Parrish art exhibit is all about Frida Kahlo

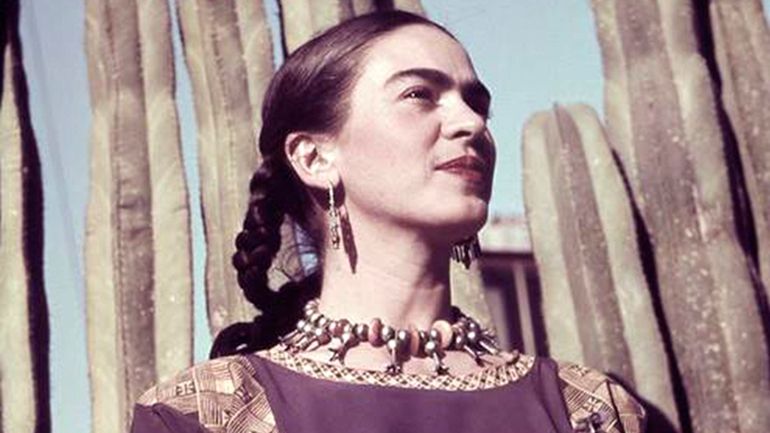

"Frida in San Angel," 1940 by Ivan Dmitric is from Cristina Kahlo-Alcala's collection of family photographs. Credit: Collection of Cristina Kahlo/Ivan Dmitric

She's arguably the most famous woman artist in the world. According to Google search results, the great Mexican painter Frida Kahlo tops even Georgia O'Keeffe, with more than 40 million hits. Few artists have captured hearts and imaginations as much as Frida Kahlo, and you can connect with her in a completely new way at the Parrish Art Museum's "Kahlo: An Expanded Body" exhibit through April 2.

Kahlo has been the subject of movies, books, plays, songs, immersive experiences, emoji, countless exhibitions, and an upcoming Broadway musical. Her crown of braids and unibrow are instantly recognizable and appear on everything from coffee mugs to sneakers. Fridamania, as it's been affectionately called, is an expression of support for a woman who triumphed over adversity, challenged patriarchal norms, championed underdogs and unabashedly painted her truth. But do the millions who love her really know Frida Kahlo? Not enough, the exhibition and its curators suggest.

Only 25¢ for 5 months

She's arguably the most famous woman artist in the world. According to Google search results, the great Mexican painter Frida Kahlo tops even Georgia O'Keeffe, with more than 40 million hits. Few artists have captured hearts and imaginations as much as Frida Kahlo, and you can connect with her in a completely new way at the Parrish Art Museum's "Kahlo: An Expanded Body" exhibit through April 2.

Kahlo has been the subject of movies, books, plays, songs, immersive experiences, emoji, countless exhibitions, and an upcoming Broadway musical. Her crown of braids and unibrow are instantly recognizable and appear on everything from coffee mugs to sneakers. Fridamania, as it's been affectionately called, is an expression of support for a woman who triumphed over adversity, challenged patriarchal norms, championed underdogs and unabashedly painted her truth. But do the millions who love her really know Frida Kahlo? Not enough, the exhibition and its curators suggest.

"Frida in the Armchair," front row, left, as photographed by her father, Guillermo Kahlo, ca. 1911. Credit: Collection of Cristina Kahlo/Guillermo Kahlo

HER PRIVATE SIDE

Mónica Ramírez-Montagut, the museum's executive director, along with co-curator Cristina Kahlo-Alcala, the grandniece of Frida Kahlo, want to introduce Kahlo's private side. "She has become like a movie character," said Kahlo-Alcala, "but she was a real person. That was really important to me — to show she's not an image. She was a real person, in a real body."

More than 100 rare photographs, documents and works of art, including two by Frida Kahlo, give an intimate glimpse into her short, fraught life. With family photos, personal letters (some with lipstick kisses still visible) and medical records, it's like looking through a family album, said Ramírez-Montagut.

WHAT "Kahlo: An Expanded Body" through April 2

WHEN | WHERE 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Monday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday and 11 a.m.-8 p.m., Friday, Parrish Art Museum, 279 Montauk Hwy., Water Mill

INFO $16, $12 seniors, free ages 18 and younger and college students with ID; 631-283-2118, parrishart.org

The focus on the body is deliberate and revelatory. Kahlo, who was from an artistic family, overcame childhood polio and planned to enter medical school in Mexico City. In 1925, at age 18, she was riding a bus that collided with a trolley. The accident injured everyone onboard, but none more than Kahlo, who was bedridden for months. During that period, her mother affixed a mirror to the recovery bed and her father lent her paints. The rest is art history. She painted herself, her surroundings, her caregivers, or as she stated, "I painted my own reality."

"Cristina Kahlo and Frida Kahlo" shows the artist, right, and her sister, the grandmother of exhibit co-curator Cristina Kahlo-Alcala. Credit: Collection of Cristina Kahlo/PETER RIESETT

Despite everything, Kahlo was irrepressible, indomitable, truthful, brave and adventurous. She experimented with gender roles, befriended and loved artists, actors and politicians, and married, divorced and remarried Mexico's then most famous artist, Diego Rivera. Was it her life or her art that made her an icon? "I think in the beginning it was her life," said her grandniece. "Now, I think people are discovering Frida Kahlo as a real artist."

Hearts, wounds, blood, and body parts all find expression in Kahlo's paintings, and are referenced in the show. A recreation of her mirrored bed invites visitors to experience how Kahlo painted during her recuperation. "The biological body and the metaphors that Frida created through her body of love and suffering are interwoven in this exhibition," noted Ramírez-Montagut. Also on view are contemporary works, some by Kahlo-Alcala, an artist herself.

Photographs of Frida Kahlo, some never exhibited before, along with contemporary artworks, documents, and personal letters are on view in the Parrish Art Museum's "Kahlo: An Expanded Body" through April 23. Credit: Parrish Art Museum/JENNY GORMAN

A PIONEERING FIGURE

In her 47 years, Frida Kahlo underwent more than 30 surgeries to repair injuries. Several are documented in the show, including one in which part of her leg was amputated. She was a woman who faced financial insecurity, divorce and even existential uncertainty. She was a self-taught painter who, like Vincent van Gogh, became more famous than the most revered artists of her time. Kahlo's friendships and romances with famous men and women, her donning of men's clothes and indigenous dress, and her overcoming unimaginable physical challenges and creating a unique and deeply moving body of work made her a hero for women, Latinos, the LGBTQ+ community, and artists and art lovers across the globe.

"She would be very proud to know that she was such a pioneer for women and others who fight for their ideals and for their own life," said Kahlo-Alcala.

"I think she was just unapologetically who she was. She took the opportunity to live her life at her fullest," said Ramírez-Montagut. "A lot of what we have shows the last stages of her life. Even in her last year, after all the suffering and all this pain, her advice to us in her last painting of beautiful, colorful watermelons, titled 'Viva la Vida,' is just 'go and live life.' I find that incredibly moving and admirable." She added, "Her life was authentic, and this exhibition is also remarkably authentic."