Only 6% of eligible Long Island school cafeterias inspected twice a year as required by federal law, among fewest in New York

Long Island’s two county health departments conducted required twice-a-year food safety inspections at only 6% of schools that receive federal money as part of the free or reduced lunch program, a Newsday analysis of state records found.

By comparison, New York's average for twice-a-year inspections in school cafeterias that participate in the National School Lunch Program was 54%, state education data from the 2022-23 school year shows.

Overall, Nassau ranked 56 and Suffolk 57 out of the state’s 62 counties for food-safety inspections — on an island that has more than 109 public school districts and three charter schools participating in the lunch program.

“To me, that’s insane,” said Rich Pandolfo, whose child goes to the Middle Country Central School District. “I would hope that they would be inspecting more than once a year.”

Maria Gartner, 41, whose children also attend classes in Middle Country, echoed the concern.

“I think that it’s upsetting that they are only checking it — maybe — twice a year, and not even all the schools would be getting that,” she said. “It’s just a 6% chance.”

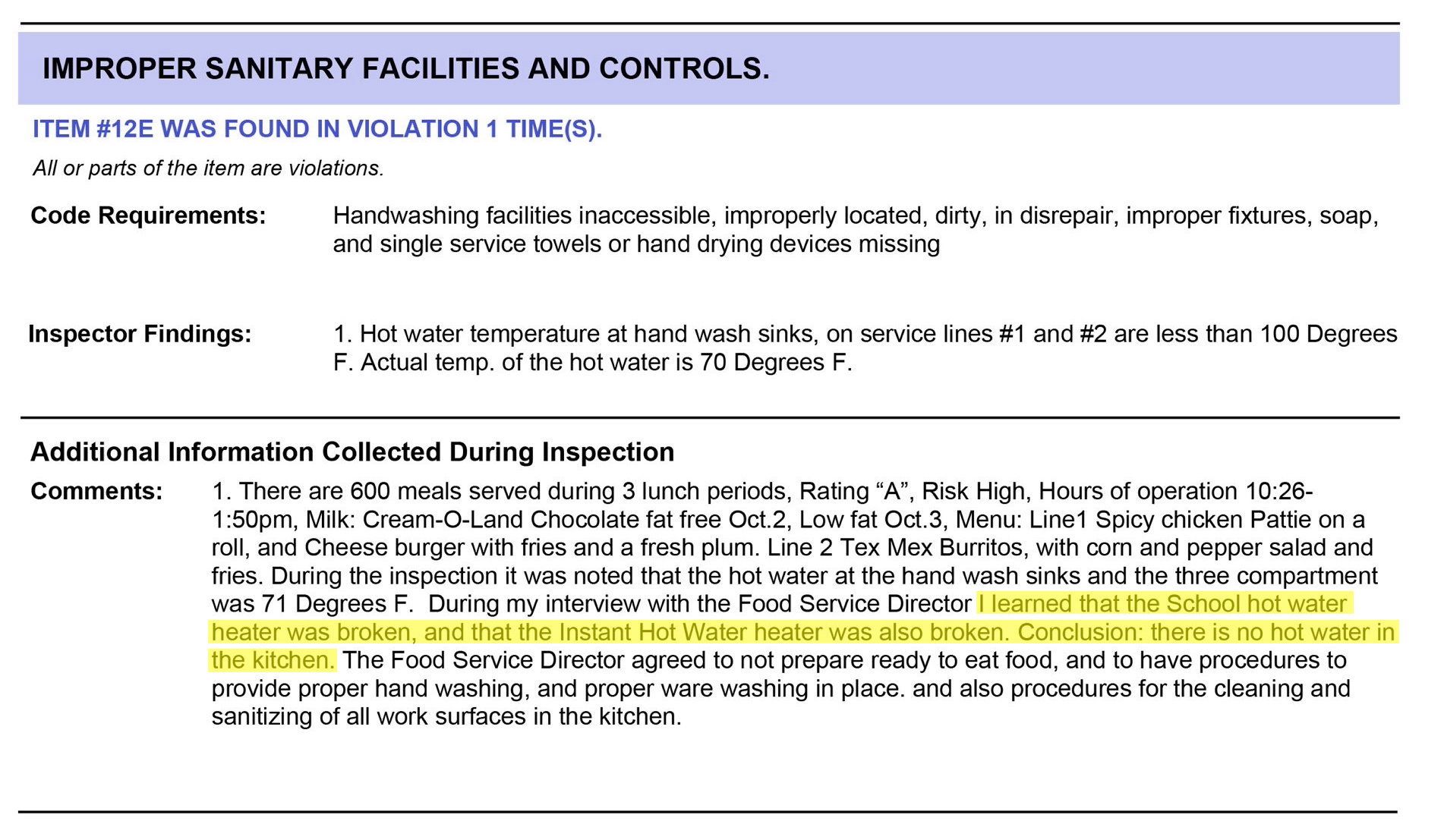

The most common violations found in cafeterias across Long Island were inadequate hand-washing facilities or toilets that were improperly located, dirty or in disrepair, Newsday's analysis of inspection reports shows. Other common problems include lack of hot and cold running water or issues with plumbing and sinks.

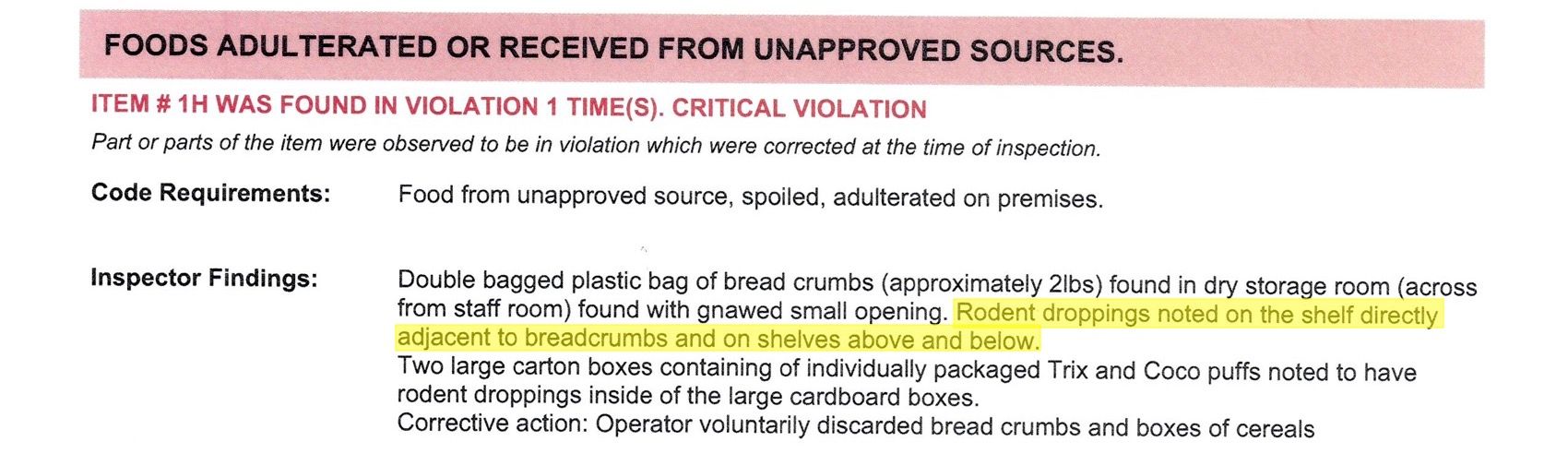

Scattered throughout the inspection reports are instances of rodent droppings, dead mice, both live and dead cockroaches and insufficient refrigeration for food storage.

Critical violations pose a threat to food safety, possibly resulting in foodborne illness, according to state and county health codes. Examples include violations regarding food temperatures, bare-hand contact with ready-to-eat foods and unapproved food sources.

Noncritical violations are commonly referred to as sanitation or maintenance violations. They typically involve general cleaning and maintenance of food service equipment or structural deficiencies. Violations for insects or rodents are not considered critical under current state and county laws.

Guidelines created in 2004 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which administers the National School Lunch Program, made states responsible for keeping track of school inspections. A 2009 change to federal regulations increased from one to two the number of required cafeteria inspections each school year.

New York State relies on county health departments for food-safety inspections. Local municipalities argue there is no need for two food-safety inspections each school year.

On Long Island, health officials inspected 49% of schools participating in the lunch program once last school year, Newsday's analysis shows. The remaining schools weren't inspected at all. Juvenile detention centers and special education schools also received federal funding, but weren't included in the analysis.

William Urbina, 34, the parent of a child in the East Meadow School District, said he'd like to see far more cafeteria inspections.

“That’s concerning,” Urbina said of Newsday's data analysis. “I really think that Long Island needs to make sure that the schools are up to par, especially for our kids.”

Rada Tarnovsky, president of Letter Grade Consulting in Brooklyn, which advises schools, hotels and restaurants on how to pass New York City health inspections, said the findings should be a “very big red flag” for Long Island parents.

“I would be very concerned if I was a parent on Long Island and my kids were eating in cafeterias that haven’t been inspected,” Tarnovsky said.

In New York City, health officials inspect on average 59% of school cafeterias twice per school year, state Department of Education data shows.

“The NYC Health Department takes seriously the responsibility to inspect school cafeterias twice annually,” said department spokeswoman Shari Logan, who added that the state Health Department has not finished reporting inspection data for fiscal 2023.

Besides twice-a-year inspections, federal rules require schools participating in the lunch program to post the most recent inspection report in a visible location and to provide a copy of the report to the public upon request, according to the USDA.

The requirement of two inspections per school year is “clearly” the law, said Bob Hibbert, a Washington, D.C., attorney with three decades of experience advising clients on food safety regulations.

But, “It is unclear how actively it is being enforced,” Hibbert said.

“The federal government just doesn't have the muscle — the financial, personnel, political muscle to compel compliance,” said Craig Green, a Temple University law professor. “That means that whatever risks would be avoided due to inspections, are real, and happening every day… And if and when that happens, then all of these records of nonenforcement will look very regrettable and problematic.”

Regan Kiembock, children nutrition director at Southampton Union Free School District and a member of the Long Island School Nutrition Directors Association, said county health officials told her “unless there is a critical violation on the first visit, they will not follow up with a second inspection as they do not have staffing to do so.”

Health department officials in both counties did not respond to questions about whether they have sufficient staff to conduct inspections.

In Suffolk, the districts with the most cafeteria violations were Sachem and Brentwood, each recording 225 citations, followed by Middle Country with 200, inspection reports from 2017 to 2023 show.

At cafeterias in the districts, inspectors found Buffalo chicken strips stored at unsafe temperatures, mouse droppings and dead mice on the floor of a storage room, unrefrigerated salad and roaches crawling on a service line, according to reports.

“Although mostly noncritical, we take all citations very seriously as we are dedicated to providing and operating in an efficient food services establishment that is clean and safe,” Sachem Superintendent Christopher Pellettieri said in a statement.

Brentwood interim Superintendent Wanda Ortiz-Rivera said most violations are resolved while the inspector is still on-site.

“There are various levels of violation severity,” Ortiz-Rivera said. “They can include a dented can of food, a lid open on the outside dumpster to conditions requiring equipment repair.”

Middle Country Superintendent Roberta Gerold contends the violations were “structural in nature and did not compromise the quality of the food services, or food, provided by the district to our students. Each finding was immediately addressed and brought up to code.”

In Nassau, the Hempstead district received a total 142 health violations from 2017 to 2023, the most of any district in the county. A school building's hot water heater was broken during an inspection on Sept. 22, 2022.

Hempstead board president LaMont Johnson said the district’s cafeterias are clean and well-managed.

“And I’m confident that the necessary repairs have been made to make sure that the water temperature is exactly what it needs to be,” Johnson said in an interview last summer, adding that he conducted his own personal inspection.

The Valley Stream Central High School District ranked second with 137 violations. In October, an inspector found “rodent droppings noted on the shelf directly adjacent to breadcrumbs and on shelves above and below.”

“The safety and health of our students is always our first priority. We are constantly working with our food service providers to maintain clean and healthy cafeteria and kitchen facilities,” Superintendent Wayne Loper said in a statement. “We take these health infractions seriously, and we will continue to strive to resolve any maintenance issues before they arise.”

The East Meadow district ranked third with 112 violations, records show. Inspectors cited schools for the presence of rodents or insects, food not protected during storage and meals not properly refrigerated.

In a statement, East Meadow Superintendent Kenneth Rosner said many of the violations were for improper water temperature settings at hand-washing sinks and improper use of a door stop.

“Regardless, upon notification of these noncritical violations, the district immediately addressed them,” Rosner said.

State Health Department regulations recommend that high-risk establishments, including school kitchens that prepare food, be inspected biannually; medium-risk establishments, including schools that receive prepared meals for distribution to students, be inspected once per year; and low-risk facilities, which generally do not serve hot or prepared meals, be inspected once every two years.

Most of the schools on Long Island are either high or medium risk, requiring more frequent inspections under state guidelines.

Suffolk County Health Department spokeswoman Grace Kelly-McGovern said in an email that there is no need to inspect high-risk cafeterias twice per year — despite state Health Department guidelines to the contrary — because of Suffolk County's “multipronged strategy, which includes a combination of inspections, food worker education, prompt complaint investigations and enforcement action.”

“We will ensure food safety and adequately protect the public health when all high-risk food service establishments are inspected once a year, when high-risk food service establishments with a history of noncompliance are inspected twice a year and when medium-risk establishments are inspected once a year,” McGovern said.

Nassau health officials also did not see the need for two food-safety inspections each school year.

“We strive to inspect most food service establishments, including school cafeterias, at least once a year and allocate our resources to conduct more frequent inspections when deemed necessary to address critical public health concerns,” said Alyssa Zohrabian, spokeswoman for the Nassau County Health Department.

Zohrabian added there is “no direct regulatory requirement” for local health departments to inspect schools that participate in the lunch program twice a school year.

But Norman Silber, who teaches consumer law at Hofstra Law School, said local health departments are skirting their responsibilities.

“The idea that local health agencies are not 'directly' required is an evasion,” Silber said. “The federal/state cooperative scheme assigns them a role, and they are required to fulfill their role.”

Silber explained that if there is a foodborne illness because of poor sanitation, it would be the fault of the county health agencies that neglected to inspect school cafeterias regularly.

Responsibility for requesting two food-safety inspections falls on school administrators, but the burden for ensuring the requests are made rests with the state, according to Education Department spokesperson J.P. O’Hare.

The state Education Department cites schools for failing to request school cafeteria inspections and can withhold money from schools that operate the lunch program. But the department has no record of ever withholding money because a Long Island district failed to request a food-safety inspection or “take corrective action,” O'Hare said.

In theory, the money schools are getting from the USDA also could cover equipment updates, but it's barely enough for the food itself, said Joshua Poveda, food service director at Evergreen Charter School in Hempstead.

“I've been here for 12 years and never been able to stay in budget,” Poveda said.

Janet Sklar, a former food service director in the Comsewogue and Bay Shore districts, said cafeterias on Long Island have old equipment, plumbing and electrical systems while money for repairs is scarce.

“When school districts float a bond to their residents for upgrades, it seldom includes funding for school kitchens and cafeterias,” Sklar said.

Marina Marcou-O’Malley, co-executive director of Alliance for Quality Education, an Albany-based public education advocacy group, said some public schools do not have the financial resources to make the type of capital improvements to a cafeteria that might be needed to avoid serious inspection violations.

These districts, she said, either do not have the reserves on hand to immediately replace a hot water heater or busted sink or are unwilling to place the burden on an already struggling tax base, who would have to vote to approve most large, long-term capital expenditure projects.

“Voters already perceive that they can’t be doing any more,” Marcou-O’Malley said. “So districts are reluctant to go through this whole process unless it's something desperately needed.”

Long Island’s two county health departments conducted required twice-a-year food safety inspections at only 6% of schools that receive federal money as part of the free or reduced lunch program, a Newsday analysis of state records found.

By comparison, New York's average for twice-a-year inspections in school cafeterias that participate in the National School Lunch Program was 54%, state education data from the 2022-23 school year shows.

Overall, Nassau ranked 56 and Suffolk 57 out of the state’s 62 counties for food-safety inspections — on an island that has more than 109 public school districts and three charter schools participating in the lunch program.

“To me, that’s insane,” said Rich Pandolfo, whose child goes to the Middle Country Central School District. “I would hope that they would be inspecting more than once a year.”

WHAT TO KNOW

- Long Island’s two county health departments conducted required twice-a-year food safety inspections at only 6% of eligible schools in 2022-23 school year, a Newsday analysis of state records found.

- Schools that receive federal money as part of the National School Lunch program must obtain two inspections per year, and the state relies on local health departments for food-safety inspections.

Among the violations found in cafeterias across Long Island were inadequate hand-washing facilities, rodent droppings, dead mice, both live and dead cockroaches and insufficient refrigeration for food storage.

Maria Gartner, 41, whose children also attend classes in Middle Country, echoed the concern.

“I think that it’s upsetting that they are only checking it — maybe — twice a year, and not even all the schools would be getting that,” she said. “It’s just a 6% chance.”

'Very concerned'

The most common violations found in cafeterias across Long Island were inadequate hand-washing facilities or toilets that were improperly located, dirty or in disrepair, Newsday's analysis of inspection reports shows. Other common problems include lack of hot and cold running water or issues with plumbing and sinks.

Scattered throughout the inspection reports are instances of rodent droppings, dead mice, both live and dead cockroaches and insufficient refrigeration for food storage.

Critical violations pose a threat to food safety, possibly resulting in foodborne illness, according to state and county health codes. Examples include violations regarding food temperatures, bare-hand contact with ready-to-eat foods and unapproved food sources.

Noncritical violations are commonly referred to as sanitation or maintenance violations. They typically involve general cleaning and maintenance of food service equipment or structural deficiencies. Violations for insects or rodents are not considered critical under current state and county laws.

Guidelines created in 2004 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which administers the National School Lunch Program, made states responsible for keeping track of school inspections. A 2009 change to federal regulations increased from one to two the number of required cafeteria inspections each school year.

New York State relies on county health departments for food-safety inspections. Local municipalities argue there is no need for two food-safety inspections each school year.

On Long Island, health officials inspected 49% of schools participating in the lunch program once last school year, Newsday's analysis shows. The remaining schools weren't inspected at all. Juvenile detention centers and special education schools also received federal funding, but weren't included in the analysis.

William Urbina, 34, the parent of a child in the East Meadow School District, said he'd like to see far more cafeteria inspections.

“That’s concerning,” Urbina said of Newsday's data analysis. “I really think that Long Island needs to make sure that the schools are up to par, especially for our kids.”

Rada Tarnovsky, president of Letter Grade Consulting in Brooklyn, which advises schools, hotels and restaurants on how to pass New York City health inspections, said the findings should be a “very big red flag” for Long Island parents.

“I would be very concerned if I was a parent on Long Island and my kids were eating in cafeterias that haven’t been inspected,” Tarnovsky said.

In New York City, health officials inspect on average 59% of school cafeterias twice per school year, state Department of Education data shows.

“The NYC Health Department takes seriously the responsibility to inspect school cafeterias twice annually,” said department spokeswoman Shari Logan, who added that the state Health Department has not finished reporting inspection data for fiscal 2023.

Besides twice-a-year inspections, federal rules require schools participating in the lunch program to post the most recent inspection report in a visible location and to provide a copy of the report to the public upon request, according to the USDA.

The requirement of two inspections per school year is “clearly” the law, said Bob Hibbert, a Washington, D.C., attorney with three decades of experience advising clients on food safety regulations.

But, “It is unclear how actively it is being enforced,” Hibbert said.

“The federal government just doesn't have the muscle — the financial, personnel, political muscle to compel compliance,” said Craig Green, a Temple University law professor. “That means that whatever risks would be avoided due to inspections, are real, and happening every day… And if and when that happens, then all of these records of nonenforcement will look very regrettable and problematic.”

Regan Kiembock, children nutrition director at Southampton Union Free School District and a member of the Long Island School Nutrition Directors Association, said county health officials told her “unless there is a critical violation on the first visit, they will not follow up with a second inspection as they do not have staffing to do so.”

Health department officials in both counties did not respond to questions about whether they have sufficient staff to conduct inspections.

Regan Kiembock, director of food services for the Southampton school district, in the lunchroom at Southampton High School in 2022. Credit: Randee Daddona

Mouse droppings, no hot water

In Suffolk, the districts with the most cafeteria violations were Sachem and Brentwood, each recording 225 citations, followed by Middle Country with 200, inspection reports from 2017 to 2023 show.

At cafeterias in the districts, inspectors found Buffalo chicken strips stored at unsafe temperatures, mouse droppings and dead mice on the floor of a storage room, unrefrigerated salad and roaches crawling on a service line, according to reports.

“Although mostly noncritical, we take all citations very seriously as we are dedicated to providing and operating in an efficient food services establishment that is clean and safe,” Sachem Superintendent Christopher Pellettieri said in a statement.

Brentwood interim Superintendent Wanda Ortiz-Rivera said most violations are resolved while the inspector is still on-site.

“There are various levels of violation severity,” Ortiz-Rivera said. “They can include a dented can of food, a lid open on the outside dumpster to conditions requiring equipment repair.”

Middle Country Superintendent Roberta Gerold contends the violations were “structural in nature and did not compromise the quality of the food services, or food, provided by the district to our students. Each finding was immediately addressed and brought up to code.”

In Nassau, the Hempstead district received a total 142 health violations from 2017 to 2023, the most of any district in the county. A school building's hot water heater was broken during an inspection on Sept. 22, 2022.

Hempstead board president LaMont Johnson said the district’s cafeterias are clean and well-managed.

“And I’m confident that the necessary repairs have been made to make sure that the water temperature is exactly what it needs to be,” Johnson said in an interview last summer, adding that he conducted his own personal inspection.

The Valley Stream Central High School District ranked second with 137 violations. In October, an inspector found “rodent droppings noted on the shelf directly adjacent to breadcrumbs and on shelves above and below.”

“The safety and health of our students is always our first priority. We are constantly working with our food service providers to maintain clean and healthy cafeteria and kitchen facilities,” Superintendent Wayne Loper said in a statement. “We take these health infractions seriously, and we will continue to strive to resolve any maintenance issues before they arise.”

The East Meadow district ranked third with 112 violations, records show. Inspectors cited schools for the presence of rodents or insects, food not protected during storage and meals not properly refrigerated.

In a statement, East Meadow Superintendent Kenneth Rosner said many of the violations were for improper water temperature settings at hand-washing sinks and improper use of a door stop.

“Regardless, upon notification of these noncritical violations, the district immediately addressed them,” Rosner said.

Noncritical violations

State Health Department regulations recommend that high-risk establishments, including school kitchens that prepare food, be inspected biannually; medium-risk establishments, including schools that receive prepared meals for distribution to students, be inspected once per year; and low-risk facilities, which generally do not serve hot or prepared meals, be inspected once every two years.

Most of the schools on Long Island are either high or medium risk, requiring more frequent inspections under state guidelines.

Suffolk County Health Department spokeswoman Grace Kelly-McGovern said in an email that there is no need to inspect high-risk cafeterias twice per year — despite state Health Department guidelines to the contrary — because of Suffolk County's “multipronged strategy, which includes a combination of inspections, food worker education, prompt complaint investigations and enforcement action.”

“We will ensure food safety and adequately protect the public health when all high-risk food service establishments are inspected once a year, when high-risk food service establishments with a history of noncompliance are inspected twice a year and when medium-risk establishments are inspected once a year,” McGovern said.

Nassau health officials also did not see the need for two food-safety inspections each school year.

“We strive to inspect most food service establishments, including school cafeterias, at least once a year and allocate our resources to conduct more frequent inspections when deemed necessary to address critical public health concerns,” said Alyssa Zohrabian, spokeswoman for the Nassau County Health Department.

Zohrabian added there is “no direct regulatory requirement” for local health departments to inspect schools that participate in the lunch program twice a school year.

But Norman Silber, who teaches consumer law at Hofstra Law School, said local health departments are skirting their responsibilities.

Norman I. Silber, Hofstra Law School professor. Credit: Yale Law School/Peter Otis

“The idea that local health agencies are not 'directly' required is an evasion,” Silber said. “The federal/state cooperative scheme assigns them a role, and they are required to fulfill their role.”

Silber explained that if there is a foodborne illness because of poor sanitation, it would be the fault of the county health agencies that neglected to inspect school cafeterias regularly.

Funding never enough

Responsibility for requesting two food-safety inspections falls on school administrators, but the burden for ensuring the requests are made rests with the state, according to Education Department spokesperson J.P. O’Hare.

The state Education Department cites schools for failing to request school cafeteria inspections and can withhold money from schools that operate the lunch program. But the department has no record of ever withholding money because a Long Island district failed to request a food-safety inspection or “take corrective action,” O'Hare said.

In theory, the money schools are getting from the USDA also could cover equipment updates, but it's barely enough for the food itself, said Joshua Poveda, food service director at Evergreen Charter School in Hempstead.

“I've been here for 12 years and never been able to stay in budget,” Poveda said.

Janet Sklar, a former food service director in the Comsewogue and Bay Shore districts, said cafeterias on Long Island have old equipment, plumbing and electrical systems while money for repairs is scarce.

“When school districts float a bond to their residents for upgrades, it seldom includes funding for school kitchens and cafeterias,” Sklar said.

Marina Marcou-O’Malley, co-executive director of Alliance for Quality Education, an Albany-based public education advocacy group, said some public schools do not have the financial resources to make the type of capital improvements to a cafeteria that might be needed to avoid serious inspection violations.

These districts, she said, either do not have the reserves on hand to immediately replace a hot water heater or busted sink or are unwilling to place the burden on an already struggling tax base, who would have to vote to approve most large, long-term capital expenditure projects.

“Voters already perceive that they can’t be doing any more,” Marcou-O’Malley said. “So districts are reluctant to go through this whole process unless it's something desperately needed.”

School lunches

- Congress passed final rule in 2009 that increased the number of mandatory food safety inspections for schools from once a year to twice a year.

- State education agencies must collect the number of school cafeteria inspections and submit it to the Food and Nutrition Service, a division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- The National School Lunch Program was established under the National School Lunch Act, signed by President Harry Truman in 1946.

'It's disappointing and it's unfortunate' Suffolk Police Officer David Mascarella is back on the job after causing a 2020 crash that severely injured Riordan Cavooris, then 2. NewsdayTV's Andrew Ehinger and Newsday investigative reporter Paul LaRocco have the story.

'It's disappointing and it's unfortunate' Suffolk Police Officer David Mascarella is back on the job after causing a 2020 crash that severely injured Riordan Cavooris, then 2. NewsdayTV's Andrew Ehinger and Newsday investigative reporter Paul LaRocco have the story.