Bay Shore schools kept teacher Thomas Bernagozzi despite sexual abuse allegations spanning 30 years, investigation shows

This is a modal window.

Robby Hubbard said he had buried his memories of third grade teacher Thomas Bernagozzi repeatedly sexually abusing him behind an obscured classroom window in 1973, never speaking of it to anyone.

But when he returned to the Bay Shore school district as a nighttime security guard more than a decade later, in the mid-1980s, and saw Bernagozzi at a meet-the-teacher night, he was overcome by rage. Stomping around, he waved his arms and loudly called Bernagozzi a “child molester.” He stopped only when a custodian physically ushered him away from parents and teachers.

“I just wanted to freaking kill him,” Hubbard, now 59, told Newsday in January in a conference room in Jacksonville, Florida, near his home in St. Augustine.

For months, Hubbard relentlessly pressed the district to investigate Bernagozzi, by then an award-winning teacher who was popular among students, parents and administrators.

Finally, the district told Hubbard to drop the issue. When he refused, he said they fired him from his part-time job “to get me to go away.”

Today, Suffolk prosecutors refer to Bernagozzi, 75, as “a serial child abuser” accused of sexually abusing scores of male students between the ages of 4 and 12 during a 30-year teaching career that ended in 2000.

“Unfortunately, the statute of limitations bars direct prosecution on most of the horrific conduct that has been inflicted upon many of the victims who have come forward,” Suffolk Assistant District Attorney Dana Castaldo said.

He pleaded not guilty in Suffolk Supreme Court in January to charges of sodomy and sexual conduct against a child involving two former students. He faces up to 25 years in prison on each charge. The single count of sodomy relates to a student who was 4 years old when Bernagozzi allegedly abused him from September 1989 to January 1990, court records state. The sexual conduct against a child charge involved a different student who was between 8 and 10 years old when Bernagozzi allegedly abused him from November 1997 to January 2000, the records show.

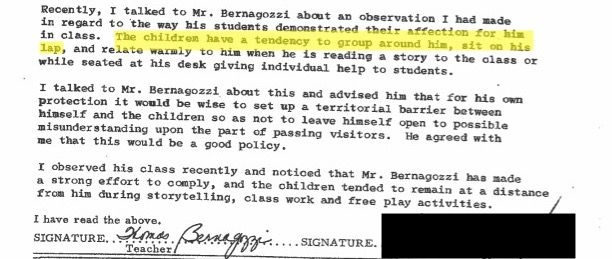

A Newsday investigation — following interviews with seven men who allege Bernagozzi abused them as youngsters, three administrators who oversaw Bernagozzi, and a review of thousands of pages of court and school documents — found that the district knew of at least five alleged incidents in 30 years of teaching, and documented red-flag behaviors such as having children on his lap in class. But the district never moved to terminate Bernagozzi, and Suffolk police said they have no record of being contacted.

Among Newsday's findings:

The district investigated an allegation of “pedophilia” in 1971, a year into Bernagozzi’s teaching career, and placed the documentation in a sealed envelope in his personnel file, By 1994, that envelope was missing from the file, according to a district memo Newsday obtained, District officials testified in depositions related to civil lawsuits against the district that they were told the allegations were determined in 1971 to be "unfounded," , Two decades later, in 1992, Bay Shore suspended Bernagozzi while investigating an allegation he sexually abused a boy after school in a bathroom, A district memo Newsday obtained from court records said the boy’s parents dropped the allegations “at the suggestion of” then-Superintendent Crescent Bellamore because he said “the child would be subject to needless trauma,” Bellamore died in 2015, No records from that investigation exist, the district said, Parents of two boys reported separate abuse allegations to administrators at Bernagozzi’s elementary school in 1977 and 1987, according to court records and interviews, There is no evidence from the court file that the district investigated or took any action either time, , Bernagozzi’s everyday interactions with boys raised concern among administrators, Principals told him to stop having kids sit on his lap in class as early as 1975 and again in 1994, Meanwhile, Bernagozzi regularly stayed after school with boys to play sports, often without shirts, took their pictures and regularly drove them home, according to court documents and interviews, He took boys on trips to the beach, ice skating, to a local fitness center, New York City and strawberry picking, School officials allowed these because they believed he had parental permission, records show, Bernagozzi retired in June 2000, then returned to Gardiner Manor Elementary the following school year as a substitute teacher and volunteer, However, a staffer’s memo in November 2000 detailed how he had taken a boy into a bathroom the previous March, when he still taught third grade, Then-Superintendent Evelyn Holman banned him from school property and ordered him to not contact students or their families, according to court documents, .

Suffolk police arrested Bernagozzi at his Babylon home in December. He is free on a $600,000 bond and is due back in court March 19.

The allegations against Bernagozzi surfaced in 45 separate lawsuits filed against the Bay Shore school district between July 2020 and August 2021 under the Child Victims Act. State legislators in 2019 passed the act, which allowed childhood survivors of sexual abuse a one-year window to file a lawsuit for damages. Then-Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo extended the window a year, to August 2021, because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before the law's passage, survivors were prevented from filing suit once they turned 23.

The 45 suits, including one filed by Hubbard, are the most against any of Long Island’s 124 public school districts, according to Newsday's review of court records. Bernagozzi is central in all the suits.

Newsday does not identify victims of sexual abuse without their consent. Hubbard and three other men who filed lawsuits agreed to use their names in this story.

Bernagozzi “used his position of power, authority and trust over his victims and their families to gain access and [create] opportunities for the children to carry out these heinous acts,” Castaldo said.

The allegations in the lawsuits occurred in nearly every year Bernagozzi taught at Bay Shore’s Gardiner Manor and Mary G. Clarkson elementary schools. The district filed countersuits against Bernagozzi, arguing he should be held responsible instead of the school system.

Bay Shore Superintendent Steven Maloney and board president Jennifer Brownyard said in a joint statement that they are “constrained and unable to comment … due to pending and ongoing litigation.”

Bernagozzi did not return messages seeking comment for this story. He said in December that his Huntington-based attorney, Samuel DiMeglio, advised him not to speak to reporters. Asked for comment for this story, DiMeglio said, "We are not responding." DiMeglio said in Suffolk Supreme Court on Jan. 30 that Bernagozzi "vehemently denies the allegations."

The first trial in the civil lawsuits against the Bay Shore district begins April 2 in Suffolk Supreme Court.

The court records do not state how much money the plaintiffs are seeking from the district.

A Newsday investigation found dozens of school districts have paid millions to settle Child Victims Act lawsuits by former students who say teachers, administrators and fellow students sexually abused them. Including the claims against Bay Shore, 150 more lawsuits are ongoing.

A total of 27 school districts have settled 42 lawsuits for a combined $31.6 million, a Newsday analysis of court records shows.

In the summer of 1994, the Bay Shore district hired Claire Lenz from the Massapequa school district to become principal of Gardiner Manor Elementary, where Bernagozzi taught third grade.

Shortly after Lenz started, she received a phone call from Bay Shore's personnel director, Manus O’Donnell, according to Lenz's testimony in the civil lawsuits.

In that conversation, O'Donnell asked Lenz if she knew the district twice investigated allegations that Bernagozzi sexually abused students, in 1971 and in the months before Lenz was hired, according to the deposition. No, Lenz hadn't been told that, and she said O’Donnell acted “shocked.” O’Donnell died in 2003.

Lenz, a first-time principal, responded to the O’Donnell call by embarking on a mission to educate herself on the facts surrounding all sexual abuse allegations.

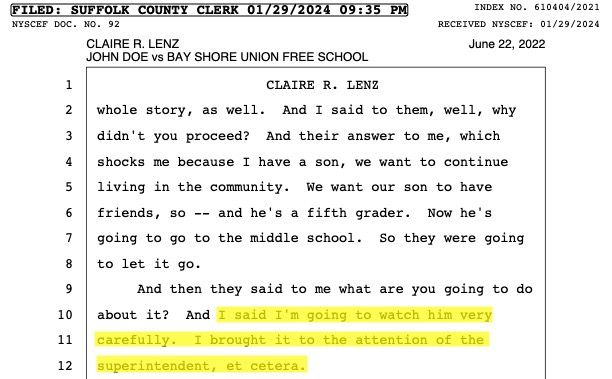

Lenz wrote down what O’Donnell told her about the district’s 1971 investigation. Then Lenz arranged a meeting with the parents who said Bernagozzi abused their son in a bathroom during an after-school program in the 1992-93 school year. She testified that the parents told her they dropped the charges because “we want to continue living in the community.”

“Then they said to me, ‘What are you going to do about it?’ And I said, ‘I'm going to watch him very carefully,’ ” Lenz testified. “I brought it to the attention of the superintendent.”

Like Lenz, Evelyn Holman also was new to Bay Shore, starting as superintendent in July 1994 after a decade as a superintendent in Wicomico County, Maryland.

Lenz called Holman in September and detailed the information she learned about Bernagozzi, according to court papers. “Be vigilant,” Holman told Lenz in response.

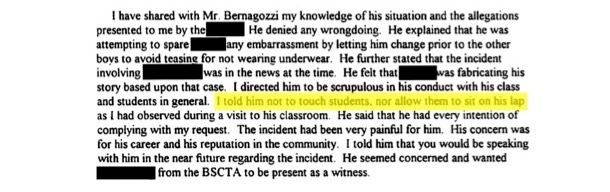

After the phone conversation, Lenz sent Holman a memo recapping her findings and summarizing her meeting with Bernagozzi.

Newsday obtained the memo from Suffolk Supreme Court. In it, Lenz wrote that Bernagozzi “denied any wrongdoing,” accused the boy of making up the allegations and explained that he brought the boy into the bathroom to spare him “any embarrassment by letting him change prior to the other boys to avoid teasing for not wearing underwear.”

It's not explained how and why Bernagozzi knew the boy was not wearing underwear.

Lenz also wrote: “I directed him to be scrupulous in his conduct with his class and students in general. I told him not to touch students, nor allow them to sit on his lap as I observed during a visit to his classroom.”

Lenz also barred Bernagozzi from continuing playing sports with children after school on school property, as records show he had done for many years. In addition, she testified that she regularly visited his classroom throughout the school year at various times of the day. She let him continue his class plays because rehearsals took place during the school day, when Lenz felt Bernagozzi could be monitored.

Lenz told Newsday she did not have the authority to remove Bernagozzi from the classroom herself.

"You have to go through the chain of command," said Lenz, 81, of Bradenton, Florida. "That was Holman's responsibility. That is the protocol."

Holman came to the conclusion “early on” in her tenure that Bernagozzi did not belong in the classroom, according to sworn testimony she gave during a nine-hour, two-day deposition in the civil lawsuits.

Holman, 82, of Bay Shore, spoke to Newsday in two hourlong phone interviews in recent weeks.

Holman said Lenz’s September 1994 memo compelled her to go back to O’Donnell to seek information regarding the 1971 investigation. O'Donnell told Holman the district investigation determined those allegations were "unfounded" and then "expunged" the documentation from his file, she said.

"I didn't know anything about this until I had been hired, obviously," Holman said by phone.

Seeking information about the more recent allegation against Bernagozzi, Holman called the previous superintendent, Bellamore. He told Holman only that everything had been “investigated and unfounded,” she said.

“That’s the limit of the information I got,” Holman said.

Holman said she "wanted [Bernagozzi] out of the area" but couldn’t remove him from the classroom because the district already had dealt with those allegations. Tensions between the district and the teachers union also were high at that time amid yearslong contract negotiations, Holman said.

What happened next between Holman and the union is in dispute.

At her January 2023 deposition, a lawyer asked Holman: “What conversations were you having with [union president] Don Reuss at the union about Mr. Bernagozzi? What was being discussed?”

Holman replied, “What was being discussed? Don Reuss was saying, 'Where's your proof?' Came out of his mouth every time he saw me, so where's your proof?”

Reuss disputed that when reached by Newsday last month at his Naples, Florida, home.

“I never spoke with Dr. Holman about Tom Bernagozzi,” Reuss, 80, said.

The union president from 1979 through 1999, Reuss said he never heard about sexual abuse allegations against Bernagozzi until he read about it in the news in recent months.

“It never came to the union,” he said. “We would have represented him. By law we were required to represent him. But we never had to.”

When Reuss' words were relayed to Holman last month, she said: "Oh, he's full of crap ... I can't believe that. I never gave him anything in writing, no, because I never got anything from these parents to give them something in writing."

Holman said she recalled a father in the late 1990s expressing concern to her directly about Bernagozzi's behavior with his son. She said the father's allegation did not rise to sexual abuse. She said he declined her repeated requests that he put his concerns in writing.

Holman said she had weekly informal conversations with Reuss over a drink on Wednesday nights to discuss contract negotiations, and she said she raised concerns about Bernagozzi during these meetings.

"Don Reuss did always say to me, 'Where's your proof? Where's your proof?' " Holman said. "And now he's acting like I never talked to him about it. Hmm."

Nearing the two-year anniversary of Lenz's hiring, she sent a follow-up memo to Holman about Bernagozzi in April 1996, saying, “I need your guidance and support in this matter.”

Lenz testified she caught Bernagozzi three times with children on his lap, and other times saw him holding hands with students. Each time, she said it was inappropriate, then documented what happened.

She placed those observations in an envelope, which she said she transferred to Bernagozzi’s file at the end of the year.

Bernagozzi’s 189-page personnel record, which Newsday obtained from Suffolk Supreme Court, includes letters Lenz wrote to him raving about the class plays and performance reviews that were all positive.

Missing, however, is the documentation she insists she placed there about any hand-holding or lap-sitting she witnessed. The district did not provide an explanation for the missing records in court papers.

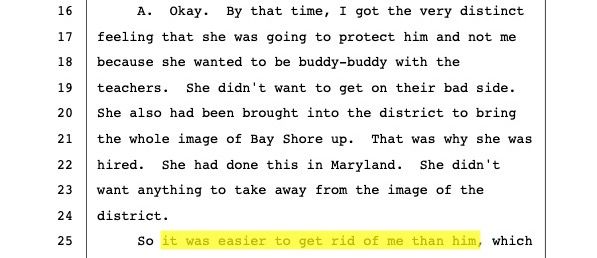

By the end of 1996, Holman removed Lenz as principal. She testified that she wanted a more experienced principal to manage Bernagozzi.

Lenz testified she believes Holman grew tired of her persistence that the superintendent deal with Bernagozzi.

“It was easier to get rid of me than him,” Lenz testified.

Holman said in response that if Lenz had done a better job of documenting Bernagozzi's insubordination — by continuing to have children on his lap against her wishes — Holman would have "proof" to bring to the union to potentially remove him from the classroom.

“If she would have told me, I would have fired him immediately, or put him on suspension to investigate," Holman said.

Lenz disputed this in her deposition, saying she placed her written observations of Bernagozzi with children on his lap in his file. She testified that she made sure her observations were still in Bernagozzi's file when she left in 1996.

Asked by phone if she had any regrets from her handling of Bernagozzi, Holman said:

"I regret having any little kid hurt, of course," she said. "Of course I took it very seriously. And I certainly tried to deal with it as much as I possibly could."

Holman added, "If I were the parent, he would be in deep trouble."

From his first days in the classroom, Bernagozzi developed a reputation as a warm, engaging leader whose teaching methods motivated children, charmed parents and impressed administrators.

His dedication to creating a distinctive and eccentric class culture resonates throughout his personnel records that were filed in court.

Bernagozzi’s class regularly performed plays, from classics such as "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory" to scripts he wrote himself. Twice a year, their plays entertained the elementary school during the day and followed with a nighttime performance for the community.

His classes took field trips to Manhattan, attending the "Nutcracker" at Lincoln Center, watching shows at Radio City Music Hall, and visiting the Museum of Natural History.

Bernagozzi’s students wrote letters to celebrities and professional athletes, and he boasted to parents that they received responses from Katharine Hepburn, Jane Fonda, Carol Burnett and Yankees and Islanders players.

“My travels to Spain, Mexico, France, England, Scotland, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, Canada and other locations have afforded me the opportunity to share many experiences and items with the children,” Bernagozzi wrote to incoming third-grade parents in September 1984.

He had big dreams — and he shared them with parents. He sent letters home about how he interviewed famed children’s author Roald Dahl, wrote a book he hoped to publish and served on the advisory board for Instructor Magazine and Scholastic.

In 1989, children’s author Judy Blume visited Bernagozzi’s class, posed for a photo with the exuberant teacher and took questions from his students. A magazine story written about the visit is in his personnel file.

In the classroom, he eschewed the use of textbooks, instead focusing on current events discussions, class contests, speeches and math games. His classroom published its own newspaper — The Times of 3BE — and their work regularly appeared in Kidsday, the long-ago page in Newsday that featured stories by school-age children.

“There were always your favorite teachers or teachers that you wanted, but this was different with him,” said Kristen Fraccalvieri, 42, who was in Bernagozzi’s class in 1989. “It was a coveted spot in his class.”

That summer, Fraccalvieri ran down the street waving her classroom assignment, ecstatic that the paper revealed she scored a seat in Bernagozzi’s class.

It’s the equivalent of winning the Gardiner Manor lottery in 1989 — learning that you’ll be attending third grade in the classroom that even had its own 3-BE nickname.

Bernagozzi also rewarded children through an All-Star chart on the classroom wall for all to see; Fraccalvieri recalls the male students always topped the list. A self-described “overachiever,” she felt frustrated that she rarely received the teacher's attention.

Individual achievements in class meant a child received a star on their chart — 100 stars earned them a trip for ice cream after school, he told parents in that 1984 letter.

“Kids looked forward to being in the classroom because you got to do a lot of cool stuff,” said S. Mark Rosenbaum, 76, of Port St. Lucie, Florida, the principal of Mary G. Clarkson Elementary from 1984-87.

The performance reviews Rosenbaum wrote about Bernagozzi for his personnel file are all positive.

“Bernagozzi gives willingly of his time, energy and skills in working with his youngsters after school, in presenting a superb annual Christmas play for the school, in service to the school and the district through his work on the Writing Committee, and in many other ways,” Rosenbaum wrote in 1985. “He is truly worthy of the title ‘Master Teacher.' ”

Bernagozzi regularly stayed after school to play sports with the boys. In a letter to a substitute teacher still in his personnel file, he detailed the classroom activities planned for the day — and said he’d be back at dismissal.

“I told the Gardiner Manor kids they could come for hockey today since I’ll be back,” he wrote. “I hope ... and ... and ... will be able to play.”

Rosenbaum said he knew Bernagozzi stayed after school with children also to do work on writing or to play sports with children. He considered the extra time with the children a positive.

“That was one of his drawing cards,” he said.

Anything Bernagozzi did with students away from school grounds didn’t require the principal’s approval, Rosenbaum said. “That was strictly between him and the parents,” he said.

Bernagozzi's attorney said in court in January that he had written permission from parents for those trips.

The community’s steadfast and buoyant support for Bernagozzi in the 1990s also frustrated Holman.

“I’ve never had a teacher that had so many letters of commendation and how wonderful this person is,” she testified.

She believed Bernagozzi encouraged parents to send her letters in support on his behalf. Likening Bernagozzi to a kid in school who desperately wants an A but does not want to put in the work, she said, “What in your ego makes you do that?”

Suffolk acting Supreme Court justice Karen Wilutis denied prosecutors' request to hold Bernagozzi without bail following his arrest, noting he has no prior criminal record. Bernagozzi's attorney said he lives alone and has dogs to care for.

Suffolk prosecutors said Bernagozzi used “the same common scheme or plan for 30 years” to sexually abuse his students.

According to prosecutors who brought the criminal charges and lawyers representing the men suing the district, Bernagozzi won the trust of parents to gain unfettered access to the children, then captivated the boys with his youthful charisma and rewards such as ice cream, games and his attention.

Newsday interviewed seven of the 45 men who filed lawsuits under the Child Victims Act alleging that Bernagozzi sexually abused them. Newsday does not identify victims of sexual abuse without their consent. Four of the men decided to use their names.

Their memories of the alleged abuse follow similar patterns, even as the allegations range from 1971 through 2001.

The seven said in interviews with Newsday, in their sworn testimony and in court filings that Bernagozzi inappropriately touched them during the school day while helping them change into costumes for play rehearsals, during private lunches in the classroom while the rest of the students ate in the cafeteria and under the guise of tucking in their shirts.

After school, they said Bernagozzi inappropriately touched them while they changed for their boys-only sports program that took place at the school and sometimes while he drove them home too.

Some of the men have succeeded in their careers. Others struggled with addiction and holding jobs and have criminal records. What they almost all have in common: They kept the alleged abuse a secret, until just recently.

“I thought I did something wrong for the longest time,” said C.J. Brandl, 46, of Bay Shore. “It’s shame — I’m ashamed of this. I buried this. I never, ever imagined speaking about this.”

Bernagozzi taught Brandl in 1986-87, and then taught his brother, Chris, the following school year.

Both Brandl brothers allege Bernagozzi sexually abused them. Both filed claims against the district.

Their shared traumatic experience at such a young age became a wedge in their relationship.

Toward the end of Chris' third grade year, the family spoke over dinner about Bernagozzi’s recommendation to hold Chris back in third grade, to stay another year in Bernagozzi’s class.

In the decades that have passed, C.J. viewed that dinner conversation with regret. Presented with an opportunity to speak up and put an end to the alleged abuse, he stayed silent.

“I couldn’t protect my brother,” C.J. said. “To this day it kills me.”

Both brothers said they’ve struggled with addiction for decades; they believe the alleged abuse started them on paths of self-destructive behavior.

C.J. said he’s been sober a year and seven months. Chris said he recently eclipsed two months and is living in a sober home. He faces open weapons and drugs charges in Suffolk district court, records show.

“I think drugs saved my life in the beginning because I think I would have killed myself, honestly, from all the [expletive] I was going through,” said Chris, 45. “People are like, what, how do you say that? But it's true because I just kept cramming it down, not talking about it.”

One third grade memory still haunts Chris.

A custodian walked into the classroom when Bernagozzi allegedly was inappropriately touching him in the back corner of the room during lunch.

Looking back now, Chris wonders if his third grade self was aware enough at that moment to think: “Finally, somebody is going to say something."

But, he said, nothing changed.

The news that Suffolk police arrested Bernagozzi and charged him set off a string of emotions among the men who filed claims.

Dr. Matthew Joseph Higgins, 55, a Bradenton, Florida-based anesthesiologist, alleges Bernagozzi repeatedly sexually abused him as a third-grader at Mary G. Clarkson Elementary in 1976-77. He struggled to emotionally process the experience of being violated as an 8-year-old, he said.

“I was ashamed," he said, "and I partly felt responsible for what had happened.”

Toward the end of the school year, Higgins screamed so loudly during nightmares that he awoke his sister, who called for his parents. Higgins then revealed the alleged abuse to them.

Higgins' father removed him from the district and enrolled him at a private elementary school. While the trauma went largely unspoken, it had a lifelong impact.

Higgins said he "fantasized" for decades about Bernagozzi one day getting arrested.

Higgins, who also filed a claim against the school district, is speaking out in hopes of inspiring other former Bay Shore students with similar experiences and also because he wants to send a message to Bernagozzi that “he didn’t wreck me.”

Hubbard, the security guard who made a scene at the school, described his reaction to the arrest as pure happiness, akin to someone winning the lottery.

“I hope he spends the rest of his life in a prison until he dies,” he said.

Hubbard feels victimized twice: first when Berganozzi allegedly sexually abused him in 1973, and then when he revealed his secret to the district in the mid-1980s and felt brushed aside.

The day after Hubbard’s outburst at the meet-the-teacher night, he visited the house of his boss, the district’s security director, John Thomas.

Hubbard said he then revealed for the first time in his life the details of the alleged abuse. He trusted Thomas and viewed him as a second father figure. Thomas worked by day for the Suffolk Police Department; Hubbard’s father also worked for Suffolk police.

“I’m going to report it,” Thomas said, and Hubbard believed him.

But months went by and nothing came of it. Hubbard checked in again, and still nothing. Finally, Thomas returned to Hubbard and said: “If you value this job, leave it alone. It happened a long time ago.”

“That's what he told me,” Hubbard said.

Thomas died in 2010.

Thomas’ son, Gordon, also worked as a Bay Shore security officer at the time.

“My father took it up the chain more than once, each time Robby brought it to him, he brought it up the chain, and they denied everything,” said Gordon, 66, of Bay Shore. “He went up the ladder and they brushed it off. They ignored it.”

The district declined to comment about the circumstances surrounding Hubbard's employment as a security guard.

For Hubbard and the others, the criminal charges, coupled with the 45 lawsuits against Bay Shore, serve as validation to their decades of suffering silently.

“It was a relief to know that somebody's finally listening,” Hubbard said. “Nobody would listen, and nobody would hear me.”

The Bay Shore district and its publicly elected board members have said little about the lawsuits in the three years since they were filed.

Superintendent Steven Maloney’s only expansive comment came in a Nov. 30 email to parents after Newsday mentioned the lawsuits in a story about the financial impact that Child Victims Act claims are having on Long Island districts.

“The lawsuits reported by Newsday pertain to accusations of sexual abuse that allegedly occurred decades ago, involving one former teacher who has not been employed by Bay Shore Schools since 2000,” Maloney said in a statement. “The District is presently proactively working with legal counsel to defend these lawsuits in order to ensure the least financial impact on our community.”

Christina Puccio, 45, of Bay Shore, told board members at a January meeting that their statement was “out of touch” and “insensitive.”

“I was shocked that the first public statement was about how the cost of this case will impact the taxpayers rather than immediately addressing the pain and suffering of the victims and assuring parents that nothing like this would ever happen again,” she added.

“How do you think the victims who are still deeply tied to this community felt reading this?” she asked.

Puccio also asked the board members to “create and implement a tangible plan that is made public sharing the policies that are in place to prevent any further abuse.”

The board members did not respond to her comments.

Tonya Wyss, 46, of Bay Shore, who also addressed the board of education, said the district has not publicly addressed its current policies designed to prevent sexual abuse.

"The Board of Education recognizes and understands the frustration the community may experience due to our inability to discuss this matter publicly," district spokeswoman Krystyna Baumgartner said. “However, the Bay Shore School District takes allegations of abuse very seriously and remains committed to the health, safety, and well-being of all students.”

In court, Bay Shore’s attorneys have defended the lawsuits by attempting to reduce the district’s potential liability.

In countersuits against Bernagozzi, the district argued that if a jury that rules in favor of a former student, it will be because of the retired teacher's “actions, omissions, recklessness, carelessness, and negligence.” No decision has been made.

The district failed to convince a judge to dismiss all abuse claims that took place off school property, arguing it should not be responsible for his alleged behavior away from school. More than half of the 45 lawsuits include allegations that took place off school grounds in addition to at the school.

Suffolk Supreme Court judge Leonard Steinman rejected the district's argument, writing in September, “The district had a duty to ensure that the pupils in its care were safe from the teachers they were instructed to obey and respect.”

The district asked a different judge in January to dismiss two of the cases because Bay Shore said those allegations represent “accidental or incidental touching” of the boys' genitals, as opposed to sexual abuse. The judge has not decided.

Sparked by what they believe to be a largely silent response from the district and board of education, a few community members organized a candlelight vigil at dusk on Feb. 9 for the purpose of “strength, healing, justice.”

Several dozen people attended.

Wyss helped organize the event. Bernagozzi ranked as her favorite, most influential teacher. Shortly before she graduated high school, she returned to his classroom and told the third-graders “how privileged they were to be in that room.”

The memory makes her emotional in light of Bernagozzi’s arrest. She wonders if any of the people who say Bernagozzi abused them were sitting in the classroom that day.

Said Wyss, “You almost have to rewrite your childhood.”

Holman, who retired in 2011 after 17 years as superintendent, added: "If more people had spoken up and followed through and all this, maybe we could have saved a few kids."

Hubbard, the former student who returned as a security guard, takes issue with that.

"I reached out when I was young," he said. "I reached out to try to stop this, you know, and it fell on deaf ears."

Robby Hubbard said he had buried his memories of third grade teacher Thomas Bernagozzi repeatedly sexually abusing him behind an obscured classroom window in 1973, never speaking of it to anyone.

But when he returned to the Bay Shore school district as a nighttime security guard more than a decade later, in the mid-1980s, and saw Bernagozzi at a meet-the-teacher night, he was overcome by rage. Stomping around, he waved his arms and loudly called Bernagozzi a “child molester.” He stopped only when a custodian physically ushered him away from parents and teachers.

“I just wanted to freaking kill him,” Hubbard, now 59, told Newsday in January in a conference room in Jacksonville, Florida, near his home in St. Augustine.

For months, Hubbard relentlessly pressed the district to investigate Bernagozzi, by then an award-winning teacher who was popular among students, parents and administrators.

Finally, the district told Hubbard to drop the issue. When he refused, he said they fired him from his part-time job “to get me to go away.”

Today, Suffolk prosecutors refer to Bernagozzi, 75, as “a serial child abuser” accused of sexually abusing scores of male students between the ages of 4 and 12 during a 30-year teaching career that ended in 2000.

“Unfortunately, the statute of limitations bars direct prosecution on most of the horrific conduct that has been inflicted upon many of the victims who have come forward,” Suffolk Assistant District Attorney Dana Castaldo said.

He pleaded not guilty in Suffolk Supreme Court in January to charges of sodomy and sexual conduct against a child involving two former students. He faces up to 25 years in prison on each charge. The single count of sodomy relates to a student who was 4 years old when Bernagozzi allegedly abused him from September 1989 to January 1990, court records state. The sexual conduct against a child charge involved a different student who was between 8 and 10 years old when Bernagozzi allegedly abused him from November 1997 to January 2000, the records show.

A Newsday investigation — following interviews with seven men who allege Bernagozzi abused them as youngsters, three administrators who oversaw Bernagozzi, and a review of thousands of pages of court and school documents — found that the district knew of at least five alleged incidents in 30 years of teaching, and documented red-flag behaviors such as having children on his lap in class. But the district never moved to terminate Bernagozzi, and Suffolk police said they have no record of being contacted.

Among Newsday's findings:

Robby Hubbard, left, with teacher Thomas Bernagozzi at Hubbard's pool birthday party at his house in Bay Shore in August 1974. Credit: Courtesy of Robbert Hubbard

- The district investigated an allegation of “pedophilia” in 1971, a year into Bernagozzi’s teaching career, and placed the documentation in a sealed envelope in his personnel file. By 1994, that envelope was missing from the file, according to a district memo Newsday obtained. District officials testified in depositions related to civil lawsuits against the district that they were told the allegations were determined in 1971 to be "unfounded."

- Two decades later, in 1992, Bay Shore suspended Bernagozzi while investigating an allegation he sexually abused a boy after school in a bathroom. A district memo Newsday obtained from court records said the boy’s parents dropped the allegations “at the suggestion of” then-Superintendent Crescent Bellamore because he said “the child would be subject to needless trauma.” Bellamore died in 2015. No records from that investigation exist, the district said.

- Parents of two boys reported separate abuse allegations to administrators at Bernagozzi’s elementary school in 1977 and 1987, according to court records and interviews. There is no evidence from the court file that the district investigated or took any action either time.

- Bernagozzi’s everyday interactions with boys raised concern among administrators. Principals told him to stop having kids sit on his lap in class as early as 1975 and again in 1994. Meanwhile, Bernagozzi regularly stayed after school with boys to play sports, often without shirts, took their pictures and regularly drove them home, according to court documents and interviews. He took boys on trips to the beach, ice skating, to a local fitness center, New York City and strawberry picking. School officials allowed these because they believed he had parental permission, records show.

- Bernagozzi retired in June 2000, then returned to Gardiner Manor Elementary the following school year as a substitute teacher and volunteer. However, a staffer’s memo in November 2000 detailed how he had taken a boy into a bathroom the previous March, when he still taught third grade. Then-Superintendent Evelyn Holman banned him from school property and ordered him to not contact students or their families, according to court documents.

Suffolk police arrested Bernagozzi at his Babylon home in December. He is free on a $600,000 bond and is due back in court March 19.

The allegations against Bernagozzi surfaced in 45 separate lawsuits filed against the Bay Shore school district between July 2020 and August 2021 under the Child Victims Act. State legislators in 2019 passed the act, which allowed childhood survivors of sexual abuse a one-year window to file a lawsuit for damages. Then-Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo extended the window a year, to August 2021, because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before the law's passage, survivors were prevented from filing suit once they turned 23.

The 45 suits, including one filed by Hubbard, are the most against any of Long Island’s 124 public school districts, according to Newsday's review of court records. Bernagozzi is central in all the suits.

Newsday does not identify victims of sexual abuse without their consent. Hubbard and three other men who filed lawsuits agreed to use their names in this story.

Bernagozzi “used his position of power, authority and trust over his victims and their families to gain access and [create] opportunities for the children to carry out these heinous acts,” Castaldo said.

The allegations in the lawsuits occurred in nearly every year Bernagozzi taught at Bay Shore’s Gardiner Manor and Mary G. Clarkson elementary schools. The district filed countersuits against Bernagozzi, arguing he should be held responsible instead of the school system.

Bay Shore Superintendent Steven Maloney and board president Jennifer Brownyard said in a joint statement that they are “constrained and unable to comment … due to pending and ongoing litigation.”

Bernagozzi did not return messages seeking comment for this story. He said in December that his Huntington-based attorney, Samuel DiMeglio, advised him not to speak to reporters. Asked for comment for this story, DiMeglio said, "We are not responding." DiMeglio said in Suffolk Supreme Court on Jan. 30 that Bernagozzi "vehemently denies the allegations."

The first trial in the civil lawsuits against the Bay Shore district begins April 2 in Suffolk Supreme Court.

The court records do not state how much money the plaintiffs are seeking from the district.

A Newsday investigation found dozens of school districts have paid millions to settle Child Victims Act lawsuits by former students who say teachers, administrators and fellow students sexually abused them. Including the claims against Bay Shore, 150 more lawsuits are ongoing.

A total of 27 school districts have settled 42 lawsuits for a combined $31.6 million, a Newsday analysis of court records shows.

'Be vigilant'

In the summer of 1994, the Bay Shore district hired Claire Lenz from the Massapequa school district to become principal of Gardiner Manor Elementary, where Bernagozzi taught third grade.

Shortly after Lenz started, she received a phone call from Bay Shore's personnel director, Manus O’Donnell, according to Lenz's testimony in the civil lawsuits.

In that conversation, O'Donnell asked Lenz if she knew the district twice investigated allegations that Bernagozzi sexually abused students, in 1971 and in the months before Lenz was hired, according to the deposition. No, Lenz hadn't been told that, and she said O’Donnell acted “shocked.” O’Donnell died in 2003.

Lenz, a first-time principal, responded to the O’Donnell call by embarking on a mission to educate herself on the facts surrounding all sexual abuse allegations.

Lenz wrote down what O’Donnell told her about the district’s 1971 investigation. Then Lenz arranged a meeting with the parents who said Bernagozzi abused their son in a bathroom during an after-school program in the 1992-93 school year. She testified that the parents told her they dropped the charges because “we want to continue living in the community.”

“Then they said to me, ‘What are you going to do about it?’ And I said, ‘I'm going to watch him very carefully,’ ” Lenz testified. “I brought it to the attention of the superintendent.”

Like Lenz, Evelyn Holman also was new to Bay Shore, starting as superintendent in July 1994 after a decade as a superintendent in Wicomico County, Maryland.

Lenz called Holman in September and detailed the information she learned about Bernagozzi, according to court papers. “Be vigilant,” Holman told Lenz in response.

After the phone conversation, Lenz sent Holman a memo recapping her findings and summarizing her meeting with Bernagozzi.

Newsday obtained the memo from Suffolk Supreme Court. In it, Lenz wrote that Bernagozzi “denied any wrongdoing,” accused the boy of making up the allegations and explained that he brought the boy into the bathroom to spare him “any embarrassment by letting him change prior to the other boys to avoid teasing for not wearing underwear.”

It's not explained how and why Bernagozzi knew the boy was not wearing underwear.

Lenz also wrote: “I directed him to be scrupulous in his conduct with his class and students in general. I told him not to touch students, nor allow them to sit on his lap as I observed during a visit to his classroom.”

Lenz also barred Bernagozzi from continuing playing sports with children after school on school property, as records show he had done for many years. In addition, she testified that she regularly visited his classroom throughout the school year at various times of the day. She let him continue his class plays because rehearsals took place during the school day, when Lenz felt Bernagozzi could be monitored.

Lenz told Newsday she did not have the authority to remove Bernagozzi from the classroom herself.

"You have to go through the chain of command," said Lenz, 81, of Bradenton, Florida. "That was Holman's responsibility. That is the protocol."

'Investigated and unfounded'

Holman came to the conclusion “early on” in her tenure that Bernagozzi did not belong in the classroom, according to sworn testimony she gave during a nine-hour, two-day deposition in the civil lawsuits.

Holman, 82, of Bay Shore, spoke to Newsday in two hourlong phone interviews in recent weeks.

Holman said Lenz’s September 1994 memo compelled her to go back to O’Donnell to seek information regarding the 1971 investigation. O'Donnell told Holman the district investigation determined those allegations were "unfounded" and then "expunged" the documentation from his file, she said.

"I didn't know anything about this until I had been hired, obviously," Holman said by phone.

Seeking information about the more recent allegation against Bernagozzi, Holman called the previous superintendent, Bellamore. He told Holman only that everything had been “investigated and unfounded,” she said.

“That’s the limit of the information I got,” Holman said.

Holman said she "wanted [Bernagozzi] out of the area" but couldn’t remove him from the classroom because the district already had dealt with those allegations. Tensions between the district and the teachers union also were high at that time amid yearslong contract negotiations, Holman said.

What happened next between Holman and the union is in dispute.

Thomas Bernagozzi at First District Court in Central Islip in December 2023. Credit: James Carbone

At her January 2023 deposition, a lawyer asked Holman: “What conversations were you having with [union president] Don Reuss at the union about Mr. Bernagozzi? What was being discussed?”

Holman replied, “What was being discussed? Don Reuss was saying, 'Where's your proof?' Came out of his mouth every time he saw me, so where's your proof?”

Reuss disputed that when reached by Newsday last month at his Naples, Florida, home.

“I never spoke with Dr. Holman about Tom Bernagozzi,” Reuss, 80, said.

The union president from 1979 through 1999, Reuss said he never heard about sexual abuse allegations against Bernagozzi until he read about it in the news in recent months.

“It never came to the union,” he said. “We would have represented him. By law we were required to represent him. But we never had to.”

When Reuss' words were relayed to Holman last month, she said: "Oh, he's full of crap ... I can't believe that. I never gave him anything in writing, no, because I never got anything from these parents to give them something in writing."

Holman said she recalled a father in the late 1990s expressing concern to her directly about Bernagozzi's behavior with his son. She said the father's allegation did not rise to sexual abuse. She said he declined her repeated requests that he put his concerns in writing.

Holman said she had weekly informal conversations with Reuss over a drink on Wednesday nights to discuss contract negotiations, and she said she raised concerns about Bernagozzi during these meetings.

"Don Reuss did always say to me, 'Where's your proof? Where's your proof?' " Holman said. "And now he's acting like I never talked to him about it. Hmm."

Insufficient documentation

Nearing the two-year anniversary of Lenz's hiring, she sent a follow-up memo to Holman about Bernagozzi in April 1996, saying, “I need your guidance and support in this matter.”

Lenz testified she caught Bernagozzi three times with children on his lap, and other times saw him holding hands with students. Each time, she said it was inappropriate, then documented what happened.

She placed those observations in an envelope, which she said she transferred to Bernagozzi’s file at the end of the year.

Bernagozzi’s 189-page personnel record, which Newsday obtained from Suffolk Supreme Court, includes letters Lenz wrote to him raving about the class plays and performance reviews that were all positive.

Missing, however, is the documentation she insists she placed there about any hand-holding or lap-sitting she witnessed. The district did not provide an explanation for the missing records in court papers.

By the end of 1996, Holman removed Lenz as principal. She testified that she wanted a more experienced principal to manage Bernagozzi.

Lenz testified she believes Holman grew tired of her persistence that the superintendent deal with Bernagozzi.

“It was easier to get rid of me than him,” Lenz testified.

Holman said in response that if Lenz had done a better job of documenting Bernagozzi's insubordination — by continuing to have children on his lap against her wishes — Holman would have "proof" to bring to the union to potentially remove him from the classroom.

“If she would have told me, I would have fired him immediately, or put him on suspension to investigate," Holman said.

Lenz disputed this in her deposition, saying she placed her written observations of Bernagozzi with children on his lap in his file. She testified that she made sure her observations were still in Bernagozzi's file when she left in 1996.

Asked by phone if she had any regrets from her handling of Bernagozzi, Holman said:

"I regret having any little kid hurt, of course," she said. "Of course I took it very seriously. And I certainly tried to deal with it as much as I possibly could."

Holman added, "If I were the parent, he would be in deep trouble."

'Master teacher'

From his first days in the classroom, Bernagozzi developed a reputation as a warm, engaging leader whose teaching methods motivated children, charmed parents and impressed administrators.

His dedication to creating a distinctive and eccentric class culture resonates throughout his personnel records that were filed in court.

Thomas Bernagozzi at Bay Shore's Gardiner Manor Elementary School in 1995. Credit: The Islip Bulletin

Bernagozzi’s class regularly performed plays, from classics such as "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory" to scripts he wrote himself. Twice a year, their plays entertained the elementary school during the day and followed with a nighttime performance for the community.

His classes took field trips to Manhattan, attending the "Nutcracker" at Lincoln Center, watching shows at Radio City Music Hall, and visiting the Museum of Natural History.

Bernagozzi’s students wrote letters to celebrities and professional athletes, and he boasted to parents that they received responses from Katharine Hepburn, Jane Fonda, Carol Burnett and Yankees and Islanders players.

“My travels to Spain, Mexico, France, England, Scotland, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, Canada and other locations have afforded me the opportunity to share many experiences and items with the children,” Bernagozzi wrote to incoming third-grade parents in September 1984.

He had big dreams — and he shared them with parents. He sent letters home about how he interviewed famed children’s author Roald Dahl, wrote a book he hoped to publish and served on the advisory board for Instructor Magazine and Scholastic.

In 1989, children’s author Judy Blume visited Bernagozzi’s class, posed for a photo with the exuberant teacher and took questions from his students. A magazine story written about the visit is in his personnel file.

In the classroom, he eschewed the use of textbooks, instead focusing on current events discussions, class contests, speeches and math games. His classroom published its own newspaper — The Times of 3BE — and their work regularly appeared in Kidsday, the long-ago page in Newsday that featured stories by school-age children.

“There were always your favorite teachers or teachers that you wanted, but this was different with him,” said Kristen Fraccalvieri, 42, who was in Bernagozzi’s class in 1989. “It was a coveted spot in his class.”

It was a coveted spot in his class.

Kristen Fraccalvieri, former student of Thomas Bernagozzi

That summer, Fraccalvieri ran down the street waving her classroom assignment, ecstatic that the paper revealed she scored a seat in Bernagozzi’s class.

It’s the equivalent of winning the Gardiner Manor lottery in 1989 — learning that you’ll be attending third grade in the classroom that even had its own 3-BE nickname.

Bernagozzi also rewarded children through an All-Star chart on the classroom wall for all to see; Fraccalvieri recalls the male students always topped the list. A self-described “overachiever,” she felt frustrated that she rarely received the teacher's attention.

Individual achievements in class meant a child received a star on their chart — 100 stars earned them a trip for ice cream after school, he told parents in that 1984 letter.

“Kids looked forward to being in the classroom because you got to do a lot of cool stuff,” said S. Mark Rosenbaum, 76, of Port St. Lucie, Florida, the principal of Mary G. Clarkson Elementary from 1984-87.

The performance reviews Rosenbaum wrote about Bernagozzi for his personnel file are all positive.

“Bernagozzi gives willingly of his time, energy and skills in working with his youngsters after school, in presenting a superb annual Christmas play for the school, in service to the school and the district through his work on the Writing Committee, and in many other ways,” Rosenbaum wrote in 1985. “He is truly worthy of the title ‘Master Teacher.' ”

Bernagozzi regularly stayed after school to play sports with the boys. In a letter to a substitute teacher still in his personnel file, he detailed the classroom activities planned for the day — and said he’d be back at dismissal.

“I told the Gardiner Manor kids they could come for hockey today since I’ll be back,” he wrote. “I hope ... and ... and ... will be able to play.”

Rosenbaum said he knew Bernagozzi stayed after school with children also to do work on writing or to play sports with children. He considered the extra time with the children a positive.

“That was one of his drawing cards,” he said.

Anything Bernagozzi did with students away from school grounds didn’t require the principal’s approval, Rosenbaum said. “That was strictly between him and the parents,” he said.

Bernagozzi's attorney said in court in January that he had written permission from parents for those trips.

The community’s steadfast and buoyant support for Bernagozzi in the 1990s also frustrated Holman.

“I’ve never had a teacher that had so many letters of commendation and how wonderful this person is,” she testified.

She believed Bernagozzi encouraged parents to send her letters in support on his behalf. Likening Bernagozzi to a kid in school who desperately wants an A but does not want to put in the work, she said, “What in your ego makes you do that?”

Suffolk acting Supreme Court justice Karen Wilutis denied prosecutors' request to hold Bernagozzi without bail following his arrest, noting he has no prior criminal record. Bernagozzi's attorney said he lives alone and has dogs to care for.

Same pattern of abuse

Suffolk prosecutors said Bernagozzi used “the same common scheme or plan for 30 years” to sexually abuse his students.

According to prosecutors who brought the criminal charges and lawyers representing the men suing the district, Bernagozzi won the trust of parents to gain unfettered access to the children, then captivated the boys with his youthful charisma and rewards such as ice cream, games and his attention.

Newsday interviewed seven of the 45 men who filed lawsuits under the Child Victims Act alleging that Bernagozzi sexually abused them. Newsday does not identify victims of sexual abuse without their consent. Four of the men decided to use their names.

Their memories of the alleged abuse follow similar patterns, even as the allegations range from 1971 through 2001.

The seven said in interviews with Newsday, in their sworn testimony and in court filings that Bernagozzi inappropriately touched them during the school day while helping them change into costumes for play rehearsals, during private lunches in the classroom while the rest of the students ate in the cafeteria and under the guise of tucking in their shirts.

After school, they said Bernagozzi inappropriately touched them while they changed for their boys-only sports program that took place at the school and sometimes while he drove them home too.

Some of the men have succeeded in their careers. Others struggled with addiction and holding jobs and have criminal records. What they almost all have in common: They kept the alleged abuse a secret, until just recently.

“I thought I did something wrong for the longest time,” said C.J. Brandl, 46, of Bay Shore. “It’s shame — I’m ashamed of this. I buried this. I never, ever imagined speaking about this.”

Bernagozzi taught Brandl in 1986-87, and then taught his brother, Chris, the following school year.

Both Brandl brothers allege Bernagozzi sexually abused them. Both filed claims against the district.

Their shared traumatic experience at such a young age became a wedge in their relationship.

Toward the end of Chris' third grade year, the family spoke over dinner about Bernagozzi’s recommendation to hold Chris back in third grade, to stay another year in Bernagozzi’s class.

In the decades that have passed, C.J. viewed that dinner conversation with regret. Presented with an opportunity to speak up and put an end to the alleged abuse, he stayed silent.

“I couldn’t protect my brother,” C.J. said. “To this day it kills me.”

I couldn't protect my brother ... to this day it kills me.

C.J. Brandl, brother of alleged victim of Thomas Bernagozzi

Both brothers said they’ve struggled with addiction for decades; they believe the alleged abuse started them on paths of self-destructive behavior.

C.J. said he’s been sober a year and seven months. Chris said he recently eclipsed two months and is living in a sober home. He faces open weapons and drugs charges in Suffolk district court, records show.

“I think drugs saved my life in the beginning because I think I would have killed myself, honestly, from all the [expletive] I was going through,” said Chris, 45. “People are like, what, how do you say that? But it's true because I just kept cramming it down, not talking about it.”

One third grade memory still haunts Chris.

A custodian walked into the classroom when Bernagozzi allegedly was inappropriately touching him in the back corner of the room during lunch.

Looking back now, Chris wonders if his third grade self was aware enough at that moment to think: “Finally, somebody is going to say something."

But, he said, nothing changed.

'He didn't wreck me'

The news that Suffolk police arrested Bernagozzi and charged him set off a string of emotions among the men who filed claims.

Dr. Matthew Joseph Higgins, 55, a Bradenton, Florida-based anesthesiologist, alleges Bernagozzi repeatedly sexually abused him as a third-grader at Mary G. Clarkson Elementary in 1976-77. He struggled to emotionally process the experience of being violated as an 8-year-old, he said.

“I was ashamed," he said, "and I partly felt responsible for what had happened.”

Mary G. Clarkson Elementary School in Bay Shore. Credit: Newsday/Erin Geismar

Toward the end of the school year, Higgins screamed so loudly during nightmares that he awoke his sister, who called for his parents. Higgins then revealed the alleged abuse to them.

Higgins' father removed him from the district and enrolled him at a private elementary school. While the trauma went largely unspoken, it had a lifelong impact.

Higgins said he "fantasized" for decades about Bernagozzi one day getting arrested.

Higgins, who also filed a claim against the school district, is speaking out in hopes of inspiring other former Bay Shore students with similar experiences and also because he wants to send a message to Bernagozzi that “he didn’t wreck me.”

Hubbard, the security guard who made a scene at the school, described his reaction to the arrest as pure happiness, akin to someone winning the lottery.

“I hope he spends the rest of his life in a prison until he dies,” he said.

Hubbard feels victimized twice: first when Berganozzi allegedly sexually abused him in 1973, and then when he revealed his secret to the district in the mid-1980s and felt brushed aside.

The day after Hubbard’s outburst at the meet-the-teacher night, he visited the house of his boss, the district’s security director, John Thomas.

Hubbard said he then revealed for the first time in his life the details of the alleged abuse. He trusted Thomas and viewed him as a second father figure. Thomas worked by day for the Suffolk Police Department; Hubbard’s father also worked for Suffolk police.

“I’m going to report it,” Thomas said, and Hubbard believed him.

But months went by and nothing came of it. Hubbard checked in again, and still nothing. Finally, Thomas returned to Hubbard and said: “If you value this job, leave it alone. It happened a long time ago.”

“That's what he told me,” Hubbard said.

Thomas died in 2010.

Thomas’ son, Gordon, also worked as a Bay Shore security officer at the time.

“My father took it up the chain more than once, each time Robby brought it to him, he brought it up the chain, and they denied everything,” said Gordon, 66, of Bay Shore. “He went up the ladder and they brushed it off. They ignored it.”

The district declined to comment about the circumstances surrounding Hubbard's employment as a security guard.

For Hubbard and the others, the criminal charges, coupled with the 45 lawsuits against Bay Shore, serve as validation to their decades of suffering silently.

“It was a relief to know that somebody's finally listening,” Hubbard said. “Nobody would listen, and nobody would hear me.”

It was a relief to know that somebody's finally listening.

Robby Hubbard, alleged victim of Thomas Bernagozzi

'Out of touch'

The Bay Shore district and its publicly elected board members have said little about the lawsuits in the three years since they were filed.

Superintendent Steven Maloney’s only expansive comment came in a Nov. 30 email to parents after Newsday mentioned the lawsuits in a story about the financial impact that Child Victims Act claims are having on Long Island districts.

“The lawsuits reported by Newsday pertain to accusations of sexual abuse that allegedly occurred decades ago, involving one former teacher who has not been employed by Bay Shore Schools since 2000,” Maloney said in a statement. “The District is presently proactively working with legal counsel to defend these lawsuits in order to ensure the least financial impact on our community.”

Christina Puccio, 45, of Bay Shore, told board members at a January meeting that their statement was “out of touch” and “insensitive.”

“I was shocked that the first public statement was about how the cost of this case will impact the taxpayers rather than immediately addressing the pain and suffering of the victims and assuring parents that nothing like this would ever happen again,” she added.

“How do you think the victims who are still deeply tied to this community felt reading this?” she asked.

Puccio also asked the board members to “create and implement a tangible plan that is made public sharing the policies that are in place to prevent any further abuse.”

The board members did not respond to her comments.

Tonya Wyss, 46, of Bay Shore, who also addressed the board of education, said the district has not publicly addressed its current policies designed to prevent sexual abuse.

"The Board of Education recognizes and understands the frustration the community may experience due to our inability to discuss this matter publicly," district spokeswoman Krystyna Baumgartner said. “However, the Bay Shore School District takes allegations of abuse very seriously and remains committed to the health, safety, and well-being of all students.”

In court, Bay Shore’s attorneys have defended the lawsuits by attempting to reduce the district’s potential liability.

In countersuits against Bernagozzi, the district argued that if a jury that rules in favor of a former student, it will be because of the retired teacher's “actions, omissions, recklessness, carelessness, and negligence.” No decision has been made.

The district failed to convince a judge to dismiss all abuse claims that took place off school property, arguing it should not be responsible for his alleged behavior away from school. More than half of the 45 lawsuits include allegations that took place off school grounds in addition to at the school.

Suffolk Supreme Court judge Leonard Steinman rejected the district's argument, writing in September, “The district had a duty to ensure that the pupils in its care were safe from the teachers they were instructed to obey and respect.”

The district asked a different judge in January to dismiss two of the cases because Bay Shore said those allegations represent “accidental or incidental touching” of the boys' genitals, as opposed to sexual abuse. The judge has not decided.

Sparked by what they believe to be a largely silent response from the district and board of education, a few community members organized a candlelight vigil at dusk on Feb. 9 for the purpose of “strength, healing, justice.”

Several dozen people attended.

Community members hold a candlelight vigil in support of those accusing Thomas Bernagozzi of sexually abusing them as children, in Brightwaters in February. Credit: Newsday/Steve Pfost

Wyss helped organize the event. Bernagozzi ranked as her favorite, most influential teacher. Shortly before she graduated high school, she returned to his classroom and told the third-graders “how privileged they were to be in that room.”

The memory makes her emotional in light of Bernagozzi’s arrest. She wonders if any of the people who say Bernagozzi abused them were sitting in the classroom that day.

Said Wyss, “You almost have to rewrite your childhood.”

Holman, who retired in 2011 after 17 years as superintendent, added: "If more people had spoken up and followed through and all this, maybe we could have saved a few kids."

Hubbard, the former student who returned as a security guard, takes issue with that.

"I reached out when I was young," he said. "I reached out to try to stop this, you know, and it fell on deaf ears."

This is a modal window.

Man shot in North Amityville ... School marijuana suspect in court ... LI Works: Making pizza at Umberto's ... What's up on LI

This is a modal window.

Man shot in North Amityville ... School marijuana suspect in court ... LI Works: Making pizza at Umberto's ... What's up on LI

Most Popular