‘Escape to the Great Dismal Swamp’ review: Fascinating, well-told story

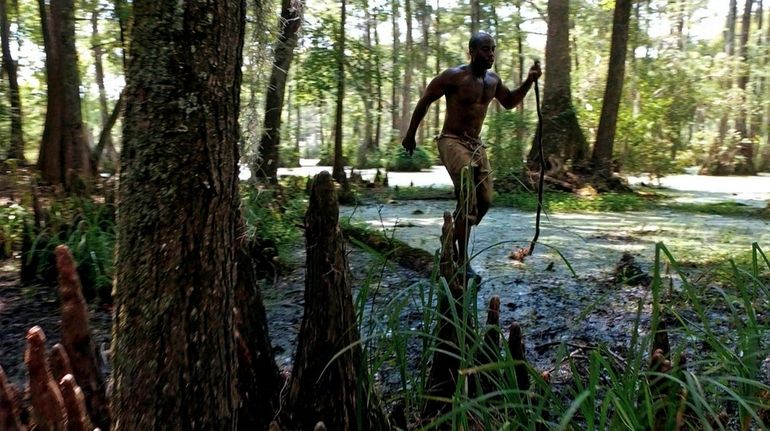

From the Smithsonian Channel's documentary "Escape to the Great Dismal Swamp" Credit: Smithsonian Channel

DOCUMENTARY “Escape to the Great Dismal Swamp”

WHEN | WHERE Monday at 8 p.m. on Smithsonian Channel

WHAT IT’S ABOUT The Great Dismal Swamp, now a national wildlife refuge, lies on the border of North Carolina with Virginia, and extends south from Norfolk. Thousands of escaped slaves fled here from the earliest Colonial times. These so-called “maroons” — the name for any escaped slaves who fled into the wilderness and who often lived with indigenous peoples — avoided capture because the swamp was vast and trackless (and parts still are).

“Escape” tells the story of what’s called the Great Dismal Swamp Landscape Study begun by American University historical archaeologist Dan Sayers in 2002. “Escape” follows Sayers, along with associate Becca Peixotto, deep in the swamp in various sites where he’s found ample evidence of human habitation precisely dated through the use of optically stimulated luminescence, or OSL. One instance shown here dates the remains of a maroon house to having been built between 1670 and 1690.

Only 25¢ for 5 months

WHAT IT’S ABOUT The Great Dismal Swamp, now a national wildlife refuge, lies on the border of North Carolina with Virginia, and extends south from Norfolk. Thousands of escaped slaves fled here from the earliest Colonial times. These so-called “maroons” — the name for any escaped slaves who fled into the wilderness and who often lived with indigenous peoples — avoided capture because the swamp was vast and trackless (and parts still are).

“Escape” tells the story of what’s called the Great Dismal Swamp Landscape Study begun by American University historical archaeologist Dan Sayers in 2002. “Escape” follows Sayers, along with associate Becca Peixotto, deep in the swamp in various sites where he’s found ample evidence of human habitation precisely dated through the use of optically stimulated luminescence, or OSL. One instance shown here dates the remains of a maroon house to having been built between 1670 and 1690.

MY SAY As good as this is, “Dismal Swamp” requires just the slightest bit of research on the part of viewers before tuning in. So type “Dismal Swamp” into your browser’s address field, then go to the Google Earth view. There, in the vast, undifferentiated swath of green — which was far more vast in Colonial times — is the hidden history of a hidden people. Thousands lived there for generations and for centuries, from 1650 to the end of the Civil War. Some, perhaps many, lived their entire lives there. This was an island of freedom for all of them.

There are many stories lost to African-American history — far too many — but this surely has to be among the most remarkable of them. Mary Elliott, of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, says of these hidden lives that “they inform us about this larger American experience [and] the African-American story is the American story.” That’s exactly right, which is why a program like this needs to be seen. TV can at least begin to fill in the blanks.

Beginning with the title, there’s also something unexpectedly poignant about “Escape to the Great Dismal Swamp.” As Sayers and Peixotto sift mounds of red dirt, every now and then a small rock turns up — evidence of human habitation because rocks of any size don’t occur here naturally. He finds a fraction of a clay pipe dating from the 1600s. Someone was smoking this when it fell through the cracks of a floorboard. As archaeologists are wont, they extrapolate whole lives and entire settlements from these fragments. Sayers believed the maroons lived everywhere, or on any piece of dry land: “Every island in the swamp was hot property,” he says.

What these two surmise, however, is that these lives were far from helpless. The maroons created barricades with watch towers. They had access to guns. They chipped arrowheads for hunting. Their homes were sturdy. They knew escape routes and secret byways, a reason so many evaded capture over 2 1⁄2 centuries of slavery.

“Escape” can’t possibly begin to tell even a fraction of this story, but it does offer the contours, and there’s something heroic, even inspirational, in those. Elliott puts it this way: As a maroon, “you were doing it on your own terms and in a place providing you freedom.”

BOTTOM LINE A fascinating and well-told story of a lost — and important — chapter of African-American history.