Before Steven A. Cohen used his intuitive mind and steely nerve to create a career on Wall Street, become unfathomably wealthy and purchase the New York Mets, he put those skills to work at the poker table in a friend’s basement in the early 1970s.

On summer nights, he and his crew from Great Neck North High School gathered at Kenny Ginsburg’s house. The stakes were not high. Just a dollar bet here and quarter raise there, bigger as they got better. Their variant of choice: seven-card stud with a high-low split, in which the person with the worst hand gets half the pot.

Ginsburg’s mom, who sometimes joined in, was OK with them regularly coming over to play cards because it meant these teenagers weren’t who-knows-where doing who-knows-what. The games sometimes lasted till sunrise, including one marathon session after which Cohen arrived home at 7 a.m. — right as his father, Jack, was readying to go to work.

"Steve said, ‘I just went up to get the paper for you, Dad,’ " Ginsburg recalled with a laugh. "I think his dad knew the truth, but he didn’t care."

More often than not, in those wee morning hours, Cohen won his friends’ money.

"What you learn is," said Billy Omeltchenko, another friend and poker participant, "Steve was great at reading people."

Steve Cohen, fourth from the left in the front row, in the 1974 yearbook photo of the Great Neck North High School boys basketball team. Billy Omeltchenko is third from the left in the top row. Credit: Great Neck North High School

More often than not, after he won his friends’ money, he let them off the hook.

"None of us had the money," Ginsburg said. "It tended to be ‘IOU.’ If he won and people owed him, he let them go. He was a pretty generous guy."

"It sounds silly," he continued. "But if you can’t play poker, you can’t trade [stocks], because it’s a risk game. You have to be able to take calculated risks. If people don’t have the stomach . . . "

Cohen had the stomach. Still does.

They might not have known it at the time, but poker offered a glimpse at who Cohen was and who he would become as a Long Islander, as a Wall Street giant and as a baseball fan.

Interviews and conversations with over a dozen of his friends, business associates and acquaintances reveal common threads woven through then, now and in between.

He is tough when he wants to be, gracious to those he knows, wicked smart, bold enough to flirt with trouble and savvy enough to avoid the worst of it.

Cohen, 64, declined an interview request for this article.

Steve Cohen, the Long Islander

Of all the dollars Cohen ever made, Brock Lownes was there for the first.

They met when they were 6 and lived down the block from each other. As preteens, they had the great idea of grabbing shovels on snowy days and walking the neighborhood to offer their services — for a price, of course. Other times, they’d wait outside the Gristedes supermarket, volunteer to carry a woman's bags to her car and hope for a tip.

Yes, the entrepreneurial spirit was strong with this one.

"He took it from there," Lownes said.

Such was Cohen’s middle-class, happily uneventful childhood on Lawson Lane. Born in 1956, he was the third of eight children for parents Jack, who ran a company that made dresses in the Garment District, and Patricia, a piano teacher, who raised their family in a home just a few minutes by foot from the middle and high schools.

"He was not born with a silver spoon in his mouth," said Rich Mendelsohn, Cohen’s classmate at Great Neck North and in college at the University of Pennsylvania. "That probably helped feed his motivation to be successful. He felt a responsibility. He’s quietly taken care of a lot of family members along the way."

These days, Cohen’s Long Island time is spent mostly in his large Hamptons houses. His full-time residence is in Greenwich, Connecticut, where he lives with his wife, Alex, his in-laws and some of his seven children: two from his first marriage, four with Alex and one stepchild.

Great Neck, though, was where he learned to love baseball, made lifelong friends and developed an interest in the stock market.

His fledgling youth baseball life — Memorial Field is less than a mile from where he grew up — ended with a shoulder injury. In high school, he carved out a notable athletics career for the Great Neck North Blazers, graduating in 1974.

Cohen was on the basketball team with Omeltchenko, who went on to play at Princeton. But his best sport was soccer. Omeltchenko was the center forward, Cohen his right wing. Donning a shoulder-length mane of shaggy dark hair, Cohen — who is bald now — scored 10 goals his senior year, tied with his friend for the most on the team. The Class of 1974 yearbook called them "strong offensive talents."

Of those Cohen tallies, the most memorable to Omeltchenko, nearly a half-century later? Under the lights at Hofstra during the playoffs, with Great Neck North down by one.

"I missed a penalty kick five minutes earlier that could’ve tied the game," Omeltchenko said, laughing. "That’s why I remember. He bailed me out."

Through those early years, Cohen became a man of many monikers. "Stevie" is the oldest and simplest; some friends still call him that despite the displeasure of Alex, who notes that his name is Steve. Then there is "Pig-Pen," like the "Peanuts" character, though he didn’t pick up that nickname until college, when his dorm room was reputed to be not the neatest. And some preferred "Sam" or "Sammy" because his golf swing was sweet like Sam Snead, tied with Tiger Woods as the winningest player in PGA history.

"He does have a very sweet golf swing," Mendelsohn said, noting Cohen's upper-echelon competitiveness.

The 1974 Great Neck North High School yearbook photo of Steve Cohen, who bought the New York Mets in 2020 for more the $2.4 billion. Credit: Great Neck North High School

An estimated $14 billion fortune has not been enough to drive Cohen from his roots. He not only attended his 40th high school reunion in 2014 — even volunteering his mansion before thinking better of it — but he also was one of the last to leave. To celebrate a round-number birthday or anniversary, he has been known to pay for a dozen or so couples to go on a cruise or trip with him and his wife.

Mendelsohn and Omeltchenko are part of a smaller gang, mostly from Great Neck, that still gets together when circumstances allow, usually a couple of times per year. Their go-to: Peter Luger Steakhouse in Great Neck.

"We joke about how some of the guys now have to take their dose of Lipitor before we go out for that meal," Mendelsohn said.

Cohen, who owns about $1 billion worth of art, is the same old Stevie when he hangs around them.

"I think he likes the fact that in his eyes and in our eyes, we’re still the same people we were in high school and college," Mendelsohn said. "We don’t need him to do anything for us. He gets plenty of that in his day-to-day life."

Omeltchenko added: "He hasn’t changed. To this day, he’s a regular guy."

Cohen’s investing success does not come as a huge surprise to those who have known him this long. Even as a kid, he had an odd passion for it.

He habitually read newspapers to examine the list of stocks, noting which went up and which went down the day prior. In an eighth-grade introduction to business class, in which the students chipped in to purchase a stock, he insisted they buy Perkin-Elmer, a global corporation with a wide-range of products and services. As a senior, when he was allowed to go off campus for lunch, he visited a nearby brokerage house, just sitting and watching the ticker tape.

"If he wasn’t wealthy, he’d be a little bit crazy," Mendelsohn said. "But when you’re really, really wealthy and you’re like that, you become eccentric."

Steve Cohen, the Wall Street giant

The last time the Mets won the World Series, 1986, was the first time Cohen was involved in an insider-trading investigation.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission subpoenaed Cohen, then 30 years old, because it was investigating a stock he purchased right before a takeover was announced, according to the book "Black Edge," published in 2017 and written by Sheelah Kolhatkar, a staff writer at The New Yorker who covers finance and other topics. It is the definitive chronicling of Cohen’s rise to prominence and the ensuing government Wall Street crackdown and draws its name from the industry’s term for inside information, which is illegal to trade on.

In the 1986 case, Cohen gave a 20-minute deposition during which he invoked the Fifth Amendment, which protects people from being forced to provide incriminating information about themselves. He was never charged. But that episode set the stage for his career as a Wall Street titan, which earned him the 36th spot on Forbes' 2020 list of the 400 wealthiest Americans.

Coming out of Penn's Wharton School in the late 1970s, Cohen was hired at Gruntal & Co., a brokerage firm. He was a phenom, ascending from underling to star over his 14 years there.

"He had tremendous skill at reading the tape," said Ginsburg, the poker host who joined Gruntal in the mid-1980s, after Cohen began to establish himself. "His timing was superb. Plus taking the risk and having the courage of your convictions and making the plays in what he thought was right."

Steve Cohen as chairman and chief executive officer of SAC Captial Advisors LP at the Robin Hood Veterans Summit in New York on May 7, 2012. Credit: Bloomberg/Scott Eells

In 1992, Cohen left Gruntal to start his own hedge fund, SAC Capital Advisors, named after his initials. That is where the wunderkind became a legend.

Cohen became known for his relentlessness. Every Sunday, Omeltchenko said, Cohen got a jump-start on the workweek by having his traders call him with their best ideas for the coming days. When he traveled, no matter where, he sent ahead a team to set up a temporary office, so he could work while he ostensibly was on vacation.

"Always," said Larry Foley, a SAC employee from 1994-2008. "When I go, I feel like, 'oh [expletive], he’s working, I’m not. I’m with him.' But you know something? He doesn’t hold that against me. He knows how he’s wired. He knows how I’m wired."

Foley left to start his own hedge fund but remains friends — and golf buddies — with Cohen. He described him as self-deprecating and quick-witted, not a micromanager, uninterested in wearing suits, willing to adapt and happy when his people work hard.

"Steve Cohen, the myth of a great trader, is more a great businessman and a good leader," Foley said.

Said Omeltchenko, whom Cohen hired in the mid-2000s as co-head of trading: "He was demanding but fair. He had such a disciplined approach, one of the hardest-working people I’ve dealt with. He is so prepared for all the different contingencies. He surrounds himself with very bright people, but they’re all accountable. When Steve was willing to spend money, he spent it wisely."

Those are kinder characterizations than the one in "Black Edge." In the subtitle, Kolhatkar refers to Cohen as "the Most Wanted Man on Wall Street." Based on years of reporting and hundreds of interviews, the book paints Cohen as an obsessive genius of a trader who is comfortable with massive risks, a demanding boss who created an extremely high-pressure, win-at-all-costs work environment with lots of turnover — and, given the considerable compensation, lots of people who wanted to work there.

A piece of that environment, according to Kolhatkar’s book: Cohen devised a system in which employees would recommend trades to him and assign it a number, 1-10, based on how confident they were. When an idea got a nine or 10, it meant the employee was very or absolutely convinced it was a good idea — which is awfully difficult in the unpredictable world of the stock market. Cohen did not ask why they were confident. He just knew that they were. That gave him plausible deniability if the idea stemmed from black edge.

SAC’s success, including annual returns widely reported to average 20-30%, got the attention of the SEC and the FBI. Cohen's company became the target of a nearly decade-long insider-trading investigation. One of his portfolio managers, Mathew Martoma, was found guilty of two counts of securities fraud and one count of conspiracy to commit securities fraud and was sentenced to nine years in prison in 2014.

SAC, as an institution, pleaded guilty to criminal insider-trading charges (four counts of securities fraud and one count of wire fraud) and paid a record $1.8 billion penalty. The company’s culture led to "insider trading that was substantial, pervasive and on a scale without known precedent in the hedge fund industry," federal prosecutors said in a July 2013 indictment. The plea agreement was announced four months later.

Cohen, as an individual, was never charged with a crime. But he was barred from supervising any broker, dealer or investment adviser for two years after the SEC came at him with a lesser civil case for failing to properly manage an employee, Martoma.

"Cohen ignored red flags indicating that Martoma might have access to material nonpublic information," the SEC said in a 2016 filing when it accepted Cohen’s settlement offer. "Despite receiving red flags, Cohen failed to take prompt action to determine whether Martoma was engaged in unlawful conduct and failed to take reasonable steps to prevent violations of the federal securities laws."

Preet Bharara, the former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, declined to comment for this story. Several other senior government officials involved with the case also declined to comment or did not respond to interview inquiries.

Cohen rebranded his company as Point72 Asset Management, a nod to the address of the firm’s main office: 72 Cummings Point Road in Stamford, Connecticut. It has more than 1,600 employees and manages $18.9 billion as of October, according to its website.

Steve Cohen, the baseball fan (and owner)

Central to Cohen refurbishing his image by becoming the Mets’ savior is the detail that he is a lifelong fan of the team. He gets Mets fans, wants to help Mets fans, because he is one — just a really, really, really rich one.

His first Mets games were at the Polo Grounds. He lists Cleon Jones’ dropping-to-a-knee catch and Mookie Wilson’s grounder through Bill Buckner’s legs among his favorite moments. Tom Seaver was his favorite player. When Terry Collins let Matt Harvey start the ninth inning in Game 5 of the 2015 World Series, Cohen was there at Citi Field with Alex, bundled up and wearing a new World Series-branded hat.

Multiple childhood friends, though, remember him being more of a Yankees fan. Could both be true?

In the first nine Octobers of Cohen’s life, the Yankees were in the World Series eight times — including five straight from 1960-64 during the formative ages of 4-8. That run that featured two championships. In New York and elsewhere, Mickey Mantle was the man. The Mets didn’t have so much as a winning record until '69, when they, of course, won it all, seemingly solidifying a 13-year-old Cohen’s fandom.

However the early-life rooting interests played out, Cohen was a baseball nut from just about the start and has been loyal to the Mets for decades — so much so that he bought that Buckner ball for $410,000 a few years ago.

"He actually showed it to me when I was at his house once," said Steve Greenberg, the managing director of Allen & Co., a boutique investment bank. "[Buying the one-of-a-kind souvenir] speaks volumes. That predates any involvement in baseball ownership, recognizing the iconic status of that play for New York Mets fans."

Greenberg, a major power broker in this expensive corner of the sports world, is uniquely qualified to speak to Cohen’s baseball obsession as an adult. In 2011-12, when Cohen tried to buy the Dodgers, he hired Greenberg to represent him. This year, Greenberg negotiated the sale of the Mets on behalf of the Wilpon and Katz families, a prolonged process in which he was on the opposite side of the table from Cohen.

"You have to be sharp when you deal with Steve, because he’s not afraid to ask the next question," Greenberg said. "You could be the world’s leading expert and state an opinion, and where others might say, ‘OK, that must be the case,’ he’ll ask, ‘Why is that?’ He likes to get down in the weeds on things that interest him. And baseball clearly interests him.

"When we deal with wealthy people who are interested in buying a sports team, there are a handful who are somewhat agnostic. It could be an NBA team, it could be an NFL team, it could be a baseball team. And some are very sport-specific. And Steve was very sport-specific. This is all about baseball."

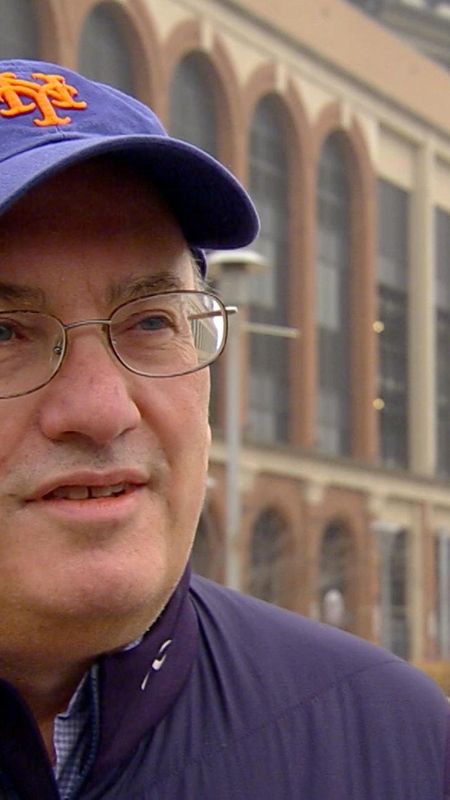

New Mets owner Steve Cohen at Citi Field for a season-ticket holders event on Dec. 12, 2020.

When Cohen was bidding for the Dodgers, he told those around him that he wanted a franchise and he wanted it to be a good business. It wasn’t just a toy. He had no real emotional connection to that team, and he didn’t plan to move his family or business to Los Angeles.

"He didn’t want to be perceived as the wealthy guy who comes in, pays whatever the price is, maybe overpays, loses money and it’s just a vanity play," Greenberg said. "He never was interested in that."

Guggenheim Baseball Management, a group of investors that included Lakers icon Magic Johnson, wound up buying the Dodgers in the spring of 2012 for a price that shocked Cohen: a then-record $2 billion.

He was happy with a minority share of the Mets, which he bought in February 2012, and waited for the chance for more. Seven years later, it came. The more cold-hearted philosophy he would have had with the Dodgers didn’t apply.

"If you buy your hometown team, it’s a very different feeling than buying one [in another city]," Greenberg said. "He understands that whether he makes money or loses money, this is a community trust. Millions of New Yorkers care about how he runs the team."

The Mets sale was classic Cohen. It took nearly a year after the announcement from the club that Cohen, previously unknown to the fan base, was negotiating with the Wilpons and Katzes. But he ended up with everything he wanted, the way he wanted it.

He was tough when he wanted to be, cutting other would-be buyers out of the process by entering exclusive negotiations before the deadline to submit bids. He was gracious to those he knows, never saying a bad public word about the Wilpons. He was wicked smart, shedding the undesirable terms of the initial deal. He was bold enough to flirt with trouble, letting the first arrangement fall apart and staying on the sidelines for months while they looked for new bidders. And he was savvy enough to avoid the worst, jumping back in — and offering the most money, $2.475 billion — when it mattered.

It was as if Cohen was back at the proverbial poker table. This time, though, there was no high-low split. He wanted, and won, the whole pot.

"There was never any wavering," Greenberg said. "He was not really shy about letting us know that. He was pretty straightforward and confident. He was determined to come away with the team."