Insiders worried Brookhaven landfill ash was hazardous, Covanta's internal records show

Long Island’s leading waste incinerator for years dumped ash at Brookhaven landfill that it couldn’t be certain was nonhazardous, with company employees acknowledging in internal email that they were “lucky” state regulators didn’t challenge them, a Newsday investigation found.

Engineers at Covanta Hempstead, which burns household trash for Brookhaven and six other municipalities, suspected for nearly a decade that ash practices at their Westbury facility were risky, imprecise and contrary to what they represented to the Department of Environmental Conservation, newly revealed private correspondence shows.

The corporate communications, filed recently as lawsuit exhibits, also show the DEC, the state's environmental protection agency, at times abdicated its watchdog role over a highly regulated industry with potential for air and groundwater pollution.

While the state ultimately called Covanta's ash disposal "a problem," revelations of its lax oversight have angered North Bellport, a predominantly Black and Latino community near Brookhaven landfill, and left residents to face the possibility that toxic heavy metals could have contaminated the environment.

Some of their concerns have historically stemmed from so-called “fly” ash, which may contain elevated levels of lead and cadmium. Those metals can cause certain cancers, including those of the lung and kidney, with long-term exposure, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Dry, powder-like fly ash — when not properly mixed with heavier, more-benign “bottom” ash — is more likely to become airborne and blow into dust clouds or seep into the groundwater supply, environmental experts say.

The internal records reveal that Covanta Hempstead struggled for roughly eight years to deliver ash to the landfill that matched the combined bottom and fly ash samples it used to pass required toxicity tests and be deemed nonhazardous by DEC.

New Jersey-based Covanta, which sells the energy from its local waste incineration to LIPA, denies all wrongdoing and asserts its ash has never been proved hazardous.

People who live and work near the town-run dump long have alleged the 50-year-old facility is to blame for their health problems. North Bellport has levels more than double the Suffolk County rate of adult emergency department visits for asthma, according to state Department of Health data, and more than two dozen plaintiffs have sued Brookhaven in trying to tie the landfill to their cancers and other illnesses.

But no state agency has found widespread ash pollution from the Brookhaven landfill or a link from any landfill exposure, including odors from construction and demolition debris that have been the most frequent source of community complaints, to adverse health impacts.

The DEC did not issue Covanta's Westbury plant any environmental violations at the time, but is now investigating whether it improperly disposed of hazardous ash between 2006 and 2014. The probe came after landfill critics objected to the terms of a potential settlement in a “whistleblower” lawsuit stemming from the company’s ash practices.

In numerous instances, the DEC overlooked potential problems at Covanta Hempstead, Newsday found, including a period of four months in 2007 when the facility sent Brookhaven landfill its ash despite a failed toxicity test. Its monitor assigned to the incinerator at the time omitted negative information from inspection reports, declined to issue at least one confirmed violation, and — after the state began investigating the whistleblower complaint — suggested to the company it had a mole in its ranks.

Covanta, which in 2021 reported roughly $2 billion in revenues, has four local "waste-to-energy" plants. It also was slow to make equipment upgrades in Westbury that would have made it easier to mix the ash there in an industry-standard way, documents show, despite employees' repeated concerns of matching landfill ash to test samples.

Had the DEC deemed the ash hazardous, the company would have been required to haul it off Long Island. That, according to an executive’s sworn testimony, could have doubled its landfill disposal costs, which last year were roughly $21 million. The Brookhaven landfill is barred from accepting hazardous waste, and a cleanup, if the material is ever found toxic, would cost a minimum of tens of millions of dollars, based on an analysis of other area environmental projects.

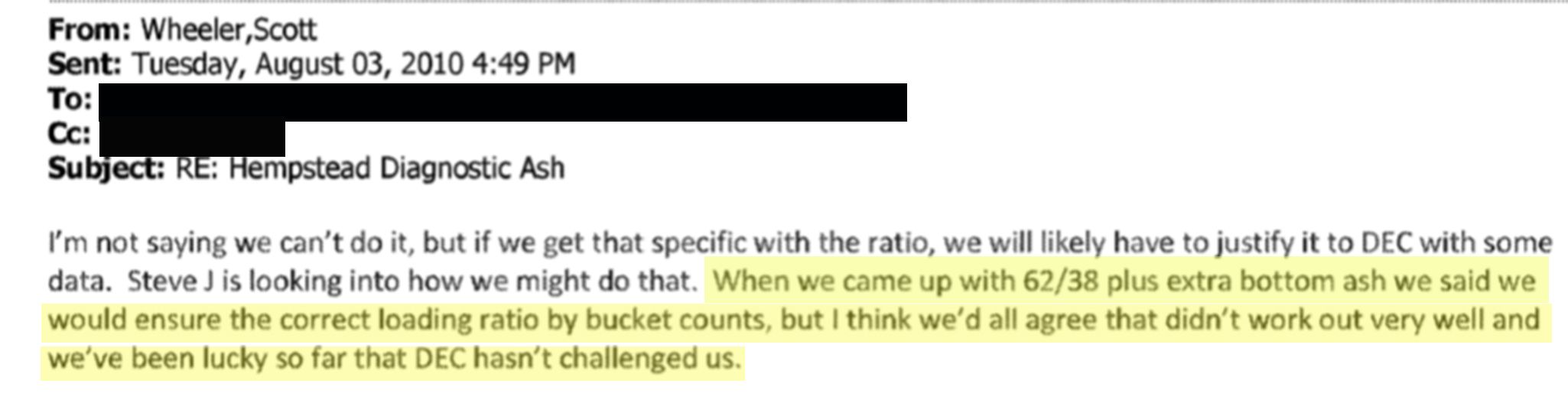

"We've been lucky so far that DEC hasn't challenged us," Scott Wheeler, a Covanta Hempstead environmental engineer, wrote to colleagues at one point, discussing company hardships of trying to get the right mix of fly and bottom ash before sending it to the landfill.

As the DEC's probe of Covanta continues, the agency in August notified Brookhaven Town it must address a newly discovered plume of harmful "forever chemicals" discovered in groundwater south of the landfill. Such chemicals, notably the likely human carcinogen PFAS, are common in the types of household products that have been incinerated and dumped at the landfill for decades — as well as construction debris separately disposed there — but regulators did not blame a specific source for the pollution.

The Brookhaven Landfill Action and Remediation Group, an activist organization led by residents who seek the closure of the landfill, said it supports the state's acknowledgment of the plume, but added, "We do not understand why it took so long for the DEC to do its job in addressing an obvious and present threat to our groundwater and our communities."

The Brookhaven Landfill Action and Remediation Group demonstrates in Bellport in April. Credit: Daniel Goodrich

Private discussions about ash

Newsday's investigation relies on records found in the ongoing whistleblower lawsuit filed against Covanta a decade ago in state court, initially under seal. They include dozens of examples of the company's private discussions about the ash it processed in Nassau and disposed of at the Brookhaven landfill's 192-acre expanse of ash and construction waste piles, some nearly as tall as the Statue of Liberty and surrounded by vegetation and wildlife.

The core issue, the lawsuit documents reveal, is that Covanta Hempstead told the DEC its outgoing ash met a specific mix of the “bottom” and “fly” components that minimized the finer and lighter fly ash containing the heavy metals captured in air pollution filters.

But during the lawsuit period the facility didn’t mix its ash like it did the samples it submitted to a laboratory roughly twice a year for the required toxicity testing.

Covanta told the DEC its test samples were “reflective of facility loading” of the ash that went to the landfill, records show. Instead, it used a large bucket crane to layer pure fly ash with bottom ash in Brookhaven-bound trailers in a way employees dubbed “the lasagna approach.”

Regulators learned of the practice in 2014 and stopped it shortly after the whistleblower, former Covanta maintenance employee Patrick Fahey, filed his first complaint. But years before, it drew suspicion from company executives and truck drivers alike, internal emails show.

The correspondence shows that Covanta environmental engineers and managers called the company's ash practices a “risk item that needs to be mitigated”; observed that some trucks had “a lot of fly ash exposed”; and worried if the DEC began testing ash directly from trucks that it could be a “disaster.”

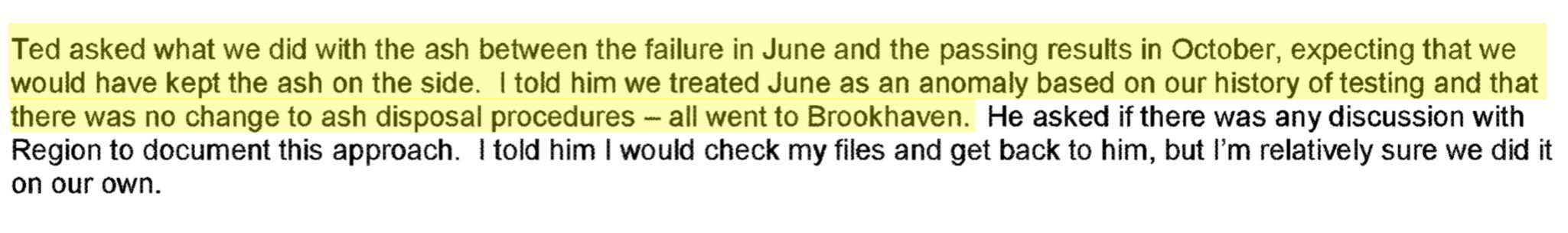

Wheeler also recounted to colleagues that the company didn’t immediately tell regulators it had delivered the four months of ash loads to Brookhaven during a period when its samples failed toxicity testing for cadmium.

Despite a DEC official "expecting that we would have kept the ash on the side," Wheeler wrote, the company told the official it treated the failure as an "anomaly" and that "there was no change to ash disposal procedures — all went to Brookhaven."

Covanta spokeswoman Nicolle Robles declined Newsday’s requests to interview company executives, but said in an emailed statement: “Covanta has produced tens of thousands of pages of documents in this case. Those records overwhelmingly demonstrate Covanta’s compliance and transparency.”

“Despite years of discovery in the decade since he initiated this action, the whistleblower has produced no evidence of any health or environmental harm,” Robles wrote.

Covanta recently hired an environmental expert who reviewed testing results from water that seeps through waste piles at the landfill and found “very low” concentrations of lead and cadmium, Robles said.

While the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the DEC have issued Brookhaven landfill violations for failing to control odors, the government does not classify the facility a significant threat to the environment. Regular air or soil testing outside the dump’s boundaries is not required, as it is with the formal government cleanup program known as "Superfund" at sites elsewhere on Long Island.

Groundwater in the area, separate from the landfill, is routinely monitored by state and local authorities.

The DEC, however, has sometimes responded to community complaints with investigations. Over the past decade, it has provided canisters to staff at a nearby school to test the air during landfill odor episodes and petri dishes to residents to collect falling ash particles that they suspected were blowing from the landfill.

The state health department’s three investigations of community cancer cases, spanning from the 1990s to 2019, all concluded that there were no links to the landfill.

'We've been let down'

In its legal filings, Covanta rebutted the significance of the internal documents, noting that they reveal no actual environmental violations. The company stated that portraying its ash practices as concerning is misleading, since the "DEC knew about — and often approved — most of the challenged practices," including later calling the approach to the failed ash test "reasonable."

The practices [Fahey] now challenges were ... conducted in plain view of the on-site DEC monitors and other DEC personnel, who never found a violation.

—Michael W. Ross, a lawyer for Covanta

“The practices [Fahey] now challenges were either affirmatively disclosed to the government regulator responsible for environmental oversight … or were conducted in plain view of the on-site DEC monitors and other DEC personnel, who never found a violation,” Michael W. Ross, a lawyer for Covanta, wrote in a legal filing last year.

In late 2021, more than two years after Fahey’s case against Covanta first became public, Gov. Kathy Hochul ordered the DEC to open what it called a "comprehensive investigation into allegations of improper ash mixing and disposal of ash by Covanta at the Town of Brookhaven landfill."

The probe began after North Bellport residents complained about proposed lawsuit settlements that wouldn’t have provided funds for potential environmental cleanups. Roughly 20,000 people live within several miles of the landfill, most of them in North Bellport, but also in Yaphank and Brookhaven hamlets.

Hannah Thomas, co-founder of the Brookhaven Landfill Remediation and Action Group, seeks the closure and cleanup of the Brookhaven Town landfill. Credit: Newsday/Steve Pfost

“We’ve been let down,” said Hannah Thomas, a 65-year-old North Bellport resident and co-founder of Brookhaven Landfill Action and Remediation Group. “There’s no one truly monitoring what’s coming in here.”

Dry fly ash, even without elevated levels of toxic metals, can cause respiratory irritation, according to environmental health experts.

“It's subject to [federal] restrictions and regulations for a reason,” said Dr. Kenneth Spaeth, division chief of occupational and environmental medicine at Northwell Health and Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine. “And so it certainly has the potential to pose hazards to those who might be exposed to it.”

Spaeth, who spoke generally, said pure fly ash could hypothetically pose dangers through inhalation, as well as through soil and groundwater, assuming it either escaped the Brookhaven landfill by blowing off waste piles or piercing landfill liners.

“I think for the residents and the communities in the immediate area, they certainly have a legitimate basis to ask questions and make sure that it’s not posing any risk,” he said, “because it has that potential for sure.”

The DEC said its protocols are meant to validate ash as nonhazardous before it leaves incinerating facilities, and that the material isn’t tested again once it’s sent out for disposal.

Fly ash in the community

In 2014, Fahey secretly recorded Edward Sandkuhl, then a senior Covanta Hempstead engineer, saying of ash at the landfill: “ … when you go out to Brookhaven, it's … everywhere."

He told Fahey he had visited the dump and saw “fly ash blowing off the [expletive] mountain,” which, at up to 270 feet tall, Sandkuhl compared to Mount Everest.

“You could taste the ash. It was in your mouth,” said Teri Palermo, of East Patchogue, who worked for more than 30 years as a special-education teacher at Frank P. Long Intermediate School in Bellport, which is less than a mile downwind from the landfill.

Palermo, 70, who retired in 2016, has survived lung and breast cancers that she blames on prolonged exposure to landfill odors and chemicals. She is one of the people suing Brookhaven Town over alleged landfill exposures, which the plaintiffs have defined to include construction debris odors carrying potentially carcinogenic chemicals, as well as ash.

You could taste the ash. It was in your mouth.

—Teri Palermo, longtime special-education teacher at Frank P. Long Intermediate School in North Bellport

Credit: Drew Singh

The town, which denies the lawsuit claims, derives nearly $60 million a year from the landfill’s acceptance of construction debris. Officials have said the facility is scheduled to stop accepting the debris at the end of next year.

Brookhaven has not said when it will stop accepting ash from Covanta, whose contract with the town runs through 2024. The town paid the company $22.8 million last year to accept its solid waste. Covanta, in turn, paid the town $21.6 to dispose of ash at the landfill, town officials said.

The DEC’s probe of Covanta includes examination of newly produced company records, Maureen Wren, an agency spokeswoman, said in a statement. She noted that the DEC “continues to strictly oversee and monitor facility operations.”

Neither she nor Hochul’s office responded when asked if the DEC’s probe would consider allegations that the agency had failed to properly regulate Covanta.

The DEC should not investigate allegations involving the agency’s own lack of oversight, said Judith Enck, who served as former Gov. Eliot Spitzer’s deputy secretary of the environment — overseeing the DEC — and was later an EPA regional administrator under President Barack Obama.

“They are not credible,” said Enck, who now leads Beyond Plastics, an environmental advocacy nonprofit. “The governor or DEC can deputize an independent person to do an investigation, and I think one is warranted here.”

'Throw it in and get it out'

Patrick Fahey, a former Covanta employee, filed a lawsuit that alleges the company mishandled the ash it sent to the Brookhaven landfill. Credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

Fahey's litigation, filed under seal in 2013 and not publicized until 2019, alleges that a desire to maximize profits drove Covanta’s ash practices, which he says resulted in Brookhaven and the other municipalities the company works for being defrauded.

The municipalities have sided with Covanta, which says it’s Fahey who is motivated by personal financial gain. The company notes he has tried to settle the case for financial damages that would be paid only to him, not to the local governments.

Fahey, 59, of Westchester County, started at Covanta in 2011. He first focused his whistleblower suit on what he said were substandard conditions at Covanta’s ash loading facility. But subsequent complaints keyed in on how ash was mixed and loaded.

"What I would witness is them not mixing the fly ash and bottom ash," Fahey said in an interview. "They were just trying to throw it in and get it out … and it was wrong."

Marco Castaldi, chairman of the chemical engineering department at the CUNY City College of New York, studies the waste-to-energy process. He said ash filtering at trash incinerators means the same volume of fly ash by weight would contain far-higher concentrations of volatile particulates than bottom ash.

“In theory, if the ash remains separate, and then fly ash is just shipped to a landfill, that would be a problem,” he told Newsday, noting that any potential risk would be reduced if it was moistened and solidified by bottom ash.

The period covered in the Covanta lawsuit coincided with increased complaints of ash blowing from the Brookhaven landfill and coating nearby cars and front lawns, according to Citizens Campaign for the Environment executive director Adrienne Esposito, who logged the complaints at the request of the DEC.

Those complaints, coupled with separate criticism of increased odors from the landfill's construction and demolition debris disposal, culminated in a 2016 private meeting among Esposito, residents and DEC officials. At the meeting, Syed Rahman, a DEC regional materials manager, told the group that the way landfill ash is mixed means it should not be escaping into the community.

"Their ash is not just fly ash," he said of what Covanta sends to Brookhaven, according to an audio recording of the meeting provided to Newsday by Esposito.

"It's called combined ash, it's mixed at a ratio … it has that moisture content in it," Rahman continued. "It doesn't dry out at the surface and start creating dust."

At this point, Fahey's lawsuit was still filed under seal and unknown to any of the community members. But Esposito, who had pressed the DEC to conduct additional testing for ash in the community, said, "We want to believe that, but … that's not necessarily the way it's actually happening."

Later in 2016, Carrie Meek Gallagher, then a DEC regional director, wrote to Esposito that the state had distributed petri dishes to residents “to collect falling particles” but that “initial analysis showed inconclusive results." Esposito criticized the effort as a poorly overseen “grammar school study” and said she never heard back from the DEC on the matter.

Cancer probes find no landfill link

The Brookhaven landfill looms in the background of this North Bellport neighborhood in August. Credit: Newsday/Steve Pfost

Local and state officials consistently have dismissed a link between the landfill and illnesses at the Frank P. Long school and in the larger community, saying that air testing during some of the hydrogen sulfide odor episodes reported over the years from construction debris did not show concerning levels of potential carcinogens.

In 2017, the state health department opened an investigation after school staff members logged what they said was an unusually high number of cancer cases. The agency concluded in late 2019 that the 31 cancer diagnoses that it confirmed over a 38-year-period “do not appear unusual” based on a comparison of the number and kinds of cases that would be expected in a similar population group.

A lengthier state health report in 2005 concluded Brookhaven landfill was “no apparent public health hazard … since the risk of long-term adverse health effects from site-related air contaminants is low.”

And in the mid-1990s, also responding to community complaints, state health officials wrote that while there were elevated uterine cancer rates in the area, “uterine cancer has no known environmental risk factors. All known risk factors for uterine cancer are related to individual characteristics or lifestyle choices.”

Proving that any pollution source directly caused someone’s illness is difficult. A 2012 paper published in the scientific journal Critical Reviews in Toxicology looked at 428 community cancer cluster investigations across the country conducted by state and federal authorities over the previous 20 years. It found that just three had been linked to environmental exposures.

Since then, a similar pattern has emerged elsewhere in the region. In 2019, the state health department concluded that there was “no information” suggesting that the Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island, which closed in 2002 and was long a source of odors and pollution, was connected to increased rates of thyroid cancer in the borough.

And though the former Grumman and U.S. Navy manufacturing site in Bethpage has for decades been a documented source of toxic soil and groundwater pollution, the only public health study, released in 2013, did not find “any unusual patterns of cancer” in a 20-block area closest to the property.

“The science behind this is not good at proving those connections. It's really hard to prove [even] that cigarettes made someone get cancer,” said Joshua Reno, a Binghamton University anthropology professor who worked at and lived near a Michigan landfill for a book about the societal impacts of waste. “If you want the public health, epidemiological approach to work for you, it's probably not going to prove it in a way that's going to make communities happy.”

Timothy Townsend, a University of Florida environmental engineering professor, said determining actual environmental or personal harm from the alleged toxic ash would require detailed records from Covanta and contemporaneous test results from the government.

“If I were living next to the landfill, it'd be legitimate to have questions about what's being disposed of," he said, noting that residents "should have a state regulatory agency that's out there keeping track of that and making sure that the operators are complying.”

‘All went to Brookhaven’

For years, the DEC missed or ignored signs of Covanta's questionable ash practices, the company’s internal documents show.

When the Hempstead facility in 2006 first received permission to test ash mixed in a lab, Wheeler, the environmental engineer, acknowledged to colleagues in an email the limitations of their equipment: “I don't think we'll ever be able to duplicate the exact measurements in the lab with the variability of our loading procedure … .”

In 2009, Gary Thein, then Covanta's corporate vice president of environmental quality, wrote in an email to a fellow New Jersey-based executive that he was "NOT a fan" of how the Hempstead facility handled its ash, saying that its bottom ash-testing results "are too close to the limit for comfort."

"Our attempts to treat ash have not been successful," he wrote. "I see this as a risk item that needs to be mitigated."

The DEC, also in 2009, questioned the facility's lab samples failing toxicity testing for the four months about two years prior. Covanta, in a 2008 letter that first disclosed the results to regulators, had said the June 2007 samples showed “abnormally high concentrations of cadmium.”

Now, a DEC official seemed surprised regulators hadn't been informed right away, Wheeler told colleagues in a September 2009 email recounting a conversation he had with the official.

The official “asked what we did with the ash between the failure in June and the passing results in October, expecting that we would have kept the ash on the side," Wheeler wrote. "I told him we treated June as an anomaly based on our history of testing and that there was no change to ash disposal procedures — all went to Brookhaven."

Covanta’s 2006 state-approved ash-management plan stated that if ash samples failed toxicity tests, the company would communicate with state regulators and take precautions.

“We would handle such waste in accordance with applicable laws,” the plan states. “At that time, with the [DEC’s] approval, we would determine whether it would be most appropriate to treat or stabilize the ash, or to dispose of it as a hazardous waste.”

Covanta lawyers said in court records the company was in compliance with the plan since they viewed the failure as an outlier and, after another round of tests, got passing results in October 2007.

They also noted that when Wheeler provided that explanation in 2009, the DEC official replied to him that the "justification appears to be reasonable."

‘DEC hasn’t challenged us’

The ash issues continued for years before Fahey made his complaint under seal, the internal records show.

Scott Wheeler, former Covanta Hempstead environmental engineer. Credit: Courtesy of attorneys for Patrick Fahey

In 2010, Wheeler wrote to colleagues that Covanta was still having problems matching its actual ash to the samples being blended in the lab for regulatory approval: “We said we would ensure the correct loading ratio by bucket counts, but I think we'd all agree that didn't work out very well and we've been lucky so far that DEC hasn't challenged us."

Wheeler in 2012 then warned staff in Westbury that a truck driver had asked him, about an ash-loaded truck bound for Brookhaven, "what the 'white stuff' [fly ash] was."

He wrote that he had tried "to be generic" in his answer and that he thought the driver "was OK with my explanation, but with all the extra fly ash we have been generating … we need to be careful with any future questions and be sure that there is always bottom ash on top of the load — I saw one last week with a lot of fly ash exposed."

The state attorney general’s office opened an investigation upon Fahey's initial, secret 2013 filing.

In February 2014, shortly after the office interviewed Covanta Hempstead’s on-site DEC monitor, Peter Hourigan, and his boss, Rahman, the two men paid a visit to Covanta Hempstead, court records show. Hourigan wrote in a report, "I've never witnessed worse ash condition here."

Hourigan later told Wheeler, according to an internal Covanta email, that the ash being submitted for toxicity testing "is not considered reflective of what is going out the door — and that's a problem."

Rahman made Covanta develop a plan to begin mixing its bottom and fly ash for testing in the actual incinerator pit, not in a lab. He ordered facility improvements, including a new bucket crane, which the company said it already was planning, for ensuring accurate ash ratios in trucks being sent to the landfill.

Covanta later updated its ash management plan filed with the state, explicitly stating for the first time that “a hydraulic crane … combines the bottom and fly ash in a mixing area of the residue bunker and mixes the ash thoroughly before loading the combined ash into trucks for shipment to the landfill.”

The company said in legal filings that the fact the DEC asked it to "adopt a new approach to creating test samples did not retroactively make the previously approved practices a violation." It further called most of the allegations about its ash practices mere "second guessing" of the DEC.

"The ash loading was done in full view of DEC’s on-site monitor, who had open access to the loading area," wrote Ross, the Covanta attorney.

He added that the company's regulator-approved method to load ash into trucks was "obviously imprecise” and that the ash management plan required Covanta “to approximate the stated ratio by loading trailers, not with a pair of tweezers, but with a gigantic crane bucket, which could not possibly achieve an 'exact ratio.' ”

‘Did not document’

A month after the fateful 2014 visit, Hourigan conducted another inspection, Wheeler wrote in an email, and "came back with some pictures of issues with our ash trailers," including one that was loaded and staged with no tarp to prevent ash from escaping.

Syed Rahman, DEC regional materials manager, in a video from April 9, 2021. Credit: Courtesy of attorneys for Patrick Fahey

"He did not document them in his inspection report, but said 'these are the kinds of things we will be looking at,' " Wheeler wrote to Covanta colleagues.

"He should [have] put [that] down in the inspection report, there's not a question about it," Rahman testified at his deposition in Fahey's lawsuit.

Hourigan also told Wheeler that a DEC police officer had pulled over a Covanta truck hauling ash and found it leaking liquid. He cited the issue as a breach of state environmental regulations, but when the company pledged to address the issue, he didn’t pursue a documented violation that could have resulted in a fine.

Asked in his deposition if Hourigan should have issued a violation in that case, Rahman replied, “He should have or could have.”

In June 2014, Wheeler and his colleagues were strategizing how to meet the DEC’s new requirements. They wondered if the agency would take surprise ash samples from landfill-bound trucks.

“This is going to be a pain,” Wheeler wrote.

“This can also be a disaster as well as a pain,” replied Larry Evans, then the plant manager.

“So if the results showed a failure of the [toxicity] test, that would be a disaster,” one of Fahey’s attorneys, David Kovel, later asked Wheeler at his deposition.

“Probably that’s what he means,” Wheeler replied.

Stairwell meeting

About the same time in 2014, Wheeler wrote a contemporaneous memo — labeled confidential — about an in-person meeting he had with Hourigan at the Hempstead facility. Hourigan told him that Covanta “is under a microscope,” according to the memo, and “I can get fired and lose my pension for saying anything."

Wheeler wrote that he and a colleague later wondered whether the DEC had tested ash at the Brookhaven landfill. Before Hourigan left, he motioned Wheeler into a stairwell, according to his memo, telling him, “Don’t say anything about what I said to anybody because you never know who you’re talking to.

“Do you understand the implications of the statement I just made?”

Hourigan since has died, but Rahman testified if Hourigan tipped off the company he was supposed to be regulating that it had a possible whistleblower, it would “absolutely” be very wrong, and “inappropriate.”

For people who live near Brookhaven landfill and represent the residents, the internal documents show failings on multiple levels.

It's a disgrace. It’s a concern to us that the monitoring is done properly, and that has not happened.

—Georgette Grier-Key, Brookhaven NAACP chapter president

Credit: Randee Daddona

“It's a disgrace,” said Brookhaven NAACP chapter president Georgette Grier-Key, after hearing some of Newsday’s findings. “It’s a concern to us that the monitoring is done properly, and that has not happened.”

North Bellport resident Monique Fitzgerald, Thomas’ niece and another co-founder of Brookhaven Landfill Action and Remediation Group, accused Covanta of “knowingly not [meeting] its legal obligation to follow the regulations” and the town of failing to adequately investigate on behalf of residents.

She added that the DEC failed by not using its power to revoke permits for Covanta or the landfill for violating environmental regulations and failed to “plan for a waste-management system that will achieve environmental justice."

“What is clear here,” Fitzgerald said, “is all of these parties are liable for what happened at Covanta and subsequently the Brookhaven landfill — and ultimately for the harms to the proximate communities.”

Newsday Live Author Series: Christie Brinkley Newsday Live and Long Island LitFest present a conversation with supermodel, actress and author Christie Brinkley. Newsday's Elisa DiStefano hosts a discussion about the American icon's life and new memoir, "Uptown Girl."

Newsday Live Author Series: Christie Brinkley Newsday Live and Long Island LitFest present a conversation with supermodel, actress and author Christie Brinkley. Newsday's Elisa DiStefano hosts a discussion about the American icon's life and new memoir, "Uptown Girl."