Brooklyn Academy of Music's big birthday & theaters' big rebirths

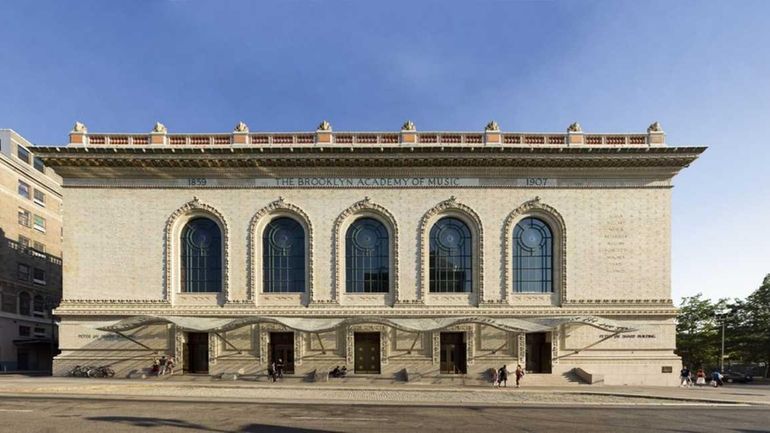

[object Object] Credit: Peter Mauss/ESTO Photo (BAM), the oldest performing arts center in the US, celebrates its 150th anniversary with special events on visual arts and theatre shows in 2011.

Live theater is both prized and underestimated for its here-and-gone shelf life. The moment a play appears, literally, it is in the process of disappearing. Broadway shows, except for the rare long-running smash, are put together for the individual production, then dismantled and scattered, clearing the theater so another show can move in.

So I am struck -- impressed, really -- by the message of continuity in so many big anniversaries and building projects this season. Oh, sure, anniversaries are often used by arts groups when they need a publicity angle, a hook on which to hang an attention-craving banner in an overstimulated marketplace.

Only 25¢ for 5 months

Live theater is both prized and underestimated for its here-and-gone shelf life. The moment a play appears, literally, it is in the process of disappearing. Broadway shows, except for the rare long-running smash, are put together for the individual production, then dismantled and scattered, clearing the theater so another show can move in.

So I am struck -- impressed, really -- by the message of continuity in so many big anniversaries and building projects this season. Oh, sure, anniversaries are often used by arts groups when they need a publicity angle, a hook on which to hang an attention-craving banner in an overstimulated marketplace.

But look at this. The Brooklyn Academy of Music just began celebrating its 150th with a schedule of staggering ambition and variety. The long-struggling but legendary La MaMa theater is turning 50 with a family-friendly street party next Sunday followed by a starry gala of alums (Sam Shepard, Wallace Shawn, Harvey Fierstein) and an adventurous major lineup.

In both cases, these institutions did not just create and present events. Along the way, they each defined a chunk of unloved real estate -- Fort Greene in Brooklyn, Fourth Street in the East Village -- that, over the years, became a high-end magnet and thriving cultural community.

This season also includes a related phenomenon that should give theater people an unfamiliar sense of security. Theaters are being built and others are being heavily renovated at a time when nobody is supposed to afford any so-called shovel-ready projects.

The New York City Center, which opened for the performing arts 68 years ago with Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia pretending to conduct the New York Philharmonic, kicks off its newly refurbished life of much-expanded programming with an Oct. 25 gala, where Mayor Michael Bloomberg will wave a baton.

In February, the Signature Theatre Company, the invaluable Off-Broadway institution that focuses on a single playwright each season, is moving two blocks east to its new multispace Frank Gehry-designed complex. In addition to dedicating this year to the work of Athol Fugard, James Houghton's 20-year-old treasure has initiated a "legacy" project with world premieres by prior honorees (this year, Edward Albee), plus a new annual program to support five new and midcareer playwrights with money and, hallelujah, full health benefits.

"We have been building toward this moment for more than a decade," Houghton says. "And despite the state of the economy, we have found that it has captured the imaginations of a broad spectrum of people, from artists to the funding community, who are eager to get onboard and help us take this exciting next step."

And the overachieving Atlantic Theater Company, which has been itinerant for more than a year, returns this spring to a modernized version of its 1854 theater-in-a-church. The first play will probably be John Patrick Shanley's "Sleeping Demon," the third in the trilogy that began with the Pulitzer Prize-winning "Doubt." Chelsea was far from a boomtown when David Mamet and his buddies opened the Atlantic in 1985.

"We're in the final push to reach the revised goal," says Jeffory Lawson, Atlantic's managing director, who explains that the economy and delays in early construction sent the original $7.5-million goal up to $8.3 million. The theater's board and various city agencies have brought them to $6.1 million, "but these last dollars are the hardest to raise."

Although not scheduled to open until spring 2013, a major new Brooklyn home is being built (co-funded by the city) for the Theatre for a New Audience as part of what has been rightfully designated the BAM Cultural District. The troupe, one of the city's most reliable and adventurous Shakespeare producers, has been renting and free-floating since Jeffrey Horowitz began in 1979. Julie Taymor, who directed her first Shakespeare with the company, will stage the inaugural production.

Not all urban renewal has been terrific for all deserving theater. I worry about the fate of St. Ann's Warehouse, a priceless haven for unpredictability and adventure in DUMBO. Chances are, the wasteland under the Brooklyn Bridge would not be marketing its hot and funny name if St. Ann's had not been bringing New Yorkers to 38 Water St. for the past 10 years. But Susan Feldman's internationally acclaimed institution will be reclaimed by developers in May and plans to move across the street to the old Tobacco Warehouse have been opposed by civic groups that want to keep it for an open neighborhood site.

Meanwhile, not far away, BAM is celebrating its 150th with a big book, a new building and an enormous series that, for starters, includes four November performances of John Malkovich in "The Infernal Comedy: Confessions of a Serial Killer." There is even going to be a special beer for the festival year, adorably called BAM Boozle.

So happy anniversary to BAM and La MaMa, and to the Group Theatre (80th), the Soho Rep (35th), League of Professional Theatre Women (30th) and the Music-Theatre Group (40th). And happy 70th birthday to Robert Wilson, the vanguard's immortal young turk, whose Watermill Center on Long Island will be turning 20.

Last month, Rocco Landesman, chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, announced an imaginative national program meant to use culture to energize 34 failing neighborhoods and buildings. Clearly, he is onto something. He has rallied a bushel of foundations, corporations and federal agencies (including departments of Housing and Urban Development, even agriculture and transportation) for a program called ArtPlace.

The endowment, somehow still breathing after decades of malignant neglect, calls the approach "creative place-making." The agency says it's been promoting it for 20 years. May this be a happy anniversary, too.