'Sidney Lumet: A Life': Smart director, smart bio

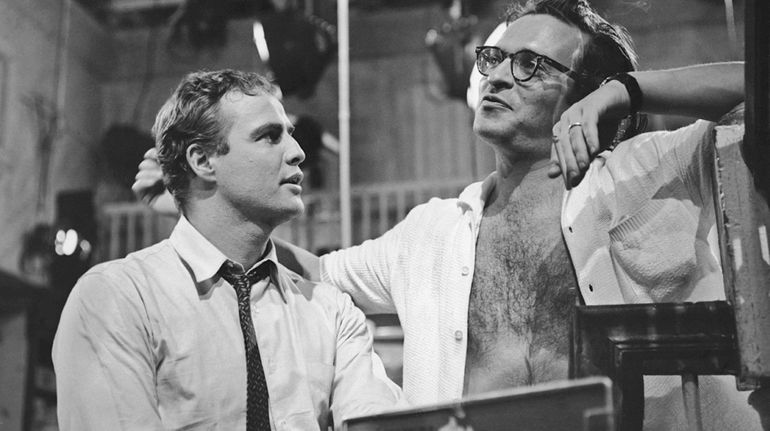

Marlon Brando and director Sidney Lumet on the set of the 1960 film "The Fugitive Kind." Credit: Archive Photos / Stringer / Getty Images

SIDNEY LUMET: A LIFE by Maura Spiegel (St. Martin's Press, 416 pp., $29.99)

With the exception of Woody Allen, there’s probably no other filmmaker who shared such an affinity for New York — both city and state — as Sidney Lumet did. Manhattan played a key role in his auspicious first feature, 1957’s “12 Angry Men,” and his last, “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead” (2007), while East Hampton, where Lumet had a home, served as the setting for “Deathtrap” in 1981.

The director’s body of work and his gift for presenting New York stories are examined in scrupulous detail by Maura Spiegel in her insightful and entertaining biography “Sidney Lumet: A Life.” Drawing from source material including Lumet’s unfinished, unpublished memoir and interviews with friends, colleagues, family members, even ex-wives, Spiegel paints a rounded portrait of her subject. Her admiration for Lumet is apparent throughout.

Only 25¢ for 5 months

With the exception of Woody Allen, there’s probably no other filmmaker who shared such an affinity for New York — both city and state — as Sidney Lumet did. Manhattan played a key role in his auspicious first feature, 1957’s “12 Angry Men,” and his last, “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead” (2007), while East Hampton, where Lumet had a home, served as the setting for “Deathtrap” in 1981.

The director’s body of work and his gift for presenting New York stories are examined in scrupulous detail by Maura Spiegel in her insightful and entertaining biography “Sidney Lumet: A Life.” Drawing from source material including Lumet’s unfinished, unpublished memoir and interviews with friends, colleagues, family members, even ex-wives, Spiegel paints a rounded portrait of her subject. Her admiration for Lumet is apparent throughout.

Spiegel starts with Lumet’s upbringing, which was anything but conventional. From the time Sidney could walk, he was performing on stage at the Yiddish Theater with his father, Baruch Lumet, a well-known entertainer whose heyday was pretty much over by the late 1930s. It then fell on Sidney to become the family breadwinner thanks to roles on Broadway, starting with “Dead End” in 1935, and radio. “When I worked, we ate,” Lumet recalled years later. He also honed his craft as part of the Group Theatre, a precursor to the Actor’s Studio, attending its summer camp at Lake Grove in the summer of 1939.

While he felt at home in the theater, Lumet’s home life was far more troubling. His mother, Eugenia, suffered from depression and died during childbirth in 1940. His relationship with his demanding father was strained, a situation exacerbated by Sidney consulting with a lawyer to protect his dad from touching his earnings. When he was in the Army, Lumet sent his checks to his sister, Faye, whom he became estranged from later on after she suffered a mental breakdown. The Army stint also left him emotionally scarred from the bullying and humiliation he faced as a result of anti-Semitism. Lumet recalled the experiences when he attempted to pen his memoir in the 1990s, but according to his first wife, actress Rita Gam, Lumet never spoke to her of his Army years..

Returning from the war, Lumet attempted to resume with acting, but after being cut from the Actors Studio, he ventured on a different path. Through pal Yul Brynner, he carved a new career directing for television, where he immediately earned a reputation for his ability guiding his actors. ‘ “If he said, ‘I’d like you to lie down in the road and then the truck is going to drive over you,’ you’d just ask, ‘How do you want me to position my body?”,’ actor Tab Hunter told Spiegel.

Lumet’s TV work so impressed Henry Fonda, star and co-producer of “12 Angry Men,” that he hired him to direct the courtroom drama. Lumet’s attention to detail from finding the right cameraman to “getting the ‘sweat right’ for each of the characters” was apparent from the start. The film ended up getting a best picture Oscar nomination and earned Lumet the first of five nods for best director (he never won but did receive honorary Oscar in 2005, six years before his death).

Though Spiegel deals with Lumet’s four marriages, those craving gossipy details will likely be disappointed. Of his marriage to heiress Gloria Vanderbilt, wife No. 2, we learn that he would leave her romantic notes every morning before heading to the set. The marriage ultimately failed, Vanderbilt said, because her own acting ambition became a destructive force in their relationship, but they remained lifelong friends.

Whether Lumet had affairs with his leading ladies is barely hinted at. Spiegel writes that while filming “That Kind of Woman” with Hunter and Sophia Loren in 1959, Lumet later admitted to “having fallen in love with Sophia.” No further details are provided.

Lumet’s experience with divorce served him well when filming a pivotal scene in “Network” in which William Holden tells wife Beatrice Straight that he’s in love with another woman. Lumet put extra care into the scene to make it all about Straight’s reactions. She only had five minutes on camera, but still picked up a best supporting actress Oscar and set a record for the briefest screen performance of any winner.

While making “Network,” Lumet’s third marriage was unraveling but he found refuge in East Hampton, where he’d spend many a weekend just sleeping or watching football. It wasn’t until his fourth marriage — to Mary Bailey Gimbel, ex-wife of department store magnate Peter Gimbel — that Lumet finally found his perfect soul mate.

Spiegel does a neat balancing act of getting readers to know about Lumet the man and Lumet the filmmaker. And after reading her bio, you’re sure to develop a richer appreciation of his screen legacy.