A Wyandanch family lived without heat for months. Their landlord now faces a criminal charge.

Xiomara Mejia’s house is warm again, after a monthslong battle with her landlord and a journey through a maze of Long Island red tape.

While her family celebrates having heat in their Wyandanch home, her landlord, Yared Samuel, is facing a criminal charge of unlawful eviction, a misdemeanor, Suffolk County police said. An investigation determined that the oil burner in her home had been shut off in December, police said. Under state law, it would be a crime to shut off heat in order to drive out tenants, housing attorneys said.

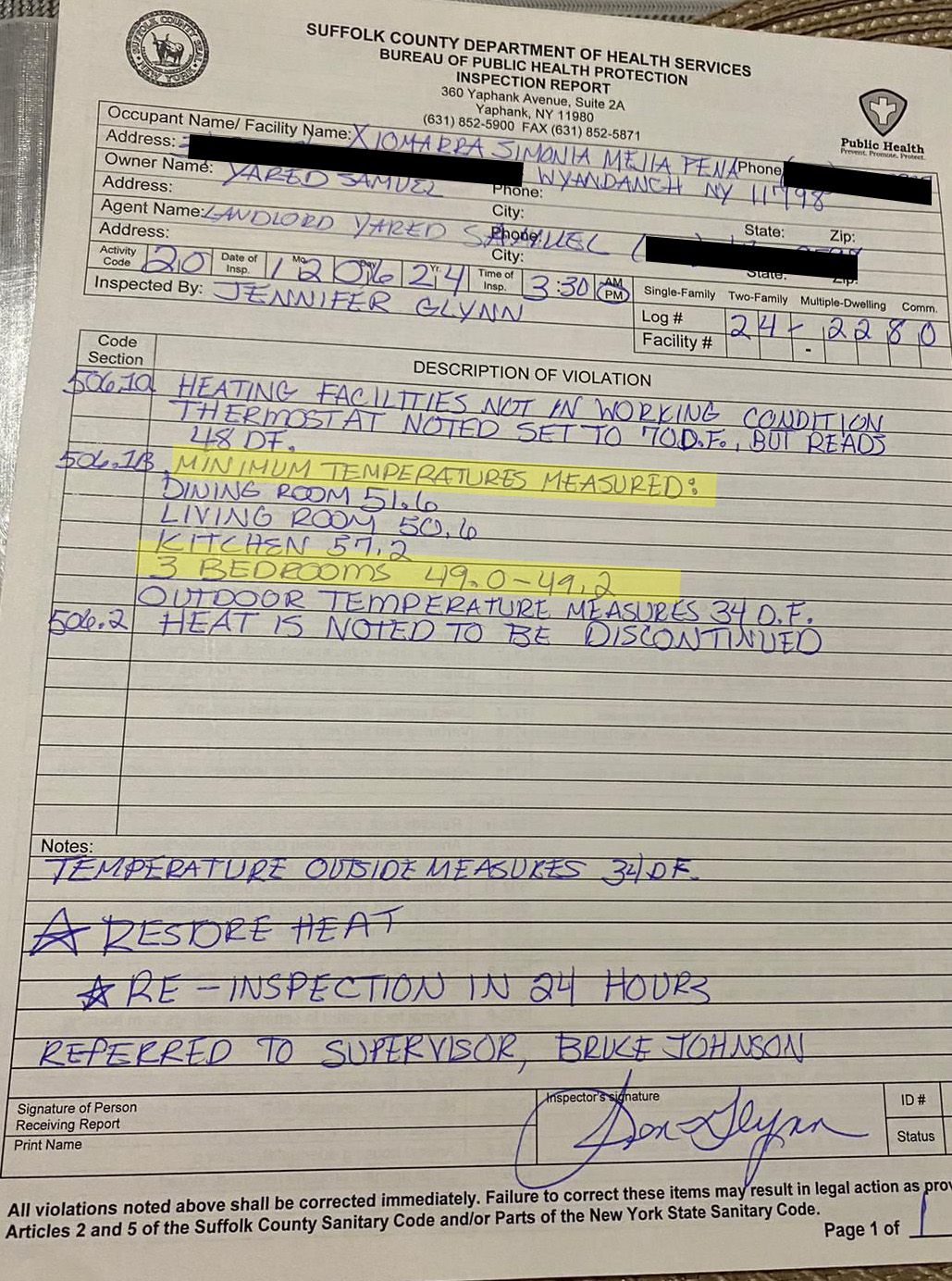

The lack of heat left Mejia’s family of five sleeping near their two space heaters as wind chills made the temperature outside feel like single digits. Daytime temperatures inside the home dipped as low as 49 degrees, county health inspectors’ reports show.

"It's been tough, probably like the worst Christmas or the worst New Year's that we've ever had," said Mejia’s son Saul Antonio Paz Mejia, 17, a senior at Central Islip Senior High School who plans to study engineering in college. Except for sleeping, he said, "we didn't spend that much time in the house."

It took from October until January to restore service, other than a nine-day period in mid-December, county records show.

The difficulties faced by Mejia and her family — husband Saul Paz Garcia, son Saul Antonio and two daughters, ages 16 and 21 — highlight hardships renters can encounter despite New York’s strong tenant protections, housing advocates said. Restoring heat to Mejia’s home involved social workers, nonprofit housing counselors and attorneys, Town of Babylon code enforcement and Suffolk County health officials, police and a state district court judge.

The situation remained largely unresolved for months, until Newsday made calls to officials in January, said Ian Wilder, executive director of the nonprofit Long Island Housing Services in Bohemia, which advocated for the family.

Newsday first inquired about the case on Jan. 6. Mejia said the heat was restored Jan. 10. Suffolk police charged Samuel with unlawful eviction on Jan. 14.

"We are very pleased that action has finally been taken," Wilder said. But the case demonstrates "systemic failure" by police and other government officials, he said.

The Suffolk Police Department is reissuing a training memorandum to officers about state law on illegal evictions, police spokeswoman Dawn Schob said in an email.

The police investigation into Mejia's situation showed her landlord was responsible for delivery of heating oil and maintaining the oil burner, and tenants were responsible for "all utilities except oil," Schob said. Samuel is due in district court in Central Islip in February, police said.

In a phone interview Jan. 9, before heat was restored, Samuel said the tenants were responsible for paying for heat, and they were months behind. Samuel filed a civil eviction case on Dec. 2, court records show.

"We’re trying to fix the heat," he had told Newsday. "We're going through the proper system [to get a court order to evict them] ... but we're still doing everything that we can to help them out." He referred further questions to his attorney in the civil eviction case, Glenn Nugent, who is based in Amityville.

Nugent said on Jan. 14 that his client had been acting lawfully. "The parties in good faith agreed to resolve" the civil eviction case, he said. Of Samuel, he said, "He’s got his own financial issues."

Nugent said he was not representing Samuel in the criminal case, did not know if Samuel had retained an attorney for the case and could not comment about the charge.

Approached at the courthouse on Jan. 14, Samuel declined Newsday's request for comment.

Mejia’s family moved into the three-bedroom house in June.

The home lost hot water in August, forcing the family to boil water to bathe themselves, she said. The situation was especially stressful for their daughters, since the 16-year-old has autism and the 21-year-old has disabilities due to a brain tumor, said Mejia, who works as a food delivery app driver. Garcia, her husband, drives a delivery truck.

On Sept. 12, the family filed a complaint with the Town of Babylon and officials advised them to contact the county health department and Long Island Housing Services. The town gave the landlord a summons for lacking a rental permit.

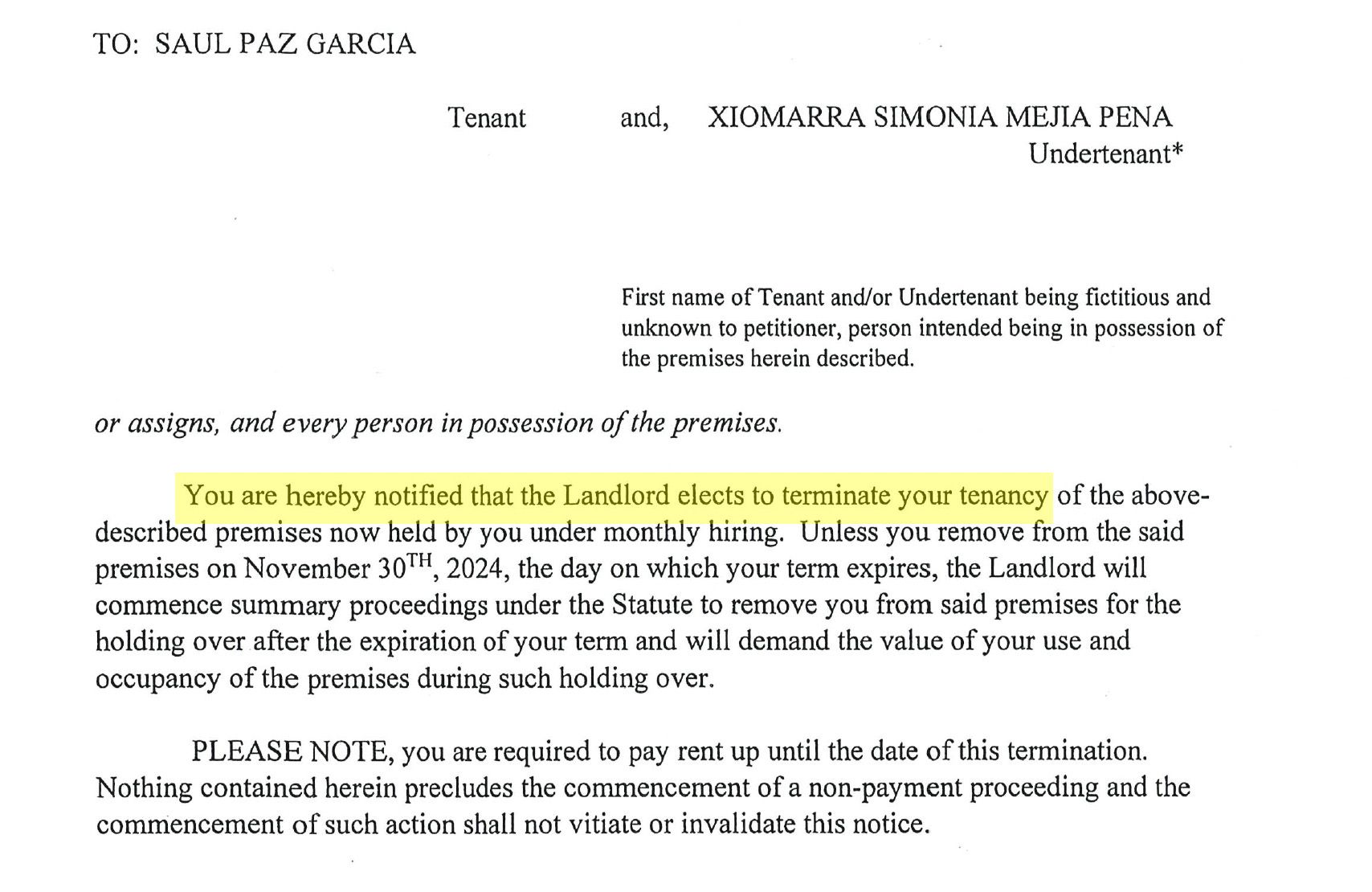

Samuel sent Mejia and her husband an eviction notice dated Oct. 1. Later that month, the family started complaining to Suffolk police, records show.

On Oct. 14, a police officer came to the house and told them they should call when the landlord was home. Two weeks later, they called police when the landlord visited the house, but by the time the officer arrived the landlord had left. The next day, a police officer "spoke with the landlord, and the landlord told him that he needed a part, and that was the reason the heating system was not working, and he had to empty the oil tank," Mejia and Garcia said in court papers.

The couple called that an "excuse" in court papers and wrote, "The police officer suggested we bring the landlord to court."

They stopped paying rent in November, and early the next month Samuel filed the eviction case in court.

The state's new Tenant Dignity and Safe Housing Act, which took effect last year, gives renters the right to sue landlords over unsafe conditions, but excludes Nassau and Suffolk counties. Lawmakers left out Long Island because some legislative staffers worried that a technical element of it — having to do with Long Island’s unusual district courts — might violate the state constitution, according to a representative for one of the bill’s sponsors.

Without the protections of the new law, Long Island tenants who lose heat have little recourse but to stop paying rent and wait for the landlord to file an eviction case, said A.J. Durwin, a managing attorney with the Empire Justice Center. That allows them to ask a judge for help, he said.

Landlords "cannot discontinue essential services such as heat or electricity or hot water" to force renters out, Durwin said.

From October through early January, the family called police at least six times, Mejia and Garcia said in a sworn affidavit they filed in the civil eviction case. But Suffolk police "did very little to compel the landlord to restore the heat," the couple said.

On Nov. 1, the family called police, but the officer did not ask Samuel to turn on the heat and hot water, Mejia and Garcia said in their affidavit. In early December, an officer went to Samuel's address but "found that this was the landlord's brother's address," the couple said. The officer contacted the county health department and an inspector visited the home, they said.

Heat and hot water were restored Dec. 8, but the heat went out again Dec. 17, records show.

From Dec. 6 through Jan. 9, county health inspectors visited at least nine times. They recorded inside temperatures as low as 49 degrees, referred the case to supervisors and repeatedly ordered next-day re-inspections, reports show.

The family called police on Jan. 7, but the officer told them "nothing could be done and we had to go to court," the couple said in their affidavit. At the Jan. 14 court hearing on the civil eviction case in Second District Court in Lindenhurst, Samuel agreed to maintain heat and hot water and waive the $2,100 monthly rent from November on, if the family moves out by Feb. 28. Judge Kenneth Lauri approved the settlement.

"We are very happy, to be honest, because they were charging us a bit over $5,100," Mejia said in Spanish. "We were afraid because we don’t have that amount. But thank God it was in our favor."

Statewide, city and district courts issued more than 33,700 civil eviction orders last year, including 2,634 in Nassau and 4,304 in Suffolk, state court figures show. The numbers do not include courts in towns, villages or New York City.

In the five-year period ending in 2024, there were 36 cases in Suffolk County, 17 in Nassau and 117 statewide, excluding New York City, in which landlords faced criminal charges of unlawful eviction, a Newsday analysis of court data shows. The analysis included cases in which unlawful eviction was the top charge.

Suffolk police said its officers handled 55 allegedly illegal evictions last year and made 11 arrests. Officers are trained to make referrals to landlord-tenant court and mediation services, authorities said.

The state's Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act, passed in 2019, makes it a crime to shut off essential services if it’s intended to force tenants out, housing attorneys said. A 2022 memo from state Attorney General Letitia James urged police to treat such cases as crimes rather than civil landlord-tenant disputes.

However, police rarely use that law to charge landlords or compel them to restore utilities, according to tenant advocates and landlord representatives.

It’s "very rare" for landlords to face criminal charges for illegal evictions, said Andrew Lieb, a Smithtown-based real estate attorney. "There are typically conflicting allegations of who is responsible and it's a matter that needs to be determined" in court, he said in an email.

Paul Palmieri, a former landlord and president of the Coalition of Landlords, Homeowners and Merchants in Lindenhurst, said when he gets calls from landlords who want to evict tenants, he tells them to go to court.

"You can’t just take the law into your own hands," he said, "and that’s what a lot of landlords have done."

Mejia remains troubled it took so long to get help.

"Many families are going through similar or worse things than me," she said in Spanish. "Sometimes they're afraid of retaliation, and they don't talk."

That wasn't an option for her, she said: "To see my children, the three of them, suffering without heat and nobody listening to us, I was very angry."

With Belisa Morillo and Arielle Martinez

Xiomara Mejia’s house is warm again, after a monthslong battle with her landlord and a journey through a maze of Long Island red tape.

While her family celebrates having heat in their Wyandanch home, her landlord, Yared Samuel, is facing a criminal charge of unlawful eviction, a misdemeanor, Suffolk County police said. An investigation determined that the oil burner in her home had been shut off in December, police said. Under state law, it would be a crime to shut off heat in order to drive out tenants, housing attorneys said.

The lack of heat left Mejia’s family of five sleeping near their two space heaters as wind chills made the temperature outside feel like single digits. Daytime temperatures inside the home dipped as low as 49 degrees, county health inspectors’ reports show.

"It's been tough, probably like the worst Christmas or the worst New Year's that we've ever had," said Mejia’s son Saul Antonio Paz Mejia, 17, a senior at Central Islip Senior High School who plans to study engineering in college. Except for sleeping, he said, "we didn't spend that much time in the house."

WHAT NEWSDAY FOUND

- A Wyandanch family spent months complaining about lack of heat in their home, with little action.

- It's a crime to shut off heat in an effort to force tenants out, housing attorneys said.

- The family's landlord now faces a rare criminal charge of unlawful eviction.

It took from October until January to restore service, other than a nine-day period in mid-December, county records show.

The difficulties faced by Mejia and her family — husband Saul Paz Garcia, son Saul Antonio and two daughters, ages 16 and 21 — highlight hardships renters can encounter despite New York’s strong tenant protections, housing advocates said. Restoring heat to Mejia’s home involved social workers, nonprofit housing counselors and attorneys, Town of Babylon code enforcement and Suffolk County health officials, police and a state district court judge.

The situation remained largely unresolved for months, until Newsday made calls to officials in January, said Ian Wilder, executive director of the nonprofit Long Island Housing Services in Bohemia, which advocated for the family.

The home the Mejia family rents in Wyandanch. Credit: Newsday/ Alejandra Villa Loarca

Newsday first inquired about the case on Jan. 6. Mejia said the heat was restored Jan. 10. Suffolk police charged Samuel with unlawful eviction on Jan. 14.

"We are very pleased that action has finally been taken," Wilder said. But the case demonstrates "systemic failure" by police and other government officials, he said.

The Suffolk Police Department is reissuing a training memorandum to officers about state law on illegal evictions, police spokeswoman Dawn Schob said in an email.

The police investigation into Mejia's situation showed her landlord was responsible for delivery of heating oil and maintaining the oil burner, and tenants were responsible for "all utilities except oil," Schob said. Samuel is due in district court in Central Islip in February, police said.

In a phone interview Jan. 9, before heat was restored, Samuel said the tenants were responsible for paying for heat, and they were months behind. Samuel filed a civil eviction case on Dec. 2, court records show.

"We’re trying to fix the heat," he had told Newsday. "We're going through the proper system [to get a court order to evict them] ... but we're still doing everything that we can to help them out." He referred further questions to his attorney in the civil eviction case, Glenn Nugent, who is based in Amityville.

Nugent said on Jan. 14 that his client had been acting lawfully. "The parties in good faith agreed to resolve" the civil eviction case, he said. Of Samuel, he said, "He’s got his own financial issues."

Nugent said he was not representing Samuel in the criminal case, did not know if Samuel had retained an attorney for the case and could not comment about the charge.

Approached at the courthouse on Jan. 14, Samuel declined Newsday's request for comment.

Numerous complaints

Xiomara Mejia at home. After they lost hot water, the family was forced to boil water to bathe, she said. Credit: Newsday/ Alejandra Villa Loarca

Mejia’s family moved into the three-bedroom house in June.

The home lost hot water in August, forcing the family to boil water to bathe themselves, she said. The situation was especially stressful for their daughters, since the 16-year-old has autism and the 21-year-old has disabilities due to a brain tumor, said Mejia, who works as a food delivery app driver. Garcia, her husband, drives a delivery truck.

On Sept. 12, the family filed a complaint with the Town of Babylon and officials advised them to contact the county health department and Long Island Housing Services. The town gave the landlord a summons for lacking a rental permit.

Samuel sent Mejia and her husband an eviction notice dated Oct. 1. Later that month, the family started complaining to Suffolk police, records show.

The family received this eviction notice in October. Xiomara's name is misspelled in the document.

On Oct. 14, a police officer came to the house and told them they should call when the landlord was home. Two weeks later, they called police when the landlord visited the house, but by the time the officer arrived the landlord had left. The next day, a police officer "spoke with the landlord, and the landlord told him that he needed a part, and that was the reason the heating system was not working, and he had to empty the oil tank," Mejia and Garcia said in court papers.

The couple called that an "excuse" in court papers and wrote, "The police officer suggested we bring the landlord to court."

They stopped paying rent in November, and early the next month Samuel filed the eviction case in court.

LI excluded from law

The state's new Tenant Dignity and Safe Housing Act, which took effect last year, gives renters the right to sue landlords over unsafe conditions, but excludes Nassau and Suffolk counties. Lawmakers left out Long Island because some legislative staffers worried that a technical element of it — having to do with Long Island’s unusual district courts — might violate the state constitution, according to a representative for one of the bill’s sponsors.

Without the protections of the new law, Long Island tenants who lose heat have little recourse but to stop paying rent and wait for the landlord to file an eviction case, said A.J. Durwin, a managing attorney with the Empire Justice Center. That allows them to ask a judge for help, he said.

Landlords "cannot discontinue essential services such as heat or electricity or hot water" to force renters out, Durwin said.

From October through early January, the family called police at least six times, Mejia and Garcia said in a sworn affidavit they filed in the civil eviction case. But Suffolk police "did very little to compel the landlord to restore the heat," the couple said.

On Nov. 1, the family called police, but the officer did not ask Samuel to turn on the heat and hot water, Mejia and Garcia said in their affidavit. In early December, an officer went to Samuel's address but "found that this was the landlord's brother's address," the couple said. The officer contacted the county health department and an inspector visited the home, they said.

Heat and hot water were restored Dec. 8, but the heat went out again Dec. 17, records show.

From Dec. 6 through Jan. 9, county health inspectors visited at least nine times. They recorded inside temperatures as low as 49 degrees, referred the case to supervisors and repeatedly ordered next-day re-inspections, reports show.

The Suffolk County health inspection on Dec. 6 noted temperatures in the bedrooms dropped to 49 degrees. Xiomara's name is misspelled in the document.

The family called police on Jan. 7, but the officer told them "nothing could be done and we had to go to court," the couple said in their affidavit. At the Jan. 14 court hearing on the civil eviction case in Second District Court in Lindenhurst, Samuel agreed to maintain heat and hot water and waive the $2,100 monthly rent from November on, if the family moves out by Feb. 28. Judge Kenneth Lauri approved the settlement.

"We are very happy, to be honest, because they were charging us a bit over $5,100," Mejia said in Spanish. "We were afraid because we don’t have that amount. But thank God it was in our favor."

'Very rare' criminal charge

Statewide, city and district courts issued more than 33,700 civil eviction orders last year, including 2,634 in Nassau and 4,304 in Suffolk, state court figures show. The numbers do not include courts in towns, villages or New York City.

In the five-year period ending in 2024, there were 36 cases in Suffolk County, 17 in Nassau and 117 statewide, excluding New York City, in which landlords faced criminal charges of unlawful eviction, a Newsday analysis of court data shows. The analysis included cases in which unlawful eviction was the top charge.

Suffolk police said its officers handled 55 allegedly illegal evictions last year and made 11 arrests. Officers are trained to make referrals to landlord-tenant court and mediation services, authorities said.

The state's Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act, passed in 2019, makes it a crime to shut off essential services if it’s intended to force tenants out, housing attorneys said. A 2022 memo from state Attorney General Letitia James urged police to treat such cases as crimes rather than civil landlord-tenant disputes.

However, police rarely use that law to charge landlords or compel them to restore utilities, according to tenant advocates and landlord representatives.

It’s "very rare" for landlords to face criminal charges for illegal evictions, said Andrew Lieb, a Smithtown-based real estate attorney. "There are typically conflicting allegations of who is responsible and it's a matter that needs to be determined" in court, he said in an email.

Paul Palmieri, a former landlord and president of the Coalition of Landlords, Homeowners and Merchants in Lindenhurst, said when he gets calls from landlords who want to evict tenants, he tells them to go to court.

"You can’t just take the law into your own hands," he said, "and that’s what a lot of landlords have done."

Mejia remains troubled it took so long to get help.

"Many families are going through similar or worse things than me," she said in Spanish. "Sometimes they're afraid of retaliation, and they don't talk."

That wasn't an option for her, she said: "To see my children, the three of them, suffering without heat and nobody listening to us, I was very angry."

With Belisa Morillo and Arielle Martinez

Police response

In a sworn affidavit they filed in the civil eviction case, Xiomara Mejia and Saul Paz Garcia said they called police at least six times. They gave this account of the police response:

Oct. 14: An officer "advised me that I must call the police when the landlord was at home, so they could speak with him and pressure him to turn on hot water and heating services."

Oct. 28: The family called police when the landlord was at the house, but when the officer arrived, "the landlord had already left."

Oct. 29: A police officer spoke with the landlord, who told them he needed a part for the boiler. The officer "suggested we bring the landlord to court."

Nov. 1: The officer "did not do anything and did not even ask the landlord to put the hot water and the heat on."

Dec. 4: A police officer "who was kind to us" went to the landlord's address, but "found out that this was the landlord's brother's address." The officer contacted the county health department, which sent an inspector.

Jan. 7: A police officer "advised me that nothing could be done and we had to go to court."

Source: Jan. 13 sworn affidavit by Saul Paz Garcia and Xiomara Mejia

This is a modal window.

Shinnecock travel plaza fight ... Fitness Fix: Fluid Power Barre ... St. John's tourney send off ... Get the latest news and more great videos at NewsdayTV

This is a modal window.

Shinnecock travel plaza fight ... Fitness Fix: Fluid Power Barre ... St. John's tourney send off ... Get the latest news and more great videos at NewsdayTV

Most Popular