Brookhaven sided with landfill vendor Covanta after whistleblower raised concerns about ash, records show

The Brookhaven landfill looms in the background of this North Bellport neighborhood in August. Credit: Newsday/Steve Pfost

Town of Brookhaven leaders had a choice.

After a whistleblower alleged the waste incinerator where he worked had sent hazardous ash to the town landfill — potentially polluting air and water in surrounding communities — town officials could have joined the case and pursued damages on behalf of the community. Or they could have rejected the claims and sided with a vendor that it shared a profitable contract with.

They chose to back the vendor, a Newsday investigation found.

That vendor, Covanta Hempstead, which burns Long Island's garbage for energy, denies wrongdoing, and asserts its ash never has been proved hazardous.

But internal emails and memos, newly filed in an ongoing lawsuit, show top Brookhaven officials supported the company over whistleblower Patrick Fahey, despite evidence employees at its Westbury facility suspected for years that its ash practices were risky, imprecise and contrary to what they represented to their regulators at the state Department of Environmental Conservation.

Private correspondence further reveals that Covanta Hempstead's on-site DEC monitor left out negative information from inspection reports, declined to issue a confirmed violation and even appeared to tip off the company that it was under state investigation.

The lawsuit allegations center on how the facility, for nearly a decade, handled the two types of ash generated from its incineration process — before the material was delivered to the landfill at a clip of roughly a half-million tons a year.

The DEC approved Covanta's plan to send the landfill ash that was representative of "combined" ash samples it submitted to pass required toxicity testing. The samples were mixed in a laboratory to achieve a specific ratio of the facility's heavier, more-benign "bottom" ash and its lighter, fine-particulate "fly" ash captured in pollution control filters. Fly ash is more likely to contain higher concentrations of potentially cancer-causing heavy metals.

The ash the company dumped at the Brookhaven landfill between 2006 and 2014, however, wasn't mixed like the samples, records show. Rather, pure fly ash was layered into trucks with bottom ash in a way that sometimes worried Covanta engineers and truck drivers.

Residents who live in areas surrounding the landfill long have suspected fly ash blew from the 192-acre dump and into their neighborhoods, or seeped into the public groundwater supply. Covanta, the DEC and Brookhaven say the suspicions are unproven.

But once Fahey's ash allegations were made public, records show Brookhaven, though nominally a plaintiff in the case, regularly shared legal strategy with defendant Covanta and allowed the company to ghostwrite a letter, signed by Town Supervisor Edward P. Romaine, that requested the whistleblower lawsuit be dismissed.

When that didn't work, the town submitted an affidavit from a top landfill supervisor that called the case meritless — despite that official later admitting he hadn't read the lawsuit complaint.

Nearly a decade has passed since Covanta stopped dumping ash that wasn't mixed like its testing samples, but residents surrounding the Brookhaven landfill say they have yet to feel that town officials have taken their concerns seriously and aggressively investigated on their behalf.

Some of them say the town's response to the ash lawsuit, as detailed by Newsday, fits a larger pattern of prioritizing financial interests over those of the environment and the community.

"I am not surprised," said Abena Asare, a Brookhaven hamlet resident who helps lead the Brookhaven Landfill Action and Remediation Group, a resident advocacy organization that long has been critical of the town and the DEC. "But it is incredibly frustrating and infuriating."

The Covanta Hempstead facility in Westbury. Credit: Todd Maisel

Reached by phone, Romaine referred comment to town attorneys.

"Brookhaven's position has always been that the ash received at our facility was safe, because of DEC testing that certified it as such at both the Covanta incinerator in Hempstead and again at our landfill," Michael Cahill, the town's outside counsel on the case, said in a statement.

The landfill's former supervisor, Christopher Andrade, testified in his lawsuit deposition, however, that he did not know if the DEC ever tested the ash once it was at the landfill.

And the DEC doesn't test incinerator ash after it leaves the facility where it was generated, the agency said in a statement.

Asare, 42, and other residents, including those in nearby North Bellport, a neighborhood with mostly Black and Latino residents, cite a long history of Brookhaven Town and the DEC ignoring or misleading the community around the landfill, beginning with a 1970s state pledge that the then-new dump would one day become a park with a playground, swimming pool and even a ski slope.

Brookhaven leaders asserted more recently they would finally close the facility — one of the last municipal landfills left on Long Island — at the end of next year, but later clarified that they were referring to acceptance of construction debris. No plan to halt the ash disposal has been announced. The landfill's state permit expires in 2026.

"What about the responsibility to the community that has borne the burden of Long Island's waste for 50 years?" said Asare, a Stony Brook University professor of Africana studies. "The DEC and Brookhaven Town have been in lockstep trying to make sure that business as usual continues regardless of who it harms."

'Profitable contract'

The DEC recently designated communities near the landfill, including North Bellport, as environmentally "disadvantaged," making them eligible for significant state investments in clean and efficient-energy projects. The hamlet's population is about 71% Latino, Black or multiracial, according to the 2020 U.S. Census.

It has far higher than average state levels of hospital emergency room visits for asthma, according to state health department records.

"This is an environmental sacrifice zone," said Kerim Odekon, a primary care physician and member of the activist group whose children attend Frank P. Long Intermediate School in North Bellport, which is less than a mile from the landfill.

This is an environmental sacrifice zone.

Kerim Odekon, Brookhaven Landfill Action and Remediation Group

There are now more than two dozen plaintiffs in at least three lawsuits who allege that they or family members were exposed to toxic odors and chemicals from the landfill while living or working nearby. The plaintiffs largely worked at Frank P. Long, but early this year, the mother of a 13-year-old boy who attended the school and died last year of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma filed an intent to sue.

Brookhaven has denied the landfill is a cause of the plaintiffs' illnesses, and previous state Health Department investigations haven't established a link.

There's no doubt, however, that the town's financial health has benefited from its operation of the landfill and its ash contract with Covanta.

Brookhaven last year paid Covanta approximately $22.8 million to take more than 200,000 tons of its solid waste. Covanta, in turn, paid Brookhaven a nearly equivalent total to take more than 500,000 tons of incinerator ash from the town's waste and that of several other municipalities.

The long-standing reciprocal contract, known as "trash for ash," means the town effectively has no waste-disposal costs. This allows revenue generated from acceptance of construction and demolition debris to be a boon for the town budget — an estimated $59 million this year, for example.

As the town has touted to Wall Street ratings agencies, landfill revenues in recent years have sometimes accounted for 30% of its general fund revenues.

"It is a very efficient and profitable contract for BOTH parties," a town-appointed landfill advisory committee wrote of the Brookhaven-Covanta pact in a 2021 report.

In a statement provided by Brookhaven spokesman Jack Krieger, Christine Fetten, the town's top landfill supervisor, affirmed the town's decision to stop accepting construction and demolition debris at the facility at the end of 2024.

The Brookhaven landfill takes the majority of Long Island's solid waste ash, other than from Babylon, which runs its own "ash fill." Asked about the potential of continuing to accept Covanta's ash, Fetten said the town anticipates "a limited amount" of open landfill space after construction debris is no longer accepted, but "the town has not yet determined the use, if any, of capacity remaining as of Dec. 31, 2024."

Two streams of ash

Fahey, 59, of Westchester County, filed his lawsuit in state Supreme Court in Nassau County under seal in 2013. The case was unsealed in 2017, after the state attorney general's office declined to intervene and litigate it, and it became news in 2019.

After his lawyers obtained Covanta's internal records in lawsuit discovery, Fahey focused his primary allegation on the company's ash practices. He claims the facility, which sells the electricity produced by its incineration process to LIPA, mixed and handled ash in a way that led to hazardous material going to Brookhaven for the roughly eight-year period through 2014.

Bottom and fly ash must be combined to a state-approved ratio and pass toxicity testing before disposal as non-hazardous waste. Covanta created its combined ash samples by mixing them in the laboratory for testing, telling the DEC it was "reflective" of what it sent to the landfill, records show.

Fahey alleges what was loaded into trucks was not at all reflective of the samples, since Covanta layered the two types of ash, sometimes haphazardly.

The landfill, as a result, got disproportionate amounts of dangerous fly ash, the suit claims.

"The towns should be more open into what is really going on," Fahey said in a Newsday interview. "Maybe you want to dive into it more, rather than just trying to make this thing go away."

Maybe you want to dive into it more, rather than just trying to make this thing go away.

Patrick Fahey, whistleblower

Credit: Alejandra Villa Loarca

Covanta has assailed Fahey's motives, saying he is simply looking for a large personal payout. It argues in legal filings that its ash loading was never meant to precisely match its test samples but that DEC knew and approved of its practices regardless.

"After ten years of litigation, [Fahey] has no evidence of environmental or health harm to offer this court," a Covanta attorney wrote earlier this year.

Fahey claims the municipal agencies Covanta contracts with, including Brookhaven and Hempstead towns, Garden City village and LIPA, should be entitled to damages under New York's False Claims Act, which allows whistleblowers to sue on behalf of governments that may have been defrauded by contractors.

The governments, however, assert they were not defrauded because they received the services they paid for, potential environmental consequences notwithstanding. The lawsuit is pending requests by Hempstead and Garden City to settle the case with Covanta for $250,000, legal filings show. Fahey is arguing the municipalities don't have standing to settle.

Brookhaven did not accept a similar settlement offer, with Cahill noting in his statement to Newsday that "the Town has never, and would never, waive any liability if a harm were caused in order to protect our residents."

A town-corporation alliance

When Fahey's case was first publicized in 2019, a Brookhaven statement highlighted town officials' review of the allegations and meetings with state agencies. It noted the landfill "tests are continuously conducted on material, airborne particulate matter, gas and leachate."

What Brookhaven did not say is that it already had decided it wanted nothing to do with the whistleblower's litigation.

Further, the town supported Covanta's efforts to have the New York Attorney General's Office use its authority under the False Claims Act statute to dismiss the case.

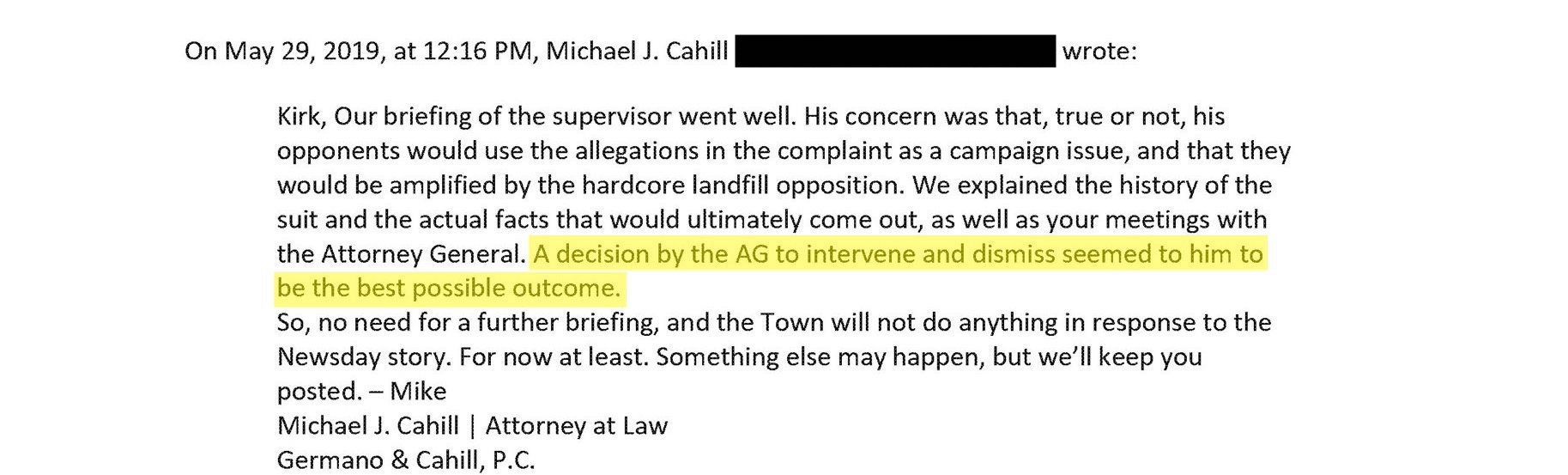

Regarding Romaine, Cahill told a Covanta attorney in a May 2019 email, "A decision by the AG [attorney general] to intervene and dismiss seemed to him to be the best possible outcome."

Town leaders initially declined to publicize its position out of political concerns, according to Cahill's internal correspondence filed in the litigation.

"His concern was that, true or not, his opponents would use the allegations in the Complaint as a campaign issue and that they would be amplified by the hard-core landfill opposition," Cahill wrote of Romaine.

Later in 2019, Cahill reported that town attorney Annette Eaderesto had suggested to him the election was still a roadblock to the town going public with its support of the company's legal position.

"We might be able to revive this in a couple of months but no way between now and November 5th," Cahill wrote to Covanta deputy general counsel Kirk Bily, referring to the 2019 general election date.

Letter of support

Brookhaven Town Supervisor Edward Romaine in Melville in September. Credit: Rick Kopstein

In October 2020, Romaine, having started a new four-year term, signed a letter requesting the state attorney general dismiss Fahey's case. A Covanta attorney had earlier sent a draft to Cahill with the message "we appreciate very much the town's consideration of this."

Written on Brookhaven letterhead, the text was nearly identical to letters signed by representatives of the other municipalities that Fahey sought to enlist as plaintiffs: the Garden City mayor and an attorney for Hempstead Town.

The letter stated Brookhaven and the others did "not believe that we were the victims of fraud … and we do not desire to continue to be parties to this litigation or to have this litigation continue in our name."

Notably, it said Brookhaven had found Fahey's allegations "to be lacking in factual and legal merit" and the town was "particularly skeptical" that Covanta failed to comply with the DEC-approved ash-management plan.

In support, the letter noted the DEC "never issued even a notice of violation ['NOV'] in connection with the practices described in the complaint."

It did not mention the internal records that suggest the same monitor told a Covanta employee he wouldn't document an uncovered ash trailer in an inspection report, declined to issue a violation regarding a leaking landfill-bound truck and — after the state began investigating Fahey's confidential complaint — told his company contact that Covanta was "under a microscope," but that he could lose his job and pension for revealing the information.

"The town is complicit," said Brookhaven NAACP chapter president Georgette Grier-Key, noting residents sometimes ask town attorneys questions about the ash case and don't receive responses. "Yet they're dealing with the opposition's attorney, giving them information? What's that called? Is it a cover-up?"

Cahill's statement on behalf of Brookhaven countered: "No decision in this case has ever been made for political reasons. However, self-described political activists have taken every opportunity to try and make this landfill a political issue."

'Not harmed'

After the state attorney general declined to dismiss Fahey's case, Covanta in 2021 secured affidavits in support of its legal arguments, including one signed by Brookhaven's then-landfill supervisor.

Andrade, at the time town commissioner of Recycling & Sustainable Materials Management, wrote, with language like the letter signed by Romaine, that the town had reviewed the lawsuit allegations "and finds them to be lacking in merit." But when attorneys for Fahey deposed Andrade later that year, he admitted under oath he never personally read the complaint.

He also said he had never visited Covanta Hempstead's ash processing facility (only a conference room) and likely wouldn't be able to identify fly ash from bottom ash.

"I would say that we were not harmed in any way," Andrade testified.

Christopher Andrade, former supervisor of the Town of Brookhaven landfill, in June 2021. Credit: Courtesy of attorneys for Patrick Fahey

Pressed by Fahey's attorneys, Andrade acknowledged that if it was proved Covanta had brought hazardous materials to Brookhaven landfill, the town could be on the hook for damages.

"If Covanta sent us hazardous material to the landfill, would that be considered serious?" Andrade said, repeating the attorney's question, before answering. "Yes."

The ash case became public amid unrelated significant landfill enforcement actions taken against the town.

In early 2019, the DEC issued notices of violation for Brookhaven failing to control landfill odors that caused "unreasonable impact and interference in the quality of life" in surrounding areas. The town spent millions to upgrade noxious gas monitoring and collection. The DEC ordered the town, in lieu of a fine, to pay for a $150,000 water-retention project in Patchogue.

In late 2020, federal prosecutors compelled Brookhaven to pay a $249,000 fine for violations of the U.S. Clean Air Act for a "failure to properly monitor and control noxious landfill gas emissions."

Adrienne Esposito, executive director of the Farmingdale-based Citizens Campaign for the Environment, said the two regulatory actions only came because of years of resident pressure amid state and town officials, under numerous administrations, denying that community odors had anything to do with the landfill.

"We understand managing a landfill is difficult and challenging," Esposito said. "However, it's done successfully in other places."

Covanta questions town's response

As an example of what they call Brookhaven's lack of transparency, anti-landfill activists cite the town's now-scuttled attempt to build a dedicated "ashfill" on town property adjacent to the existing landfill.

Plans for the project, which would have allowed the town to continue doing business with Covanta after the current landfill reaches capacity, were not made public until 2020.

But in 2019, as several Brookhaven officials pledged impending landfill closure, the town already had told Wall Street ratings agencies about the ashfill plan, records show, saying the project would help recoup revenue lost when construction debris dumping fees ceased.

The group did not learn about this until later, when it found a report that one of the ratings agencies, Moody's, had issued about Brookhaven's financial health.

"There's no communication," said Dennis Nix, a North Bellport resident who worked at the landfill as a town laborer, and has his own lawsuit against Brookhaven alleging toxic landfill chemicals made him sick in 2015. "I wish that our local government would care about what's going on in this community."

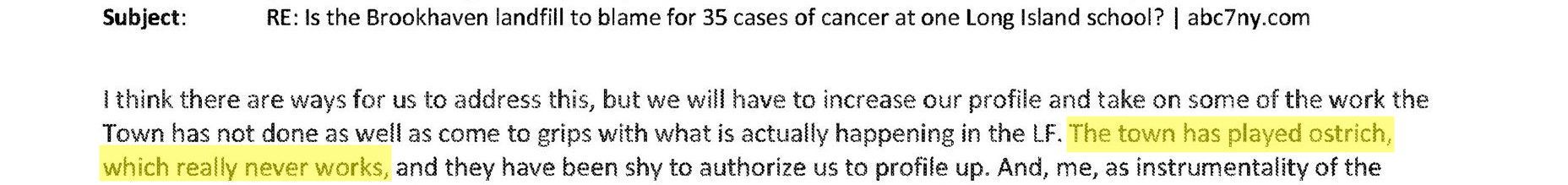

But it is not only residents who feel that Brookhaven has not fully addressed landfill concerns. An exhibit in Fahey's lawsuit reveals Covanta itself also privately questioned the town's willingness to investigate the facility.

In February 2018, before the whistleblower allegations had been made public, several company executives traded emails on a thread that began with a link to a local news report about the Frank P. Long allegations, "Is the Brookhaven landfill to blame for 35 cases of cancer at one Long Island school?"

"Not good," wrote the company's senior director for ash processing, Anthony Dell'Anno, highlighting a quote from Esposito that accused the DEC of "not looking for the problem."

"I am very concerned that this story will get bigger," replied Derek Veenhof, a Covanta executive vice president, noting an article photo showed a protester holding an "ASH" sign.

The company admitted no wrongdoing, but the executives appeared concerned with being able to freely conduct damage control.

Finally, Covanta's environmental vice president said the company couldn't count on Brookhaven to help its cause.

"I think there are ways for us to address this, but we will have to increase our profile and take on some of the work the Town has not done," wrote John Waffenschmidt, "as well as come to grips with what is actually happening in the [landfill].

"The town has played ostrich, which really never works ... ."

This is a modal window.

Picture-perfect adoptable pets ... Go fly a kite in Babylon ... Knicks Game 4 reaction ... Get the latest news and more great videos at NewsdayTV

This is a modal window.

Picture-perfect adoptable pets ... Go fly a kite in Babylon ... Knicks Game 4 reaction ... Get the latest news and more great videos at NewsdayTV

Most Popular