Secrets of the Montauk Lighthouse

Only 25¢ for 5 months

Civil War divides

Credit: Tara Conry

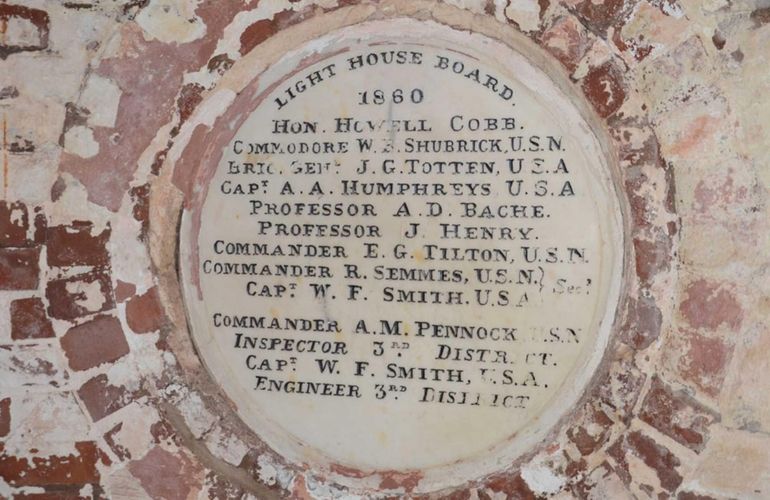

As you climb the 137 iron steps to the top of the lighthouse, look for a large, circular plaque on the wall about halfway up. It contains the names of the members of the U.S. Light House Board in 1860, when the structure underwent a major renovation. (At the time, the board managed lighthouses throughout the country.) What most don't know is that after the Civil War broke out one year later, four of those people -- A.A. Humphreys, J.G. Totten, Howell Cobb and R. Semmes -- served as military leaders on opposing sides of the war. Humphreys and Totten became Union generals, while Cobb and Semmes served as a Confederate general and admiral, respectively.

The fire tower

Credit: Tara Conry

That tall tower that stands near the lighthouse is now a storage facility, but during World War II the Army built it to serve as a lookout post. The tower, built with splinter-proof concrete, was equipped with radar and scanned the seas looking for German submarines. If the crew working inside the tower had spotted something suspicious, it would have communicated the coordinates to the troops stationed at nearby Camp Hero, who would have been ready to fire.

Target practice

Credit: Tara Conry

Another remnant from the lighthouse's World War II days is a small wooden barricade located on the property. Get up close and you'll notice the decaying wood is littered with holes -- bullet holes. It was used for target practice by the 30 or so soldiers who were stationed there in a barracks that was torn down in the late 1940s. Look hard enough and you may even find bullet fragments embedded in the wood.

A much lighter lens

Credit: Tara Conry

The current lens weighs 57 pounds, but the one used from 1903 to 1987 weighed 5,000 pounds, about the same as an adult male rhinoceros.

Abigail the Ghost

Credit: Tara Conry

When Henry Osmers, the Montauk Lighthouse historian, started working at the lighthouse, he learned about the legend of Abigail the Ghost. She was believed to be the lone survivor of a shipwreck that occurred in Montauk in the 1800s. But Osmers said he became a believer when he experienced not one or two but three encounters with the spirit. One time, while working in the attic, he said he felt the spirit repeatedly tug on his shirt. Over the years, he and other lighthouse staff have experienced odd occurrences – from strange noises and swinging pictures to furniture being moved in the middle of the night. When they can’t find a logical explanation for the incident, they chalk it up to Abigail.

T.R.'s tour

Credit: Tara Conry

Teddy Roosevelt paid a visit to the lighthouse on Sept. 6, 1898, after serving in the Spanish-American War. Roosevelt and his Rough Riders were stationed at a Camp Wikoff about four miles away. He got a tour of museum, climbed the tower and signed the guestbook, which is now on display at the East Hampton Library.

A side business

Credit: Tara Conry

Before the Army and later the Coast Guard operated the lighthouse, civilian caretakers ran the show. Living and working at the remote location could be a lonely life, but some of these keepers found a way to attract companions while earning extra cash. For instance, the caretaker in 1837, Patrick Gould, convinced the agency that managed the country’s lighthouses at the time, to build an extension to this building, which still sits on the property, so he could store extra supplies and equipment. Instead, he used the new space to take in overnight guests, charging $3 to $4 per night. This practice went on for 20 years until the U.S. Light House Board sent a letter to then-caretaker William Gardiner, chiding him that he was hired to be a “lighthouse keeper, not an inn keeper.” Oh, and he should “stop dispensing intoxicating liquors,” too.

Bunker on the beach

Credit: Tara Conry

Strolling along the rock wall that protects the lighthouse from the ocean, its hard to miss the large, black structure that rests on the beach nearby. Its a bunker left over from World War II. The bunker had been built into the bluff above, but over the years, erosion caused it to be exposed. By the 1970s the Coast Guard, fearing that the unstable structure could injure someone when it did finally crash onto the shore, flushed out the sandy soil around it and let it fall to the ground. Its been there ever since.

Amistad connection

Credit: Tara Conry

You may have heard the story of the Amistad or even seen Steven Spielberg's 1997 blockbuster about the uprising that took place on the Spanish ship, which was being used to transport slaves from Africa to Cuba. But did you know the ship actually dropped anchor at Montauk Point in the summer of 1839? After the slaves had killed the captain and overpowered the crew, they came ashore here, seeking food and water as their supplies dwindled. It was here that the U.S. Navy discovered the ship and the roughly 50 illegal slaves on board, and captured it. The Africans were arrested and taken to New Haven, Connecticut, where they were charged with piracy and murder, but later acquitted of all charges.