and attorneys, outside of the state's hearing process. In these cases, districts either withdrew the disciplinary charges or reached a settlement agreement before filing charges. Legal expenses for settlements typically don't eclipse $10,000, school administrators and education law attorneys said.

Most of the settlements do not state the nature of the misconduct allegations. In those that do, the misconduct ranged from physical contact with students to theft of money to sexual harassment to showing inappropriate material to students in class. Typically, the umbrella phrase used is “conduct unbecoming a teacher.”

The state Education Department relies on a separate process to determine whether teachers and administrators are fit to stay in the classroom. And that process is slow.

New York law requires that superintendents report teachers who committed “an act that raises a reasonable question about the individual's moral character” to the state Education Department. Those reports trigger an investigation that could lead the state to revoke the teacher's certification.

In the past decade, the state revoked 43 Long Island educators’ licenses, some after they were convicted of felonies, and compelled another 61 to surrender theirs rather than face a hearing. The state Education Department declined to say why those 61 surrendered their licenses, citing privacy reasons.

State education officials confirmed that teachers under investigation can remain in the classroom during the yearslong effort to revoke their license.

51 times LI districts used 3020-a hearings to fire educators

33 resulted in terminations

A Newsday review of 20 cases since 2019 found that it took the state Education Department an average of nearly three years to take action on an educator's license — and, in one case, more than eight years.

The state Education Department in a statement attributed the lengthy delays to staffing issues, pandemic-induced scheduling disruptions and investigators' preference to wait until outside investigations, disciplinary hearings, civil litigation and criminal investigations are resolved before acting.

Betty Rosa, the state’s education commissioner, declined interview requests.

Roger Tilles represents Long Island on the state Board of Regents, which oversees the state Education Department. He doesn't recall the state's teacher discipline process ever being discussed by the Regents, but said it could come before them if it negatively impacts "how our kids are getting taught."

Mary O’Meara, superintendent of the Plainview-Old Bethpage district, said settlement agreements that lead to a teacher's resignation typically save districts money and often eliminate the need for students to testify about traumatic events under cross-examination before a hearing officer.

“Sometimes it's done for the dignity of the students or the other people involved,” she said.

While acknowledging that settlements allow the teacher to find work in another classroom until the state potentially takes action on their license, O’Meara said a district with a good human resources department would diligently check references and raise concerns about an “abrupt” stop in the prospective teacher’s past employment.

Andrew Pallotta, president of the state’s largest teachers union, New York State United Teachers, declined an interview request. NYSUT represents 250,000 teachers statewide.

NYSUT's website says: "Tenure, simply put, is a safeguard that protects good teachers from unfair firing."

“Ninety-nine percent of teachers will never deal with discipline, a settlement, or go through a 3020-a," said Scott O'Brien-Curcie, president of the Wyandanch Teachers Association, while referring to the state's disciplinary process by its section title in state law. "That's shown in the numbers, and it's clear."

We are failing our children, our profession and, of course, taxpayers.

— Dafny Irizarry, president of the Long Island Latino Teachers Association

Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

State law does not include any pension forfeiture provisions for public school teachers, said Tim Mack, New York State Teachers' Retirement System spokesman.

Using settlement agreements for discipline in many cases contradicts educators' duty “to protect the safety and well-being of our students and ensure their academic success,” said Dafny Irizarry, president of the Long Island Latino Teachers Association.

“By reaching agreements that might not hold school employees fully and fairly accountable for illegal, immoral or unethical acts," she added, "we are failing our children, our profession and, of course, taxpayers.”

State's discipline hearing is courtlike process

To dismiss a tenured educator, districts file a charge with the state, triggering a process that plays out like a court proceeding.

With a state-appointed hearing officer serving as the judge and jury, the district must prove its case and often will attempt to do so through exhibits and testimony of witnesses such as teachers, parents and sometimes even children. The hearing officer decides whether the district’s case met the burden of proof, then determines the appropriate penalty.

Administrators and attorneys for Long Island districts said schools view the state's disciplinary process as a last-resort because of the high expense of legal representation, the requirement to pay the suspended teacher, and that the outcome is difficult to predict.

In the past decade, Long Island districts combined to bring 51 cases to a hearing officer, seeking termination in all but one, according to records Newsday obtained from the state Education Department. Schools won the right to terminate the educator 33 times. The hearing officer issued a lesser penalty, such as an unpaid suspension, in the other cases.

It's impossible to know how many times the hearing officer ruled in favor of the teacher and dismissed all charges because state law calls for the records in those cases to be expunged.

The New York State School Boards Association, a group that advises school boards, encourages districts to consider negotiating settlements in most cases instead of the state’s discipline process “to avoid expensive, time-consuming and uncertain litigation.”

A 2018 statewide survey by the association found that cases typically lasted six months. The most recent 20 cases on Long Island took an average of 15 months to complete, according to a Newsday analysis.

“It is not in any way, shape or form a given that you are going to secure a termination in a 3020-a,” said Jay Worona, the school board association's deputy executive director and general counsel.

In New York, there has been a decadeslong statewide push to reform the disciplinary process. Changes to the law in 2015 sped the process to avoid long 3020-a cases, such as the four-year wait before Long Beach schools won the right to fire special education teacher Lisa Weitzman on charges of harming her severely disabled students, including pushing a student against a wall by his shoulders to restrain him.

During that time, the district paid Weitzman $650,000 in salary and benefits — teachers are placed on paid leave while the 3020-a case plays out — while also accumulating $320,000 in legal bills, district records show.

The legal bills charged to Long Island districts for 20 3020-a cases completed from 2018 through 2022 ranged from $13,195 to $475,600, records show. School administrators said there are other expenses associated with a 3020-a case, such as the salaries of the suspended teacher and their replacement.

Brentwood teacher Christopher Amato quits before hearing

Victims and their advocates said confidential settlements place a greater value on the teachers’ privacy and the district’s liability than support for the victims.

Caitlin Davidson, 27, said she feels “frustrated and sad” after the Brentwood district in November abandoned a case that sought the termination of a Brentwood High School biology teacher who Davidson alleges touched her inappropriately as a senior. Amato, 48, denied the allegations, said his attorney, Vess Mitev.

The district instead reached a settlement agreement with Amato that called for his resignation, with no explanation in the paperwork as to why he was willingly leaving his job. He resigned in December, midway through his 21st year with the district.

I just spent an entire year reliving the trauma ... he got to walk away with his license and a slap on the wrist ... .

— Caitlin Davidson, Brentwood alumna

Credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

“It feels like he got off,” Davidson said. “It feels like I just spent an entire year reliving the trauma over and over again, and at the end of it all, he got to walk away with his license and a slap on the wrist to go work somewhere else and potentially do this all over again.”

Davidson raised the allegations anonymously to the district in a letter sent in November 2021. She said that when she was a senior in 2013, Amato often sat her on his lap, kissed her neck, hugged her and touched her stomach and her bra line when they were alone in his classroom. She said the behavior stopped when he put his hand down the back side of her pants, underneath her underwear, and she said no.

In interviews with Newsday, Davidson said she was compelled to come forward eight years after those incidents because she saw a video of women making similar years-old accusations against teachers at a Babylon school board meeting.

A month after sending the anonymous letter, which led to Amato's suspension, she reported the allegations to Suffolk police. Dawn Schob, Suffolk County's police spokeswoman, confirmed detectives met with Davidson. Schob said they declined to pursue charges because the allegations were outside the two-year statute of limitations for a class A misdemeanor.

Veronique Valliere, an Allentown, Pennsylvania, psychologist, said it's common for teenage sexual abuse victims to wait years before reporting sexual abuse, often after statutes of limitations expired. Sexual abuse is among the most underreported crimes, especially among victims who know their abusers, she said.

"It takes years for them to really appreciate both because of experience and understanding, but also because of their cognitive and emotional development," she said. "It takes years to really appreciate issues like betrayal and exploitation and the need for adults to be caretakers."

Around the time Davidson met with Suffolk police, she also identified herself to the Brentwood district as the author of the anonymous letter and then worked with school district attorneys on their case seeking Amato's termination.

With the help of school district attorneys, Davidson said she dug up old emails and text messages between her and Amato.

Among the emails she discovered was one her mother, Susan Davidson, sent Amato in July 2013 in which she said, "I know what you did," "you have scarred her and she won't ever forget what you did," and "I only pray no one does such a thing to your daughter!" The email does not detail the allegations.

In a recent telephone interview, Susan Davidson said she sent the email because her daughter had just told her Amato put his hand down the back of her pants months earlier in his classroom. She said her daughter was emotional and defensive and made her promise not to tell police or the school.

"I was just fuming," she said. "I needed to do something."

Susan Davidson said she emailed Amato, without her daughter knowing, "to at least put it out to him that I know what you did, I know what you are and hope that that would at least stop him then from going further with anyone else."

Amato did not respond, Susan Davidson said. When questioned about the mom's email, Amato's attorney, Mitev, said: "None of this changes that this never happened, and we're sorry this is being discussed this many years later."

In addition to uncovering the emails and text exchanges, Caitlin Davidson practiced testifying with the school district's attorneys, preparing to tell the story before a hearing officer and facing cross-examination.

She said the preparation sessions stopped when the school district told her they were working on a settlement agreement. She said she learned the settlement's terms only after Newsday obtained the agreement from the district and showed her the document.

The deal also called for Amato to receive a $145,000 payout, representing six months' salary and his accrued unused personal and sick time.

That type of payout is common in resignation deals. Speaking generally, Saratoga Springs-based education law attorney Douglas Gerhardt called such payouts to teachers who agreed to resign “simply a business decision.”

“It’s prudent for the school district to say we’re going to pay the equivalent of six months’ pay for your resignation,” he said.

Also in the agreement: In exchange for Amato's resignation, the district withdrew the state disciplinary charges it filed and agreed “not to take any further legal action against Mr. Amato of any kind for any acts or omissions known or unknown from the beginning of time to the date of execution of this agreement.”

Our goal is to make sure the teacher never returns to the classroom. So we considered that a win.

— Brentwood Superintendent Richard Loeschner

Credit: Newsday/ Steve Pfost

Loeschner, Brentwood's superintendent, said he tries to avoid taking cases to a hearing that rely on victim testimony because that subjects them to a potentially traumatic experience being cross-examined by the teacher's attorney.

"Our goal is to make sure that teacher never returns to the classroom," he said. "So what happened was, we entered into an agreement, [and] they're never returning to the classroom here in Brentwood. So we considered that a win."

Asked why Amato resigned instead of defending himself before a hearing officer, his attorney, Mitev, said: "He is choosing to move on with his life rather than attempt to disprove false allegations in a bureaucratic process that is not fair to begin with."

Amato also resigned from his elected seat on the Hicksville school board.

Massapequa teacher Brian Merges banned from school

School attorneys said the biggest challenge to persuade a hearing officer to terminate a tenured teacher is compiling enough evidence.

The Massapequa district faced that obstacle in 2018 after an anonymous emailer alleged that a high school teacher had an inappropriate relationship with a female student two decades earlier while employed in a different Long Island district. Seven Massapequa administrators and psychologists and one retired school psychologist received the anonymous email, school records show.

An investigative report commissioned by the district, produced by an outside attorney and obtained by Newsday, provides a glimpse at the immediate steps the district took to compile proof necessary to proceed to a hearing:

- Massapequa administrators met with the teacher, Brian Merges, 58, of Lynbrook, and questioned him about the specifics that led to his departure from the Sewanhaka district in March 2003. Merges told the officials that he resigned after a mother complained about his online interactions with her daughter when she was a high school junior and senior. Merges said he resigned at the urging of then-Sewanhaka Superintendent George Goldstein “before it went public.” Goldstein, 80, told Newsday in a recent telephone interview that persuading a teacher to resign on the spot was a common method to get rid of troublesome teachers.

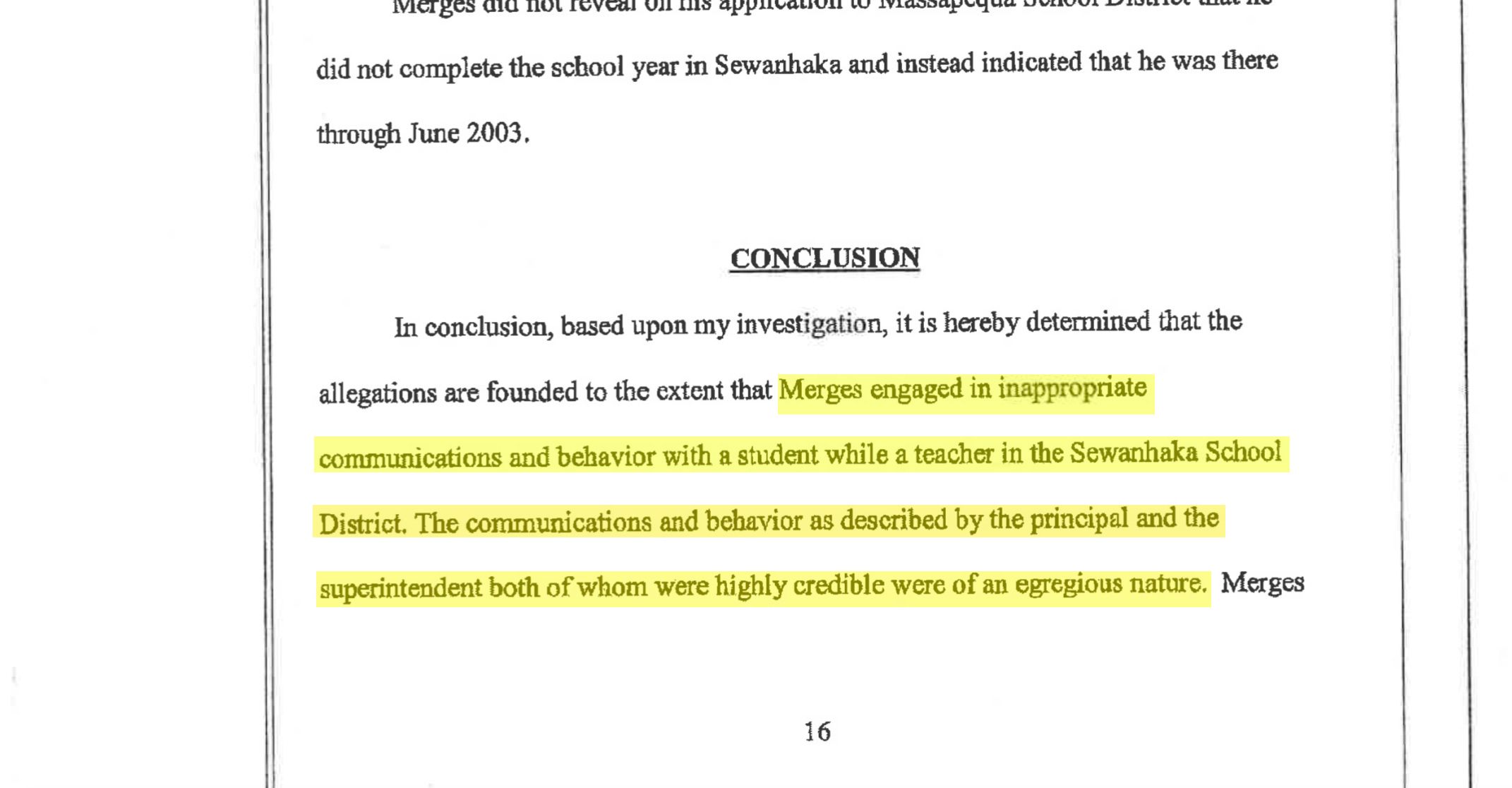

- The Massapequa school board hired an outside attorney, Bronwyn Black, to further investigate the circumstances surrounding Merges' departure from the Sewanhaka district. Following interviews with Merges and former Sewanhaka administrators, Black's 28-page report concluded “the allegations are founded that Merges engaged in inappropriate communications and behavior with a student while a teacher in the Sewanhaka School District.” Black did not respond to Newsday's requests for comment.

- Massapequa reported Merges to the state Education Department, potentially triggering an investigation that could revoke his license. His certification remains active, and the state Education Department declined to comment, citing privacy restrictions.

- Massapequa also contacted Nassau police, which declined to proceed because "they could not positively identify the possible victim," Black wrote. Nassau police declined to release records, also citing privacy restrictions.

Following Black’s investigative findings, Massapequa filed disciplinary charges with the state in June 2019 seeking his termination. The district and Merges settled the case three months later, before it reached a hearing officer.

The settlement terms were:

- He submitted a resignation letter that does not take effect until November 2023, which the New York State Teachers Retirement System said will be his 30th year of state education employment.

- The district assigned him to home as “curriculum specialist/teacher on special assignment,” at a reduced salary of about $62,000 per year.

- Merges agreed to surrender his teaching license when he resigns later this year.

- Merges “will not directly or indirectly teach, instruct, coach, or tutor any District students or any other persons under the age of 18 at any time.”

David Bloomfield, education law professor at Brooklyn College and The CUNY Graduate Center, reviewed the Massapequa documents that Newsday obtained. He commended Massapequa for securing an agreement that removed Merges from the classroom and contact with minors despite what he said would have been "a relatively weak case" before a hearing officer.

"What we're dealing with here is what I tell my students is legal land, not education land," Bloomfield said. "Given the lack of direct testimony either by the anonymous emailer or the victim and the amount of time that's lapsed, who knows how it's going to come out?"

Merges said his relationship with the high school student at Sewanhaka was not physical and he was not close with her, according to the investigative report. He said the relationship featured online conversations he described as "maybe they had gone past a certain point." He did not remember the substance of the conversations.

Massapequa school officials, Merges and Merges’ attorney, Matthew Weinick, declined to comment.

Elmont teacher Robert Russo's case takes seven years

State law requires superintendents to report to the state educators who commit an act of "questionable moral character."

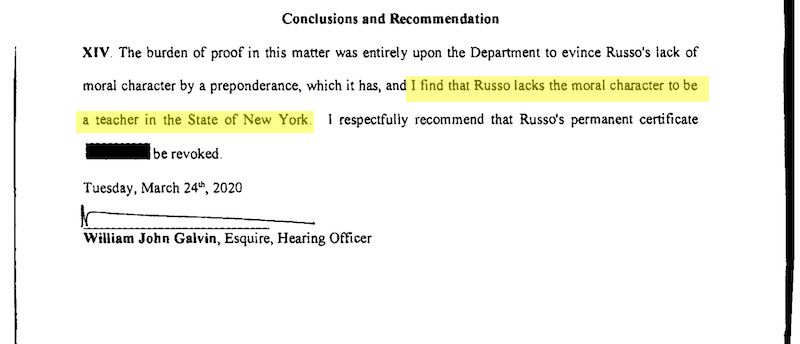

In one such case, the state revoked the license of former Elmont High School business teacher Robert Russo in 2020, seven years after the district reported him to the state, records show. He resigned from the district last year after the state denied his appeal.

The district reported Russo after a colleague spotted him giving a female student — a high school senior — a ride in his car after school in June 2013, against school rules. Russo then directed the student to lie about it under questioning by the principal, records show.

Fellow teachers and students also expressed concern about the personal nature of his relationship with the student, the records show.

The district, instead of proceeding with state disciplinary charges against Russo in 2013, reached a settlement that fined him $15,000, sent him to counseling and banned him from involvement in after-school activities for five years.

Russo remained in classrooms another four years until the state formally sought to revoke his license, district records show.

The subsequent state investigation, which looked back at Russo's interactions with the student, revealed 70,000 text messages and nearly 2,000 phone calls between them.

The district, after learning that the state sought to revoke Russo's certification, placed him on paid administrative leave in 2017 while the case moved forward.

Russo declined to comment.

"This case is a clear illustration of why school districts are required to report these types of matters to the state Education Department," said Deirdre Gilligan, a spokeswoman for the district's public relations agency, Syntax. She noted that state investigators "may then expand on the school district's investigation, which in some cases will lead to a different outcome."

Education law experts blamed the yearslong delays, such as in Russo's case, on a heavy caseload falling on a thin investigative staff.

The state Education Department's Office of School Personnel Review and Accountability has a staff of 21, a dozen of whom are investigators. In each of the last three years, the office took action against an average of 59 educators after sifting through 5,242 reports, the state said.

Notices about the arrest of a current school employee by a law enforcement agency within the state made up the majority of reports the state investigators dealt with, the state said.

Without providing specifics, the state Education Department said it is seeking funding to hire more staffers in this year's state budget.

Bart Zabin, a retired state investigator, said: “I can't speak to the backlogs other than to say, there have been problems. And I'm aware that there are significant backlogs. And this gets into all kinds of other conversations about resources and realities with regards to state employment and the priorities of departments and those kinds of things.”

Zabin said he was a staff of one when he started in the 1980s and that even as the staff grew, so did the reports calling for an investigation. He said it’s a difficult problem to solve without increasing the staff size significantly.

“I don't have a good answer for you,” he said. “It’s frustrating, and it’s problematic.”

Settlements rarely discussed publicly

On Long Island, school boards approve settlement agreements in public session. Critics said there is little that is actually public about that process.

School boards — local residents elected to oversee the district operations — vote in public meetings to approve settlements on agendas that do not name the employee or detail the agreement’s terms. Votes usually are unanimous. They rarely discuss the agreements in public. Instead, they deal with personnel matters such as discipline in executive sessions.

This is a modal window.

School board members do not discuss settlements to limit the district’s liability, protect the identity of the children impacted and because they are personnel issues, district administrators and attorneys said.

“It’s a balancing act,” said Greg Guercio, head of the Farmingdale-based law firm Guercio & Guercio, which represents 43 districts on Long Island.

“The school district has to balance its interests, the community’s interest in transparency with regard to its contractual obligations and with regard to its legal obligations that are addressed in the settlement document itself,” Guercio added.

Peter Brill, a Long Island attorney who represents teachers facing discipline, regularly argues on behalf of teacher rights. He noted that he's a parent, too, and believes there’s room for greater transparency with teacher discipline.

“As a parent, would I want more information about who’s teaching my kids? Of course,” Brill said.

Districts are within their rights to present as little information as possible about settlement agreements at school board meetings, according to Shoshanah Bewlay, executive director of the state’s Committee on Open Government.

She said the responsibility falls on citizens to request the agreement to see what the board approved, noting that state judges have determined that settlement agreements are considered public under state law.

“Making proactive disclosure a requirement in this context would, I imagine, be appreciated by all parents of public school students,” Bewlay said. “But such a requirement would necessitate a change in the law.”

Changes require state legislation

Nationwide, each state handles teacher discipline differently. Some states discourage schools from using settlement agreements for discipline. For example:

- Georgia requires schools to report to the state any violation of its teacher code of ethics, ranging from sexual and physical abuse of students to misusing district funds or lying about their reason for taking days off.

- Kentucky requires schools to report to the state the names of teachers who resign under the threat of dismissal to prevent them from landing in another classroom.

- Florida posts online a searchable database of teachers who negotiated settlements after charges were filed with the state.

In New York, the state Education Department said laws protect students — regardless of if the school disciplined a teacher via a settlement agreement.

State law mandates that teachers report to administrators any allegation of sexual misconduct or physical abuse involving a student, and superintendents are required to inform law enforcement if “reasonable suspicion exists.”

Schools also are barred by state law from allowing a teacher to resign in exchange for withholding from law enforcement or the state Education Department allegations of physical abuse, reckless behavior, sexual misconduct or giving indecent material to minors.

These laws aim to protect children in the classroom while preventing schools from covering up egregious misconduct.

“What I have noticed over the years is that if there’s not a specific consequence for a school district to use a settlement agreement, it’s just too easy a way out of a very sticky problem,” said Phillip Rogers, executive director of National Association of State Directors of Teacher Education and Certification, an education department advisory group.

“If you were to present this notion in front of a dozen parents, I doubt they would say, ‘Yeah, I kind of like that idea,’ ” he said.

There is no shortage of ideas on how to improve the state's teacher discipline system.

The New York State School Boards Association wants the state to authorize districts to terminate tenured teachers without a formal hearing if they have had their license revoked or been convicted of child abuse in an education setting.

“Taxpayers shouldn’t have to go through a due process hearing to figure out whether those things should cost somebody their job,” said Worona, the state school boards association's deputy executive director and general counsel. “Obviously, a person who’s not certified shouldn’t be in a position to be teaching students, [and] someone who abuses students shouldn’t be in a position to teach.”

Safeguarding a teacher’s ... privacy is not more important than protecting a child’s safety.

— Laura Ahearn, executive director of Crime Victims Center

Credit: Morgan Campbell

Laura Ahearn, the executive director of the Ronkonkoma-based Crime Victims Center, wants lawmakers to bar schools from using settlements to discipline “abusive teachers when probable cause and credible evidence exists” and provide victims with “a no-cost attorney advocate to represent their interests.”

She said victims need more support and guidance when they speak up about teachers.

"Safeguarding a teacher’s or school employee’s privacy is not more important than protecting a child’s safety," Ahearn said.

Legislation is required to enact any of these changes.

Any proposal to amend the 3020-a state law would impact the rights of teachers and therefore draw the ire of their union, a powerful lobbyist in state politics, a state lawmaker said.

Assemb. Michael Fitzpatrick (R-St. James) said the teachers union likes the state’s disciplinary system as is because the system “has over the years developed into a very expensive process that serves to protect jobs.”

NYSUT spokesman Ben Amey defended their lobbying efforts, saying educators "deserve a voice in workplace policies."

Amey said the teachers union believes the state's current disciplinary process is effective.

“We support both due process for those facing discipline and accountability for misconduct," Amey said. "Under state law, which allows for either a two-party settlement or a full 3020-a process, both things are achievable.”

Victims advocate Ahearn disagreed.

"There is a tsunami of power behind a lot of teachers and it's the teachers union," Ahearn said. "Parents and students need more power."

Credits

Reporters: Jim Baumbach, Joie Tyrrell

Additional reporting: Dandan Zou, Michael Ebert and Arielle Martinez

Editors: Don Hudson, Keith Herbert

Photo editor: John Keating

Video editor: Jeffrey Basinger

Videographers and photographers: Jeffrey Basinger, Thomas A. Ferrara, Alejandra Villa Loarca, Drew Singh, Steve Pfost, Howie Schnapp, Chris Ware

Video producers: Artie Mochi, Jim Baumbach, Jeffrey Basinger, Robert Cassidy, John Keating

Multimedia Journalist: Ken Buffa

Copy editing: Mark Tyrrell, Estelle Lander, Doug Dutton

Additional research: Caroline Curtin, Laura Mann, Judy Weinberg

Project manager: Tara Conry

Digital design: James Stewart

Social media: Priscilla Korb

Quality Assurance : Daryl Becker

Print design: Jessica Asbury

Tagging sharks off LI ... Animatronic dinosaur exhibit ... What's up on LI ... Get the latest news and more great videos at NewsdayTV