Feminist history was made at SUNY Old Westbury.

It was there, from 1971 to 1985, that the publishing company the Feminist Press reintroduced out-of-print books by female writers such as Zora Neale Hurston and helped to launch feminist works by activists like Barbara Ehrenreich. Under the leadership of professor Florence Howe, the Press, which still exists, helped advance the nascent movement to teach women’s studies and brought to light some of the writings that are now key to the field.

Howe was part of a collective endeavor among the Old Westbury faculty, who developed women’s studies courses at the college and a concentration, which became a minor in 1998. In 2023, the college started offering it as a major.

“Florence’s lasting impact was the Feminist Press, the importance of feminist writings, the voice of women in understanding all aspects of world culture and society and the fact that we still use the books to teach today,” said Laura Anker, who joined the college’s American Studies department in 1978 and was Howe’s colleague. “Florence and the Press also had an enormous influence on Old Westbury and the academic world. … By the time Florence left [in 1985], courses focusing on women were part of the curriculum of most departments at the college, interdisciplinary and disciplinary. This was an enormous change.”

BIRTH OF THE FEMINIST PRESS

In her 2011 memoir, “A Life in Motion,” Howe — who died in 2020 — wrote that in 1970, she was teaching women’s studies at Goucher College in Maryland and had begun a “clearinghouse on women’s studies” to document courses across the country. She wanted to produce a series of books written by contemporary women to address a gender gap in the texts being taught in schools. Traditional academic presses weren’t interested. Undeterred, Howe credited her partner at the time, Paul Lauter, with the idea to publish the books themselves and to call the new endeavor the Feminist Press.

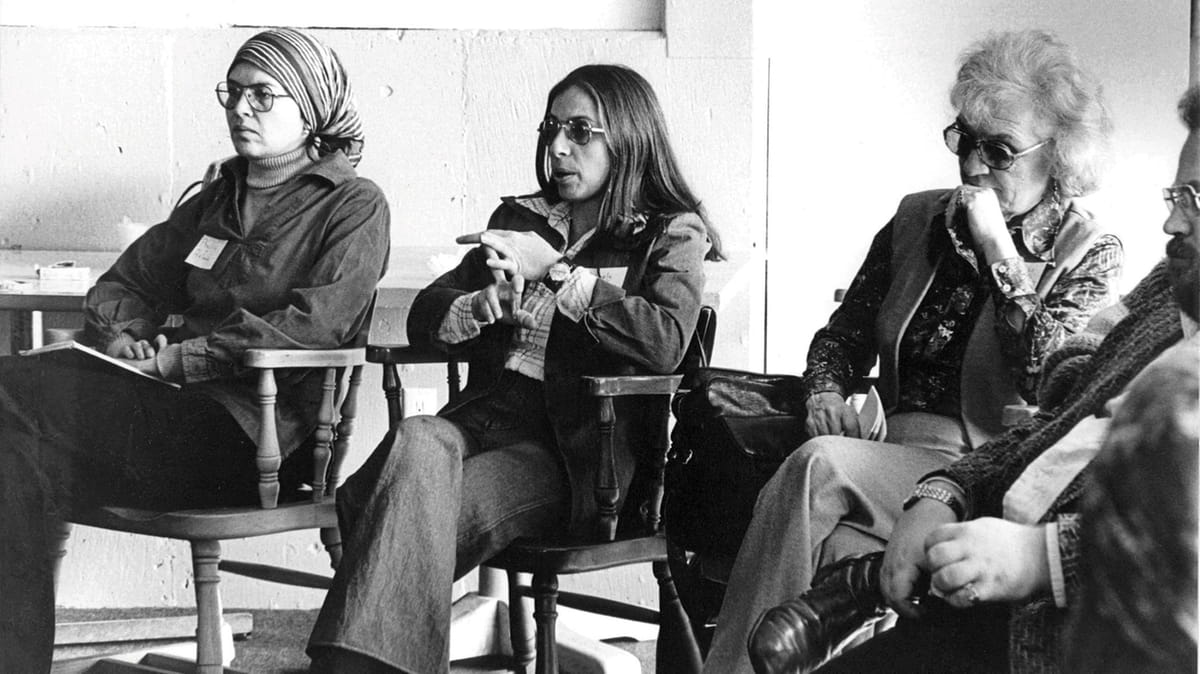

Florence Howe of the Feminist Press. Credit: SUNY Old Westbury Library Archive

At first Howe ran it out of their home in Baltimore. But in 1971, she was offered a full-time position at nearly twice her salary at what was then known as the College at Old Westbury, which had started with a class of 85 students just three years earlier.

Tasked with helping to create a women’s studies program within American Studies, Howe arrived with the understanding that the college would provide her with resources to continue the publishing company and the clearinghouse, according to her 1972 annual report to the college president.

Anker, 78, who retired in 2022 as a distinguished service professor and until recently lived in East Hampton, said the presence of Howe and the Press in the 1970s reflected Old Westbury’s commitment to an inclusive, interdisciplinary curriculum and student body. Carol Quirke, co-director of Experiments: Old Westbury Oral History Project, a digital history of the college’s early years, said the school was conceptualized to enroll nontraditional students and those who had been historically bypassed: students of color, working-class students and women, particularly those returning to college.

Carol Quirke, professor of American Studies, stands in the footprint of the Feminist Press building at SUNY Old Westbury. Credit: Jeff Bachner

“The college was very much a center of innovation and, in some ways, radicalism in the 1960s and 1970s, so I think that’s how Florence Howe ended up at Old Westbury,” said Quirke, a professor of American Studies.

Even so, Howe’s arrival reflected the very issues feminists were struggling against at the time. She wrote in her book that when she got there in the fall of 1971, a guard at the gatehouse asked her, “And whose secretary are you?” When she said she was a professor, he called the president’s office for confirmation.

Naomi Rosenthal, 83, of East Setauket, was hired in 1975 as a member of the American Studies faculty. “I think it’s hard for people to recognize how much change has happened, not just that there are women’s studies degrees, but how much knowledge we have about women. … It took the pioneering folks like Florence, who may have been the midwife of women’s studies at Old Westbury, to make that happen,” said Rosenthal, who retired from the university in 2003.

Naomi Rosenthal at her home in East Setauket. Credit: Barry Sloan

WOMEN’S STUDIES FACULTY

Howe was one of eight female faculty who taught an introductory course in women’s studies. Other professors included Ehrenreich and Rosalyn Baxandall, both of whom would go on to have careers as prominent authors and feminist activists.

In addition to teaching, Howe was running the Press. She would later describe the organization as “creative chaos” as she was chief grant proposal writer, a professor and the person responsible for the funds. Lauter, now 91 and living in Leonia, New Jersey, was the treasurer. He said at first they published just three kinds of books: reprints, children’s books and biographies of women. Much of Howe’s time was involved in fundraising, since she said she arrived on campus without capital for the Press.

Initially, the Press was in her academic office. But in 1975, she was offered what she called “the little brown house,” a former day care center.

According to Lauter, “It provided a kind of a home for all of the staff there that was not right in the middle of a college. It allowed for the building of staff morale, which was very good because the process of developing a small indie press was very demanding, and we did a lot of the work ourselves.”

That staff included women from what Howe called an on-campus internship “that involved students in every aspect of publishing from editing through shipping book orders.” There were also about five paid staff members, mostly women who were returning to work. Among them was Shirley Frank, who said she started at the Press in 1977 on the reprints committee.

“When I got this job, I thought this is a wonderful thing to be able to produce these works that are going to change the world. We were really trying to change education on every level, including women’s studies in universities,” said Frank, now 80, who lives in Manhattan.

Feminist Press staff members Phylis Arlow, Merle Froschl and Sophie Zimmerman at a journalism conference at SUNY Old Westbury in February 1976. Credit: SUNY Old Westbury Library Archive

Among the first books Howe highlighted — with the input of activist and author Tillie Olsen — was the novella “Life in the Iron Mills.” Written by Rebecca Harding Davis, it was originally published anonymously in 1861 and established social class as a major issue in women’s lives. Howe also published Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” a short story written in 1892 about postpartum depression. In 1973, the Press reprinted Hurston’s out-of-print book “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” as well as her anthology, “I Love Myself When I Am Laughing … and Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive,” which was edited by Alice Walker, who would later write “The Color Purple.”

In addition to publishing older works, the Press also sought to provide a platform for contemporary writers. Among them was Ehrenreich, whose pamphlet on medical establishment corruption, “Witches, Midwives & Nurses: A History of Women Healers,” co-authored with the future editor of Mother Jones magazine, Deirdre English, was published by the Press in 1973. It is still sold today.

By 1975, with a backlist of 30 books, Howe’s efforts had also grown to a wide range of educational activities “offering alternatives to sexual stereotypes in books and curriculum.” She designed curriculum and spoke at colleges and universities around the world.

The Press also created “Women’s Studies Quarterly,” a peer-reviewed interdisciplinary journal that is still published twice a year; bibliographies like “Feminist Resources for Schools and Colleges: A Guide to Curriculum Materials;” and a directory of “Who’s Who and Where in Women’s Studies,” a comprehensive listing of women’s studies courses and faculty at colleges across the country.

In 1974, the Press held a national conference on women’s studies. The Dec. 17, 1974, issue of “The Catalyst” said it was covered by members of the local and national press, including The New York Times, Newsday and Ms. Magazine, as “an important landmark in the career of nonsexist consciousness in the U.S.”

A NONCONFORMING WORKPLACE

Frank said all of this took place in an atypical workplace.

“I remember a meeting when one woman started to cry because she was in the middle of getting a divorce,” Frank said. “Florence asked her if she wanted to talk about it. I don’t think those things would’ve happened in an organization run by men.”

Sally Smith was 36 in 1981 when Howe hired her to work on an annotated bibliography of recommended fiction for children ages 10-14. Called Project Equal, it was funded by The Rockefeller Foundation and managed by Howe in conjunction with the New York Board of Education. Three days a week Smith worked at Old Westbury.

We’re the only real feminist press in the world now. We are still moving along. It’s very exciting to be part of it.

-Helene Goldfarb

“The Press was an interesting place to work and so informal that the copy machine was in the bathroom,” said Smith, 80, of Brooklyn. “We sat at a table in a big room and everyone was working on different projects. Some were doing more secretarial-type work. Others were working on other book publishing projects.”

Helene Goldfarb, then in her 50s and teaching in New Rochelle, began volunteering at the Press in 1982 after she bumped into Howe at the Bonwit Teller department store in Manhasset. Howe had been her sorority sister at Hunter College in the 1940s.

Now 94 and living in Manhattan, Goldfarb is the Press’ vice chair and president emerita of the board of trustees. Recalling those early days, she said, “At that time, [the Press] didn’t have a board of directors. ... It was almost like a commune. Everybody volunteered except the five or six people ... who were there seriously because she didn’t have the money to pay people.”

GROWING PAINS

That question of salary soon became contentious. Frank, a divorced mother at the time, said everyone was paid the same amount, whether their job was editing or packing books: $11,000 a year. “For some people, that was nice. For me, it was really tough because I was trying to live on it. And then paychecks were bouncing,” said Frank, who left in 1983 to take an editing job but later freelanced for the Press.

Howe also drew that amount, which led to a dispute in 1980 with staffers who questioned her taking a salary both as a professor and as a Press staff member. Just after the organization’s 10th anniversary, this led to the walkout of eight staffers. Kitty Stewart, who had graduated from Old Westbury that year with a degree in American Studies at age 33, was offered a job at the Press when she ran into Lauter, who had been her professor.

Florence Howe, bottom left, with staffers of the Feminist Press in 1982. They are, clockwise from top left: Shirley Frank, Heera Veeravaga, Constance Green, Jane Williamson and Vina Mazumdar. Credit: SUNY Old Westbury Library Archive

“It was sort of pandemonium when I got there,” recalled Stewart, 76, of Glen Cove. “Some of those people still wanted their job, but Florence wanted them out because they had walked out. So none of the orders had been fulfilled. They put me in charge of fulfillment.”

Stewart said she worked there for three years with a starting salary of $12,000. “When I first got there, they had nice things like personal days to sort of make up for the salary. It drew interesting, good people, and I thought I was doing important work. But after a while, stuff just started getting crazy. You never knew what was going to happen with Florence — like, you had a benefit and then one day she would decide it didn’t exist. I was working late one night so I could take a personal day, and she just took it away.”

So Stewart helped to organize a union in 1983. The women won, but because she had been a leader, she was told she couldn’t be part of the union. She left that year, becoming an editor for a number of different publishers.

Lauter, who said he was impacted professionally for standing by Howe during the union dispute, said she could be “extremely controlling.” The two broke up in 1982.

Even before the unionization effort, Howe’s relationship with some of the staff and the university was changing, according to Lauter. On Sunday, Sept. 19, 1982, a fire broke out around 7:50 p.m. in the Press office. The building was empty and, according to an article in “The Catalyst,” the fire took two hours to contain.

The blaze was classified as an accidental electrical fire. But both Howe and Goldfarb were convinced it was set, with Goldfarb blaming people opposed to women’s rights.

“We were a feminist group. We had a name of the Feminist Press,” said Goldfarb. “They didn’t want us there.”

By the fall of 1985, when the vice chancellor of CUNY asked Howe if she would like to move the publishing house to Hunter College in Manhattan, she agreed. She wrote that it wasn’t until she was at CUNY that she finally learned to run a publishing company.

Goldfarb said the situation worked out well. “By that time we were better staffed, we had a board of directors and bylaws. It became much more of a structured business.”

HOWE’S LEGACY

Despite its controversies, Howe and the Feminist Press made significant contributions to the field of women’s studies and publishing, said Rosenthal, a visiting professor in the sociology department at Stony Brook University. “It was a very important enterprise," she said. "This was the very beginning of publishing in the area of women’s studies, and they were among the first to provide books that were of use not only for courses that wanted to focus on women’s studies, but also for women who were part of the feminist movement."

Members of SUNY Old Westbury’s Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies program, including Carol Quirke, center, at the footprint of the Feminist Press’building with some of the publisher’s books. Credit: Jeff Bachner

Goldfarb said that 54 years after Howe started the Feminist Press, it remains a nonprofit, publishing female writers from all over the world. Current editorial initiatives include the Louise Meriwether First Book Prize, created to highlight debut work by women and nonbinary writers of color, and Amethyst Editions, a queer imprint founded by Michelle Tea.

“I think Florence’s legacy was having the guts to do this, and that people are still interested,” Goldfarb said. “We’re the only real feminist press in the world now. We are still moving along. It’s very exciting to be part of it.”

The Feminist Press Book Club

Another legacy of The Feminist Press days in Old Westbury is the book group that formed in 1983 around the office kitchen table. Kitty Stewart said it continues with about seven original members, including Naomi Rosenthal, Shirley Frank and Sally Smith.

“Florence (Howe) came to our first one,” she said. “We realized that we were all at the Press because we were all readers and liked books, but we never had the chance to talk about books when we were at work. So we decided to have a book club to read feminist books after work. We’ve been meeting ever since."

— Liza Burby