Bob Arum was ringside. "It was unbelievable," he said.

Thomas Hauser was in the last row of the mezzanine. "It was electric," he said.

Tim Ryan was in a media section just below the blue seats. "There was a buzz," he said.

Tony Paige was in a movie theater in the Bronx. "The vibe, it was just a happening," he said.

So it goes for anyone old enough to recall the first Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier fight, an event that marks its 50th anniversary on March 8 and has retained its luster as one of the most anticipated contests in sports history.

Whether one was inside Madison Square Garden, watching live elsewhere or just following the action via media coverage, there is no forgetting that night and the buildup to it.

That was because this was no mere sports event, even though it had obvious athletic merits, matching a pair of undefeated heavyweights, each with a championship claim.

Beyond that, it got tangled up in the volatile racial, cultural and political dynamics of the era, to the point that for many Americans, the two fighters became proxies for their own positions on issues of the day.

To oversimplify: Anti-Vietnam War liberals, young people and Blacks tended to favor Ali. Conservatives, older people and whites tended to favor Frazier.

"The fight was kind of a symbolic culmination of the divisions and dichotomies of the era around the Vietnam War and the politics of race," said Joseph McLaren, a professor emeritus of English at Hofstra who specializes in African-American, African and Caribbean literature and participated in a 2008 symposium on Ali at Hofstra.

"Ali and Frazier became sort of symbolic representations of those tensions."

The whole, complicated stew threatened to boil over, but by the time fight night came around, many boxing fans and the wider world managed to narrow their focus to the ring itself.

Paige, a former WFAN host and veteran boxing journalist, was a high school senior then. He had paid the princely sum of $25 for a glitchy closed-circuit viewing that lacked both color video and audio of any kind.

"None of that other [political] stuff mattered inside that arena," he said. "Everybody wanted to see a good fight. Nobody was like, ‘Frazier’s an Uncle Tom’ or ‘Ali’s a draft dodger.’ . . . It was just everybody was debating the fight."

There was gambling, there were arguments and there were cheers, mostly for Ali. But Paige recalled it mostly as a spirited community gathering. "It was like a giant barbershop," he said. "That’s the best way to describe it."

Then again, he was only a teenager. Many grown-ups made it more complicated.

Promoters made unbelievable $10 million in profit

The leadup was years in the making. Ali had had his title stripped in 1967 after he refused to serve in the military, citing his religious beliefs as a converted Muslim.

He was denied a license to fight at all from 1967-70, while Frazier secured and consolidated the heavyweight crown by defeating Buster Mathis in 1968 and Jimmy Ellis in ’70.

With the appeal of his conviction for evading the draft still in progress, Ali returned to the ring with warmups against Jerry Quarry and Oscar Bonavena in 1970, leading to the showdown with Frazier.

Arum, who later became a famed promoter, including for Ali-Frazier II in 1974, was working for Ali as an attorney but wanted no part of promoting Ali-Frazier I. He considered the economics to be unworkable.

Jerry Perenchio, a Hollywood impresario, had offered each fighter a guaranteed $2.5 million. He sought to make ends meet by charging the then-outrageous sum of $25 for closed-circuit viewings — and $150 for ringside seats.

Arum knew before the night was over that he had missed a business opportunity.

"I was at the fight getting reports that people in New York were going all over from one [closed-circuit] location to another to get a seat in a location, and they were all sold out," he said.

Perenchio and his partner, Jack Kent Cooke, made a profit of about $10 million, "which was an absurd sum at that time," Arum said.

Ali did his part to generate interest, as always, including by disparaging Frazier for his ability, his appearance and, most cruelly, for being a tool of the white establishment.

It worked. People took sides. Paige may recall a spirit of unity in the Bronx, but in Manhattan and elsewhere, the political tribalism resembled that of recent years.

Ryan, then 31, was shocked by the ill will Ali attracted. "Who would have thought there would be that many people who had those horrible viewpoints?" he said.

The narrative became, as Ryan put it, "the draft dodger versus the workaday, working-class guy who would go in there and throw a million punches. That was Joe — kept his mouth shut and was just kind of the good guy.

"And there was the brash Ali and a lot of people who felt that yeah, he was just a draft-dodger — and Black."

In an essay in Sports Illustrated dated the day of the fight, Mark Kram wrote:

"The disputation of the New Left comes at Frazier with its spongy thinking and push-button passion and seeks to color him white, to denounce him as a capitalist dupe and a Fifth Columnist to the black cause.

"Those on the other fringe, just as blindly rancorous, see in Ali all that is unhealthy in this country, which in essence means all they will not accept from a black man."

Fight became a celebrity magnet

Ryan was working for WPIX-TV at the time and was hired to call the fight for New Zealand radio — one of the few countries allowed to carry live radio because of closed-circuit TV contract rules.

That in turn led to him being heard on Armed Forces Radio Network, because it was one of the few English-language calls available to American service people around the globe.

But the majority of English speakers who followed the fight live outside the arena experienced it through the closed-circuit telecast, with Don Dunphy calling the action beside analysts Archie Moore and . . . Burt Lancaster?

Yup, the actor was a friend of Perenchio, who hired him. Maybe Lancaster just wanted a way to get in the door, as Frank Sinatra did by taking pictures for Life magazine.

Lancaster’s work — available on YouTube — is bizarre and overwrought. Dunphy and especially Moore, a former light heavyweight champion, struggle to get a word in edgewise over his soliloquys.

"It was a ludicrous situation," Ryan said, laughing, of Lancaster’s stylings.

But it was that kind of night, with celebrities such as Miles Davis, Diana Ross, Barbra Streisand, Woody Allen, Sammy Davis Jr., Hugh Hefner, Ted Kennedy, Diane Keaton, Dustin Hoffman and many others in the house.

Ryan recalled a mixture of true fight fans and celebrities and other swells who came merely to be seen.

"They knew who Ali was and they probably knew, some of them, who Joe Frazier was; he was the champion," Ryan said. "But there were people who had never been to a boxing match in their lives. It was an event."

Ryan said he did as much celebrity- watching as anyone. "They’d come in in their ermines and their minks and ballgowns and whatnot," he said. "It was absurd. But that’s why we’re still talking about it 50 years later."

He also recalled some Black fans of Ali’s near the ring dressed so stylishly, "it looked like the Cotton Club days."

"That whole vibe was definitely part of what made this a history-making event," Ryan said.

Gene Tunney, a champion from the 1920s, was in the crowd and introduced by ring announcer Johnny Addie. Then, finally, it was time to begin.

Fighters were polar opposites

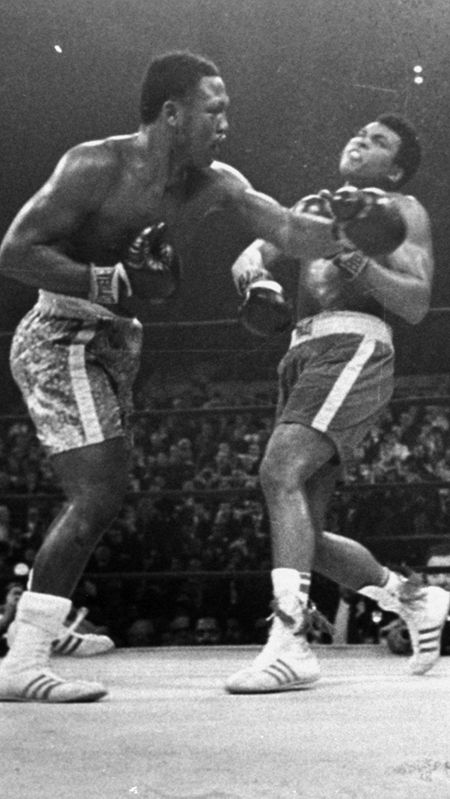

About the bout itself: It was a tough, tight battle, featuring Frazier (26-0), a relentless, bobbing and weaving bull of a fighter, against Ali (31-0), who made his mark in the early 1960s with light feet and quick fists.

There were some comical moments, such as referee Arthur Mercante twice yelling at the yapping fighters to "stop talking!"

Arum recalled the mostly white, mostly well-heeled crowd rooting for Frazier, but more than once, there were chants of "A-li, A-li."

The question for many observers was how Ali’s long layoff would affect him. But Ali’s biggest problem was that Frazier was at the top of his game. After Ali piled up points in the early rounds with effective jabs, he began to tire in the middle rounds and nearly was taken out by Frazier in the 11th.

Frazier was ahead on the cards of both judges and Mercante heading into the 15th and final round, but he made sure of the outcome by dropping Ali to the canvas.

"The crowd, needless to say, is in a bedlam!" Dunphy said. "Muhammad Ali has never taken such a battering!"

Hauser, then 25, had secured a ticket by mailing away for one. He later became Ali’s biographer, notably for the acclaimed 1991 book: "Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times."

He was rooting for Ali and vividly recalls that 15th-round knockdown. "By that point on my very unofficial scorecard, the fight was lost," he said. "I just wanted him to be able to finish on his feet with dignity, which he did."

Said Paige: "Every time Ali landed a punch, the [theater] would go wild, but when Frazier tagged him in the 11th, the crowd was shocked, and when he went down, the crowd was shocked."

McLaren, a recent Queens College graduate at the time, said, "The image of Ali with the swollen jaw was kind of a sign that he had been defeated, and for us, that was a blow. It was definitely a psychological blow, that Ali, who we had put our faith in, had lost."

Layoff or not, Arum said he and his associates "were convinced, all of us, that Ali was unbeatable . . . I thought it was a fait accompli that Ali would roll over Frazier."

Then he didn’t. "I was shocked," Arum said.

Ali publicly took issue with the decision that night, and three years later, while promoting Ali-Frazier II, he still was calling it a racially and politically motivated ruling.

But Hauser said that long after the fact as he watched video of that fight and others with Ali, the former champ did not deny that he had been outfought.

"He accepted the fact that he lost, that he fairly lost it on the judges’ scorecards," Hauser said. "He saw things that he could have done differently and better and it sort of fit within the warm memories of his life.

"When we look back on our lives, we can have warm memories of some of the things that went against us."

Epilogue

Ali and Frazier met twice more, in 1974 and ’75, with Ali winning both.

Hauser said of the three bouts with a claim as the 1900s’ "Fight of the Century" — along with Jack Johnson over James Jeffries in 1910 and Joe Louis over Max Schmeling in 1938 — Ali-Frazier was the only one whose outcome was secondary.

"Frazier won the first Ali-Frazier fight, and yet in the tide of history, if you will, that seems to have become fairly unimportant," Hauser said.

As the decades passed, Ali’s early image as a radical provocateur softened, and by the time he died in 2016, he was a beloved and admired figure. Frazier, who died in 2011, became something of a historical footnote.

But on that night in 1971, the two entered the ring as sporting equals and fashioned an indelible moment.

"I left the Garden that night feeling sad that [Ali] had lost," Hauser said, "but knowing that I had witnessed something historic both as a great fight and also as an important social and political event."

Arum, 89, who has been to many hugely hyped and far more lucrative fights in the decades since, recalled the "electric" Garden of that occasion and said that bout remains at the top of his personal list.

"If you ask my instinct and my feeling, but not something you can measure with actual data, I would say yes," Arum said. "The whole world appeared to stop . . . I’ll never forget it.

"I know exactly where I was sitting. I know exactly what I was feeling. How many events that you have been to can you remember that?"

Ali-Frazier II, Jan. 28, 1974, Madison Square Garden

By the time Muhammad Ali got another shot at Joe Frazier, nearly three years had passed, and Frazier had lost his belt to George Foreman, making this a non-title fight. Ali avenged his ‘71 loss, earning a 12-round unanimous decision despite being criticized for frequent clinches. Days before the fight, the two scuffled on the set of ABC’s “Wide World of Sports” while watching their 1971 fight with Howard Cosell, after Ali called Frazier “ignorant” and Frazier confronted him.

Ali-Frazier III, Oct. 1, 1975, Araneta Coliseum, Quezon City, Philippines

“The Thrilla in Manila” is regarded as one of the most bruising heavyweight battles of all time. Ali retained his championship when Frazier did not come out for the 15th round, at the insistence of trainer Eddie Futch. By that time, Ali was considering quitting the match himself, having absorbed a beating from Frazier, who attacked as Ali used his defensive, “rope-a-dope” approach. But with Frazier’s vision impaired, Ali eventually took charge and won — at great physical cost.

— NEIL BEST