She didn't have an open-door policy

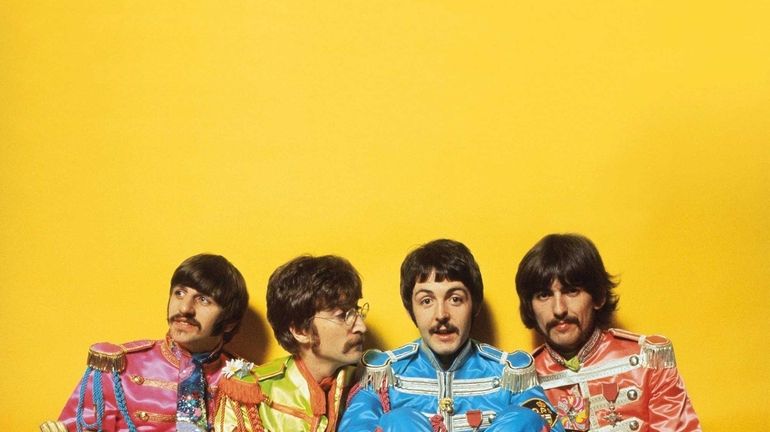

One of the rare outtakes of The Beatles from the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band session. Credit: AP

My dad took the door off my room the year The Beatles broke up.

White on one side, hot pink on the other, a hollow plywood door kept away the world of my family, and kept safe an entire world within.

Only 25¢ for 5 months

My dad took the door off my room the year The Beatles broke up.

White on one side, hot pink on the other, a hollow plywood door kept away the world of my family, and kept safe an entire world within.

When closed, it sealed off and defined a rectangular space, perhaps nine paces to the left, about 12 straight ahead. It protected hundreds of photos of The Beatles, cellophane-taped to the walls and ceiling; a poster of a waterfall that came alive under a black light; Jon Gnagy charcoals with a kneaded eraser; and a complete set of Beethoven's piano sonatas: Deutsche Grammophon recordings that I had signed out of the Deer Park Public Library immediately after they were acquired. Virgin vinyl, played unceasingly and renewed regularly.

When Ludwig was not at full volume, the aural space was filled with David Bowie, Black Sabbath or Carole King.

From the other side of the door came muffled sounds of Batman and Robin and the evening news on TV. Phones ringing. Talking. Shouting. My door assured me that if I were out of sight and out of earshot, I could ignore it all, and I might not have to do the dishes.

Most of all, by preventing speech entirely, words -- mine or theirs -- could not be misconstrued. It shielded me from verbal assaults and dissuaded me from preaching about the war in Vietnam, student strikes or racial politics.

Until, that is, the door was no more.

One night, after shouts up the stairs (once again, unheard over the music) and threats over several months of "We're taking the door off" went unheeded, I became aware of a pounding that was not from side two of "Abbey Road." Sitting cross-legged on the floor with a book, I had just reached to turn down the stereo when the door opened. Flung open. Hit the wall loud and hard and bounced open.

I looked up to a tsunami of red faces and waving arms; Dad, Mom, nearly indistinguishable in the mayhem. I didn't call 911. I didn't run away. Instead, I took revenge by aiming the speakers at the gaping hole and day after day turning the stereo to full volume. Not with Beethoven, but -- The Doors. Specifically, the precise segment with Jim Morrison shrieking: "You cannot petition the Lord with prayer!"

By clicking the repeat button, an endlessly profane parade was propelled down the stairs. By the time I fetched a hammer and calmly put the door back on its hinges a week later, my father pretended not to notice. (Because I was the oldest child, he had taught me how to use basic tools.) And the house, once again, grew quiet.

Now, that's not entirely the end of it. My dad, at my mother's insistence, tried this stunt a few more times, with a little less drama, and I put the door back again and again until I was so good with a hammer and a hinge that, within 15 minutes, normalcy would be restored. And the TV downstairs, with its droning dullness, and my family's conversation, by turns provocative and banal, were again kept at bay.

My mother for years would regale their "door off" moxie to friends and relatives, my father looking on as I raised a disdainful eyebrow at their antics, swallowing the humiliation. Occasionally, I pretended I was adopted.

Today, at my parents' Deer Park house, a sleek, flat-screen TV has replaced the old bulky Zenith in the family room. The chairs and sofa are arranged as they were before, facing the TV.

Upstairs, the door of my old room is on its hinges, always open, the same old '60s door with a cheap builder's knob; the hot pink side long since repainted white.

I never shut that door anymore. Now, when I visit, I stay on the ground floor and watch TV, bored as before but without complaints. There are no more political arguments. I sit in silence or make small talk. My mother is gone and my father sits quietly in a wheelchair in front of the television set, his main companion now. Occasionally, he turns to look at me, and he smiles, a smile that says he is glad I am there.

I never bring up the door.

My father, in a raspy voice, urges me to stay over in my old room, behind the door, where he remembers me as a child. I do not. I cannot. And when it comes time to go home, I close the front door, gently now, knowing he will be waiting for it to open again.

Ruth Bonapace, Leonia, N.J.

Submissions to My Turn and Let Us Hear From You must be the writer's original work. Email act2@newsday.com, or write to Act 2 Editor, Newsday Newsroom, 235 Pinelawn Rd., Melville, NY 11747. Include your name, address and phone numbers. Stories will be edited, become property of Newsday and may be republished in any format.