When the Long Island Museum in Stony Brook was closed to visitors by the pandemic, the curators took advantage of the lull to organize its archives, some 220 linear feet of materials documenting New York and Long Island history.

There last summer curator Jonathan Olly discovered something startling: an uncataloged letter written by the head of what modern historians have called the Culper Spy Ring — which operated on Long Island and in Manhattan during the American Revolution to supply intelligence on British military activity to Gen. George Washington — to his chief agent in the city.

The letter from Continental Army Maj. Benjamin Tallmadge to Robert Townsend on Nov. 8, 1779, had been donated to the museum in 1951 — then mostly overlooked.

Its discovery fills a gap in the story of the intelligence network that has long captivated history buffs — even more so in recent years because of new books and the popular, if historically flawed, AMC series "Turn."

The letter is the only known surviving communication sent by Tallmadge (code-named John Bolton) to Townsend (code-named Culper Junior) because Townsend is believed to have destroyed all of the other letters written to him to prevent the British from learning his identity. The rediscovered document brings to 193 the number of known surviving Culper letters, according to Claire Bellerjeau, historian at Raynham Hall Museum, Townsend’s former home in Oyster Bay.

"What an exciting discovery!" Bellerjeau said. "This letter is quite unique: It is the only surviving letter I know of from Tallmadge to Townsend. And it’s also unique because it’s the only known letter dealing exclusively with a private business deal. It also is fascinating because it deals with the use of invisible ink."

Olly, who has worked at the museum for five years after having been on staff or interned at eight other institutions including the Smithsonian Institution while or since earning a doctorate in American studies from Brown University in 2013, said that "during the pandemic, with the museum not opening any new exhibits in 2020, the curatorial staff focused on collections management." Four curators concentrated on updating inventories from the 1950s through the 1970s that are recorded in ledgers.

'It was a surprise'

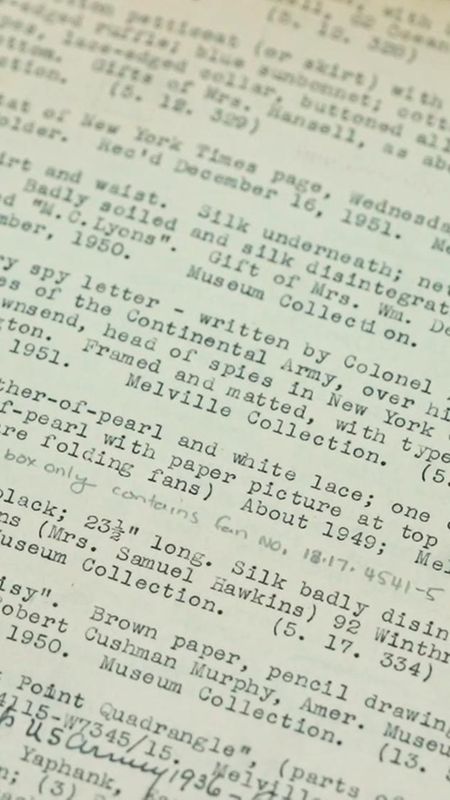

In August, Olly was examining a ledger from 1951. "I was actually looking up something else when I happened to look at the page in the ledger, and it said ‘Revolutionary spy letter written by Col. Benjamin Tallmadge, chief spy for the Continental Army … to Robert Townsend, spy in New York City … received December 1951.’

"It was a surprise because we didn’t believe we had anything connected to the Culper Spy Ring," the curator said, noting the importance of nearby Setauket as the waypoint for messages making their way from New York, then by whaleboat to Connecticut and on to George Washington. The 1951 ledger entry led him to the letter, tucked in a box with other manuscript materials.

"Unfortunately, it doesn’t say who it was received from," Olly said. He noted it was probably a gift from philanthropist Ward Melville, a founder of the museum and avid collector of Long Island artifacts who donated much of his collection to the institution, which opened in 1939 as the Suffolk Museum.

The letter and a transcription had been mounted on an acid-free mat, likely in the 1970s, Olly said, because that material would not have been available two decades earlier. There is no record the letter was ever displayed.

"We were quite happy," Olly said, "but it also raised the question ‘Is this real?’"

To answer that question, the museum reached out to Peter Klarnet, a rare manuscripts expert at Christie’s, the auction house in Manhattan. After examining the letter last November, he wrote: "I can state that, in my professional opinion, this is a period letter written by Benjamin Tallmadge in his capacity as Washington’s spymaster. I am also unaware of any 'Jno [John] Bolton' letters written to Robert Townsend (aka 'Culper, Jr.') in other repositories."

Although the museum declined to provide Klarnet's estimate of the letter’s value, Stony Brook University has purchased two Culper letters, paying $96,000 for one in 2006 and $60,000 for another in 2009.

The new letter, which had been folded into nine squares, was covered on both sides with a fine silk mesh, a process used in the early 20th century to preserve fragile documents. The museum hired Reba Fishman Snyder, a paper conservator at the Morgan Library in Manhattan, to remove the silk for better viewing and conserve the letter. The letter will be framed so it can be viewed on both sides.

A public viewing

The museum will display the letter on its website, longislandmuseum.org, starting March 28. Limited in-person viewing is set to begin on Culper Spy Day, Sept. 18.

In the letter, partially written in code, Tallmadge revisits a previous inquiry about whether Townsend, a merchant in Manhattan, could acquire silk and other expensive fabrics for him without endangering himself. Tallmadge also reminds Townsend not to use scarce invisible ink for communication not connected to intelligence gathering.

Tallmadge’s letter is signed with his code name, John Bolton, and labeled "No. 16." Spy ring members numbered the letters so the recipients could track whether one was lost or fell into British hands.

The letter reads in part:

Some time ago I proposed a certain affair to you, & directed you not to write me an answer with the Stain [invisible ink], as it might possibly expose us, I having none of the Counterpart [the liquid to reveal the invisible ink] then on hand. Not long since I rec’d a line from you written with the Stain, which I luckily discovered to be of a private nature, having a little of the counterpart on hand.

The coded section of the letter was deciphered by Bellerjeau and Kristen J. Nyitray, director of Special Collections and University Archives at Stony Brook University. The coded section reads:

What I wish to know of you is whether 707 [you] can 640. [transport] 1 [a] few Umcou [silks], Aewtiu [gauzes] 5 [and]: such costly articles from 727. [New York] 634. [to] 707 [you] without 132 [danger]. I also wish to know what relation 625. [the] 75 [cost] of such articles bears now 634. [to] their 75 [cost] before 625. [the] 680 [war].

As soon as you resolve me in these Questions I will write you more fully on the Subject. I write this in plain Style as I am informed C-[ulper] Sen’r [chief spy Abraham Woodhull of Setauket] is to have an interview with you and can deliver it himself. I should be glad of an answer by the Return of the Bearer.

I must again remind you not to write to me on private business with the Stain, as I have none of the Counterpart to decipher it & of course it must go on to 711. [Washington]

I have the Stain and can write you with that, but your private Letters to me must be wrote for the present with the Dictionary [Culper Code].

Bellerjeau noted that Woodhull wrote to Tallmadge on Nov. 5, 1779, that he: "Shall see Culper, Junr. on the 10th."

Then Woodhull wrote again from his Setauket farm to Tallmadge on Nov. 13 that "on the 10 was to see C. Jur. at a house he appointed twelve miles west from here …. To my great mortification Culper Jur. did not come that day ..."

Bellerjeau said "the meeting on Nov. 10 did not take place as planned, so Abraham Woodhull went home and never delivered this letter to Robert. This could be why the letter survived."

"Silks and gauzes were fine fabrics," she explained, surmising Tallmadge may have wanted to convert them into cash to support the war effort.

Spy ring's hard start

Little was known about the Culper network's operation until Suffolk County historian Morton Pennypacker identified the principals in the 1930s and proved, through document analysis, that Robert Townsend was Culper Junior.

After operating with little useful intelligence before and after the Battle of Long Island in late August 1776, Continental Army commander George Washington directed several attempts by military officers and civilians to create a spy network. The early results were not promising as evidenced by the capture and hanging of Nathan Hale after he came ashore in Huntington in September 1776.

Eventually, Washington turned to Tallmadge, a Yale University graduate and schoolteacher who became an officer in a Connecticut cavalry regiment and who had been the liaison between the general and the early intelligence chiefs. The messages for Washington from Long Island were transported from Setauket to Connecticut by whaleboat captain Caleb Brewster, a friend and early classmate of Tallmadge. Even before formation of the Culper ring, Brewster, who became a captain in the Continental Army, had volunteered to provide Washington with intelligence of British military activity on Long Island and the Sound. His unsolicited Aug. 7, 1778, letter to Washington could be considered the start of the ring, Bellerjeau said.

Letters from Tallmadge and his childhood friend Abraham Woodhull, a Setauket farmer and sometime smuggler who would become the chief spy coordinating with Tallmadge, demonstrate that the espionage operation was in full operation by October 1778.

Legend has it that Washington devised "Culper" as the name for the chief spy as a contraction of Culpeper County, where the army commander had worked as a surveyor in Virginia when he was 17.

Sometime in fall 1778 Woodhull began traveling to Manhattan and reporting to Brewster what he observed. He repeatedly beseeched Tallmadge and Washington to destroy his letters upon receipt. Yet most survived.

Afraid of traveling to New York after being stopped and questioned by British sentries, Woodhull recruited Townsend, purchasing agent in Manhattan for his father, Samuel, a prosperous Oyster Bay merchant and leading Patriot. To protect himself, Townsend adopted the alias "Culper Junior" because Woodhull was already Samuel Culper.

To avoid areas where interception and capture were more likely, agents and couriers carried intelligence reports from New York City across the East River, then 55 miles east on Long Island to Setauket, across Long Island Sound and then west along the Connecticut shore to Tallmadge and, ultimately, to Washington, either north of the city or in New Jersey.

History and legend

As the war persisted, the spy ring increased security by substituting numbers for people, places and things in a system devised by Woodhull in April 1779. Tallmadge upgraded the system in July by creating a "dictionary" of vastly expanded code.

The last — and best — layer of security was using a "stain," or special ink, that was invisible until treated with another solution.

The spy ring’s history has been romanticized and embellished, legend converted to fact by some authors and especially "Turn." One of the best-known aspects of the Culper Spy Ring story may be the purported role of Anna Strong’s clothesline. According to family tradition, Anna Smith Strong, Woodhull's neighbor and close friend, would hang laundry out to dry in a pattern to indicate in which cove Woodhull should meet Brewster. Yet, this arrangement is not mentioned in any of the letters; the only documentation is the story handed down through the Strong family.

While such debate will likely never cease, historians are thrilled that the new letter has surfaced.

"People always talk about how history is static and doesn’t change," said Beverly Tyler, historian at the Three Village Historical Society in Setauket who has researched the spy ring since the 1970s. "History is completely fluid. New documents give us new ideas. This letter is a perfect example of that."

Between the lines

Analysis and transcription of the 1779 letter from Benjamin Tallmadge to Robert Townsend created by Claire Bellerjeau and Kristen Nyitray. The letter will be on virtual display beginning March 28 at the Long Island Museum.

Page 1:

No. 16 Novr. 8, 1779

Sir:

Some time ago I proposed a certain affair to you, & directed

you not to write me an answer with the Stain [invisible ink], as it

might possibly expose us, I having none of the Coun-

terpart [liquid to reveal the invisible ink] then on hand. Not long since I rec’d a line from

you written with the Stain, which I luckily discovered to

be of a private nature, having a little of the counterpart

on hand.

What I wish to know of you is whether 707 [you] can 640. [transport] 1 [a] few

Umcou [silks], Aewtiu [gauzes] 5 [and]: such costly articles from 727. [New York] 634. [to] 707 [you]

without 132 [danger]. I also wish to know what relation 625. [the] 75 [cost]

of such articles bears now 634. [to] their 75 [cost] before 625. [the] 680 [war].

As soon as you resolve me in these Questions I will

write you more fully on the Subject. I write this in

plain Style as I am informed C -[ulper] Sen’r is to have an interview

with you and can deliver it himself. I should be glad

of an answer by the Return of the Bearer.

I must again remind you not to write to me on

private business with the Stain, as I have none of the

Page 2:

Counterpart to decipher it & of course it must go on to 711. [Washington]

I have the Stain and can write you with that, but your private

Letters to me must be wrote for the present with the Dic-

tionary [Culper Code].

I wish in future you would give some distinguishing

mark to the Sheet which is the true Letter to 711 [Washington] when it

comes in a Quire,* as I may possibly send the wrong

one to 711 [Washington].

Let what I have wrote here be a profound

Secret with yourself & C[ulper] Senior.

I am yours sincerely,

Jno. Bolton [Benjamin Tallmadge]

* It was Robert Townsend’s method to use the invisible ink by writing a whole letter on a blank page and inserting it into a full pack of new paper, a Quire. He called these “blanks” and sold them through his store in Manhattan. In this letter Tallmadge is asking Townsend to mark the invisible-ink letter so he can more easily find it in the pack.

Giving back to place that gave them so much ... Migrants' plight ... Kwanzaa in the classroom ... What's up on LI ... Get the latest news and more great videos at NewsdayTV