This time, Election Day could turn into Election Month

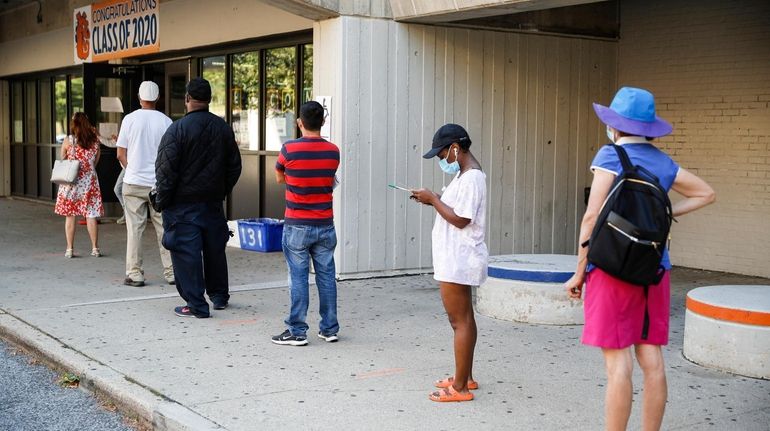

Voters wait in line to cast their ballots in New York's primary election at a polling station inside Yonkers Middle/High School on June 23 in Yonkers. Credit: AP/John Minchillo

It took nearly a month for many of New York’s congressional primary contests to officially be called final.

That’s a preview for how November might play out. Forget Election Night. Get ready for election week. Or month.

Only 25¢ for 5 months

It took nearly a month for many of New York’s congressional primary contests to officially be called final.

That’s a preview for how November might play out. Forget Election Night. Get ready for election week. Or month.

The coronavirus pandemic is triggering a major shift to mail-in, absentee paper ballots that will take time to tally. For the presidential election, it could take days or weeks to determine a winner in close states.

But even in clearly “red” or “blue” states, outcomes for down-ballot contests for Congress and state legislatures likely will be delayed too.

Americans should get ready to adjust their expectations, election experts and state officials said.

“I do think voters definitely need to be prepared to wait longer to see results than they are used to. Adjusting expectations is a huge part of this,” said Sean Morales-Doyle, deputy director of the New York University-based Brennan Center, which analyzes voting, state governments and other issues. “There’s become this tradition of getting quick results but it’s just not the way it’s going to work this year – and maybe not the way it will work in the future.”

He added: “And as long as everyone understands that, we’ll be fine.”

Since the pandemic hit, New York and many other states have tried to expand absentee balloting to accommodate voters – and poll workers – who are hesitant to go to polling sites for fear of spreading infection.

Adjusting on the fly sparked some issues -- chiefly, a shortage of poll workers and a burst of paper ballots that delayed results. Some entities such as schools that host polling sites refused to open this time. Statewide, more than 1.6 million voters had requested mail-in ballots -- more than 10 times the number of mail-in ballots cast in the 2016 presidential primary, according to the state Board of Elections. In late June, officials said about 800,000 of those ballots had been submitted.

But some voters didn’t receive their absentee ballots before Primary Day, forcing them to sit out or vote in person.

“The election system is not designed for a pandemic,” Blair Horner of the New York Public Interest Research Group said.

But the shift away from in-person voting on Election Day has been growing.

In 1992, about 92% of voters cast their ballot in person, according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. By the 2018 midterm elections, it had fallen to 62%.

The trend began slowly, with some states loosening the requirements for voting absentee. In the last 20 years, five states had switched to full vote-by-mail systems and others dropped the demand that voters supply an excuse to vote absentee. Many states – including New York – added “early voting” periods whereby someone can go to a polling site a week or more in advance to vote.

Now, with the pandemic sparking a need to avoid crowded spaces, Lee Drutman, a senior fellow at the New America think tank in Washington, has asked whether “2020 may mark a sharp turning point, where one-day in-person voting becomes a relic of the past, like landlines and cassette tapes.”

“My guess is once states begin to put these new systems in place, people tend to” want to keep them, even if the process started out as provisional, Drutman said in an interview.

The Brookings Institution recently assessed states’ vote-by-mail pandemic preparedness, giving New York a “B.” The state didn’t earn an “A” because rather than automatically mailing ballots to registered voters, New York requires voters to apply for the ballot. It could also improve access by using ballot drop-off boxes.

Elaine Kamarck, one of the authors of the Brookings study, said states have been improving the paper-ballot process but face two big issues this year: Buying more electronic scanners to read ballots and hiring more people to complete the vote count; and resisting the urge to close a lot of polling sites because some voters prefer in-person voting and find the mail-in process confusing.

She said determining a presidential winner could take a week; congressional and other down-ballot races could take longer.

The “silver lining” could be a more secure election, she said.

“Before the pandemic, our biggest worry was Russian interference. We know they tried very hard to get into state” computerized election systems, Kamarck said. “But you can’t hack a paper ballot.”

She said claims of paper ballots being susceptible to fraud are widely overblown and not successful on any noticeable scale. The most notable incident involved a North Carolina congressional race in which Republican operative was arrested and accused of improperly collecting and possibly tampering with ballots.

New York still has work to do before November, Horner said. A big improvement would be to adjust the timetable to let people obtain absentee ballots well ahead of Election Day, and maybe move up the deadline for applying.

For the primary, the application deadline was one week before the vote, which simply wasn’t enough time for some to receive the ballot, he said.

Getting enough poll workers will be another issue, Horner said. He wondered whether this issue could, in the long run, spark the state to get away from political parties running the system and switch to civil-service workers.

States are pressing Congress to supply more money – especially for equipment and workers -- to help them carry out the election during the pandemic.

“We’re in a crisis mode and it would be wonderful if we had more money from the federal government to help conduct this election,” said Assemb. Charles Lavine (D-Glen Cove), chairman of the State Assembly Elections Committee.

Lavine said he considered the June primary a “practice run” that “by and large, county election boards handled quite well” even if results have been delayed. As for November, he said legislators still are concerned about whether “mechanically, are we going to be able to do this successfully?”

The Assembly, Senate and Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo are having an “ongoing conversation” about legislation that might be necessary before November, Lavine said. Further, he believes the public is becoming aware Election Day this year will be different.

“Especially in this year, they understand the importance of the need to vote,” Lavine said, “and the need to be patient.”

Water contamination probe at MacArthur ... Indian PM coming to LI ... Takeaways from Trump rally ... Islanders, Rangers camp